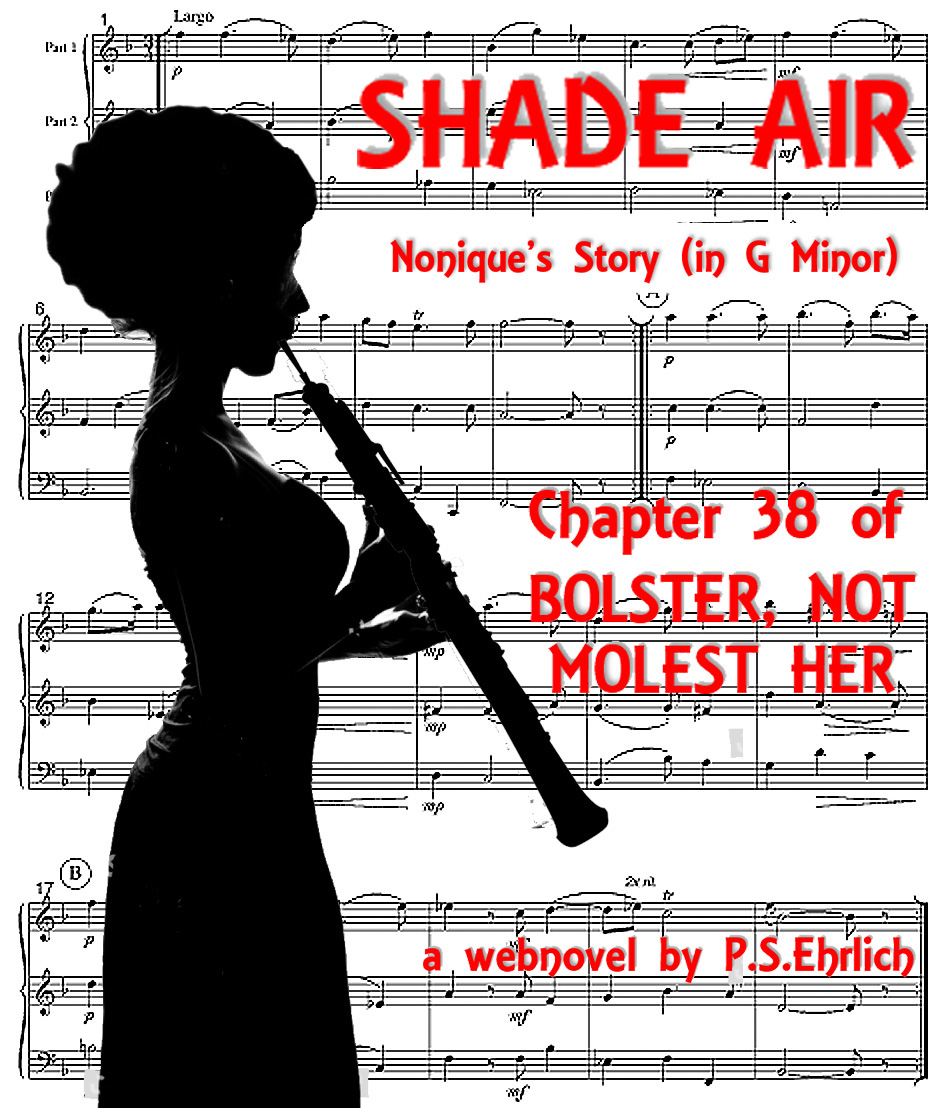

Chapter 38

Shade Air

|

Airs and graces: hymns and prayers. Shades and curtains: ghosts and graves. |

*

South Holloway Street is the buckle on The City’s Black Belt. It borders one side of a namesake park where the Curry family reunites every 4th of July to celebrate the birthday of their patriarch Ezekiel, who claims every year that all the fireworks in town are being set off in his honor.

Big Zeke came from sharecropping stock in Choctaw County, Alabama, where he lost his first wife to tuberculosis and his livelihood to boll weevils. With four young sons and a freshly-wedded second wife in tow, Zeke took part in the Great Migration northward to The City. Midway there the Currys were joined by newborn Catherine, who from an extraordinarily tender age took charge of kith and kin and never relaxed her grip during the next sixty years.

(“That doggone Cat got claws in her paws!” Big Zeke would often say.)

The Currys settled on South Holloway and Zeke went to work at a meatpacking plant, which “sure beat pickin’ cotton—cain’t eat that, no matter how deep you fry it!” Over time he sired seven more children (the youngest, Delores or “Duz” as the dozenth, would be only a decade older than Nonique and more of a big sister than a great-aunt) in between burying Cat’s mother, marrying her best friend, and burying her too after Duz was born:

“I done my share o’ bein’ fruitful ‘n’ multiplyin’—‘n’ payin’ off undertakers too!”

Cat Curry, having witnessed this marital mortality, took vows of spinsterhood but got talked out of them by amiable Abram Randle, who was part of the CIO’s effort to organize packinghouse labor. This crusade, remarkable for its integration across racial and ethnic lines, helped Big Zeke keep putting meat in his offspring’s many mouths:

“Bad enough bein’ saddled with all these chillun, ‘thout ‘em wantin’ to be fed three times a day!”

Cat never quite forgave Bram for winning her heart while still in her teens. To compensate, he was frequently urged to make a better life away from the Stockyards for Cat and their firstborn Alfreda, who from infancy was told in no uncertain terms that she was going to graduate from high school and go on to college before she’d be permitted to so much as think about wife-and-motherhood.

Cat’s spouse and child knew better than to disobey. Bram learned the electrical trade while in the army and got into the refrigeration business after WWII. Freda studied hard, received straight A’s, and made plans to become a teacher. The Randles were augmented by postwar son Curry, called “Babe” by everyone except his mother, who said after all the grief he’d put her through—twelve pounds at birth!—he must be intended for either the church or the penitentiary; so she’d see him standing in a pulpit or lying in a casket—his choice. (Babe pursued his love for music into a career as an African Methodist Episcopal choirmaster.)

Alfreda attended the State University, pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha, and roomed with Leatrice Higden who adored babies and couldn’t wait to become a delivery room nurse so she could help bring more into the world—even after she met Mama Cat and heard, at length, about the miseries of unloading Babe. Freda the future teacher preferred children who were old enough to be disciplined without causing tear-floods, yet not so old as to require what Big Zeke defined as “serious ass-whuppin’.” For the foreseeable future she didn’t anticipate kids would be calling her anything but Miss Randle or Cousin Freda. (Zeke’s progeny now included forty other grandchildren.)

Then she met Vernon Smith. He was six-foot-eight, with proportionate fingers that could work wonders with a basketball, and an innate ability to juke his way out of any predicament. These had served him well growing up (and up, and up) downstate in Little Egypt, where racial attitudes were much the same as in deepest Dixie; they also won him a full scholarship to the U., a position in its starting varsity lineup, and letterman’s status at a time when that still meant being a Credit To His Race.

“Shucks! T’warn’t nothin’ more’n chile’s play!” he would smirk, particularly when talking to a pretty girl.

Most of the Alpha Kappa Alpha ladies were pleasantly aware of Shucks Smith, and he worked his systematic way through their affections. Leatrice Higden remained immune, having fallen for Airman Second Class Marvin Wilmore of Chanute Air Force Base; but Alfreda Randle, to her amazement, found herself most heavily smitten.

(Not for nothing had Shucks lettered as a power forward.)

She was the last in her sorority to succumb—“I always save the sweetest fo’ dessert,” he told her in his best Sam Cooke voice—and she was the one who consoled Shucks when The State dropped out of contention his senior year after ranking in the top ten nationwide. Freda introduced Shucks to her folks: Bram was laudatory, Babe a hero-worshiper, and even Cat gave conditional approval of Vernon Smith’s being a college man—albeit one who had to ride his own athletic coattails to earn a degree.

Which he then did nothing better with than play professional basketball. In those days the NBA had only eight franchises, none of which drafted Shucks; he landed a tryout with Cincinnati, but got lost in Bob Boozer’s gold-medal shadow. Bram Randle offered assistance in finding him a good steady job in refrigeration, but Shucks went and signed with the Harlem Globetrotters, thereby donning a permanent duncecap in Mama Cat’s remorseless eyes. Freda too was disillusioned: her heart beat high for daring young men on flying trapezes, but she had only scorn for circus clowns.

So they parted. Freda, after serving as Leatrice’s maid of honor, returned to The City and began her sadder-but-wiser teaching career. Then the Globetrotters came to town, competing with a squad of college all-stars in what was billed as “the World Series of Basketball.” Bram took Babe to see this; Babe teased Freda into accompanying them; the Trotters minimized their trademark antics to prove the legitimacy of their chops; and Freda got smitten all over again with Vernon Smith—this time for keeps.

Abe Saperstein was forming a new league to rival the NBA, and handpicked Shucks to play on The City’s team. Shucks took Freda out to celebrate at the Regal, where he amazed her once more by proposing marriage. This resulted in an honest-to-God elopement: the happy couple drove down to Chanute so Mrs. A2C Wilmore could be matron of honor, and tied the knot while the entire base was distracted by Gus Grissom’s near-drowning after his Mercury spaceflight.

Freda would feel almost as sunk as Liberty Bell 7 when her blissful telegram home triggered this reply from Mama Cat:

we did not put you through college just to marry a dribbling fool

And that was the final word (for awhile) from South Holloway Street.

The newlyweds took an apartment in Bronzeville; Shucks played a season with the ABL Majors; and Freda barely completed a second year of schoolteaching before Vernonique Curry Smith made her Juneteenth debut. Leatrice Wilmore wired congrats and regrets at not being on hand for the L&D, while Grandma Cat resurfaced—"like ol’ Moby Dick,” muttered Shucks—to take charge of mother and newborn, and behave as though eleven months hadn’t elapsed since last she’d spouted.

“Not the slightest doubt but this child is purely a Curry,” declared Cat, cradling baby Nonique in her unshakable arms.

“Ain’t nothin’ like a birthin’ fo’ gettin’ a free see-gar!” added Big Zeke outside the nursery window, puffing on one of Shucks’s robusto grandes. His own seventy-second birthday would be celebrated two weeks later at South Holloway Park, with Nonique paying carefully-hydrated respects for a few pre-pyrotechnic minutes.

And life went on swimmingly till year’s end, when the American Basketball League abruptly folded and left the Smiths high and dry.

Shucks hooked up with some barnstorming hoopsters to try making ends meet; his wife and child left their Bronzeville apartment to move in with the Randles; and Grandma Cat broadcast the three little words TOLD YOU SO in every way expressible.

Nonique would later guess this was when her parents first assumed Dickensian traits: Freda vowing I will never desert Mr. Micawber and Shucks affirming that Something will turn up. And something actually did: himself on the roster of the St. Louis Hawks, thanks to a lucky break (of another power forward’s leg) that enabled Shucks to juke his opportune way out of another predicament.

The Smiths had three good years in St. Louis, and Shucks had three good seasons with the Hawks—twice making it to the NBA conference finals—before being summoned back to The City in the expansion draft for the brand-new Bull-onies. At the same time his household expanded to make room for Vernon Randle Smith, whose lusty howls (“like Mowgli trying to act like a wolf cub”) darkened Nonique’s earliest memories.

Randle would be taught to call Shucks “Dada,” but to Nonique her father had always been “Taw”—her infant pronunciation of tall. A favorite family portrait showed her clinging to Taw’s shin, gazing upward for miles and miles to see his beaming face. By the age of four she was able to take conscious pride in Taw’s accomplishments, bragging on them to fellow preschoolers—till karma came home to roost at the International Amphitheatre, where Taw broke his leg and was out for the rest of the season.

He worked long and hard to recuperate, regain his form, recoup his jukes. Then he jumped to the new American Basketball Association and had the best year of his career, playing for Pittsburgh with Connie Hawkins and the champion Pipers. Nonique made a new set of kindergarten friends and anticipated a long stay in Steeltown; but after only one season the team upped stakes and moved to Minnesota, where Nonique had to start over from scratch with a different bunch of first-graders.

Which was nothing compared to the scratch Taw had to start over from when he got sideswiped by an Oakland Oak, reinjuring his leg worse than before. This, it seemed, might be The End: Vernon Smith was over thirty now, convalescence took longer, and he had a wife and two growing children to support. Freda nudged him gently toward a new vocation, say in physical education; but Shucks couldn’t bear to bow out as a player just yet.

He made the rounds of training camps, and his knack for opportune juking pulled him through once more: this time as a veteran reserve with the Kentucky Colonels. Freda, however, had been hauled out of four different homes in four different cities in as many years, and drew the line at moving to Louisville.

Her parents had left Holloway Street for a townhouse in Ferndean Gardens, a new cooperative development (“not the projects!”) in Riversgate, which was as far south as you could go without stepping across The City limits. Here Freda was determined to settle down, give Nonique and Randle a stable upbringing, secure an anchored base for them and herself—and Shucks too, wherever else the bouncing ball might take him.

(I will never desert Mr. Micawber!)

Nonique was used to Taw being away on the road for weeks at a stretch, and didn’t miss him more than usual. She knew girls and boys whose daddies never came home at all, their whereabouts unknown. One such was LaVinia Wilmore, daughter of Leatrice (“Aunt LeeLee”) and Sergeant Marvin (MIA in Vietnam). The non-missing Wilmores also relocated to Ferndean Gardens, giving Nonique and Randle automatic best friends in LaVee and her little brother Reggie.

Nonique and LaVee were the same age, same race, same gender, and had both come from gypsylike backgrounds (pro ball vs. military) but otherwise they were complementary opposites. Nonique was the pretty one, the quiet one, the nice girl, the obedient girl. LaVee was the cute one, the noisy one, the wild child, the “sassyfrass.” She took the lead in double-daring-do, able to turn any dull chore into adventurous fun; Nonique yanked them back from toppling into truhhhhble, and saved LaVee’s sassyfrass from getting smacked—some of the time.

Ferndean Gardens was a wonderful place to grow up in. It was run by a tight-knit community; the adults looked out for each other’s kids, and not simply for self-protection; gangs and drugs were kept at bay. No one who lived there was rich but most were fairly comfortable, holding down jobs at factories and industrial plants, with the occasional teacher like Freda or nurse like LeeLee. There might be truhhhhbles to contend with, yet they were outnumbered by joys.

For Vernonique Smith, the foremost joy was instrumental music. What her father’s fingers could do with a ball, or her mother’s intellect with self-discipline, or her Uncle Babe’s lungs with breath control—all these Nonique could do with woodwinds, beginning on a plastic recorder in second grade.

“That child is blessed with Talent, and you know I don’t use that word lightly!” said Miss Fanny Hooker, an old friend of Grandma Cat’s who was constructed from much the same armor plate. (No kid ever laughed at her name more than once.) Miss Fanny’s music lessons were neither cheap nor easy, but Nonique excelled and was soon starring in recitals on the flute. Uncle Babe encouraged her interest, buying her record albums, taking her to the Summer Festival and Orchestra Hall. There she first heard Ray Still play Bach and Mozart live, her eyes filling with tears at his oboe’s ringing singing tone, till she’d have to close them and sit weepily enraptured.

“Why you wanna go all the way up there just to take a sad nap?” LaVee would ask.

There were no words to explain.

Not many of Nonique’s peers shared her partiality to the classics. LaVee could enjoy any musical genre so long as it was loud and rhythmic and danceable-to, preferably as part of a crowd. (From the age of nine her ambition in life was to appear on Soul Train.) When Mrs. Mosely the docent took their fourth-grade class to a Symphony Youth Concert, LaVee almost had to be tied down to prevent her boogeying in the aisle to the Radetzky March.

“(Just sit and clap along!)” hissed Mrs. Mosely.

“Aw, let’s put our HANDS together!!” shouted LaVee, and the entire Hall suited deed to word. Conductor Henry Mazer thanked them for their enthusiastic response, but Mrs. Mosely gave LaVee the stink-eye all the way back to Riversgate.

Miss Fanny Hooker, strict as she was, would never do that; yet she wasn’t wreathed in smiles when Nonique asked about taking up the oboe. “That is a challenging instrument, a difficult instrument. The double reeds, the embouchure, the articulation—they need a world of practice and an eternity of patience, child! Are you willing to bear with that?”

“I can try,” said Nonique. And the first time she laid hands and lips on an oboe, it felt like it was part of her—as though she’d sprouted wings that might someday allow her to fly and swoop and soar, if she could learn how to use them.

“Why you gotta be blowing on that thing alla time, just to make it honk like a goose?” LaVee would sniff. “You better hope you grow boobs before you sprout any wings, sistah!”

Nonique progressed beyond duckcalls to vibrato to the chromatic scale to alternate fingerings and, in due course, to the limits of elementary oboe education. Miss Fanny and Uncle Babe found an affordable intermediate instructor near Greektown (“of all the places on the Lord’s good earth!”) in old Mr. Nikodemos, who as a youthful junk dealer had bought a broken oboe, mended it, mastered it, and gone on to play it in taverna ensembles.

“Hoo-wee!” went LaVee. “If you gonna start hanging round with an old white man, why not one who looks like Burt Reynolds?”

Nonique had a few forebodings, but soon warmed up to Mr. Nik who was exacting yet praiseful when merited; and also to Mrs. Nik who gave her Greek treats that she at first only nibbled at so as not to hurt any feelings, before developing a taste for them which made her feel very cosmopolitan.

Mr. Nik taught Nonique how to play the full range of the oboe and do it expressively, with phrasing and dynamics, building up her strength to tackle longer pieces without fatigue. He spoke to her about the future—making her own reeds, entering competitions, applying for scholarships that might pay for most or even all expenses at a fine conservatory.

The Lord knew Nonique could use such funding; she was hardly likely to be a grand heiress. Taw didn’t rake in big bucks as an aging ABA reserve, and while he never failed to fork over his share of what might as well be called child support, there were whispers that he spent the bulk of his balance at the track, in gambling houses, and on “image.”

Louisville sports reporters dubbed him “the Ol’ Colonel” and Taw gloried in that role, growing a moustache and goatee, wearing tailor-made white suits offcourt and twirling a gold-topped cane. He could always be relied on for a colorful quote, and the clippings he sent home for Nonique’s scrapbook contained more of his chatter about games than how often or how well he played in them.

Kentucky was a prime contender all three of Taw’s seasons there, going to the ABA championship series his second year. He promised Freda he’d retire if the Colonels won it, but they lost game seven in a heartbreaker. The next season they compiled the best record in league history; but Taw tore ligaments in his knee just as the playoffs started, Kentucky bowed out during the first round, and Vernon Smith announced his retirement a day later.

(“Now he got a use for that fool cane,” said Grandma Cat.)

He seemed a shoe-in for a job as color commentator at one of the Louisville TV or radio stations, but no shoe fit and apart from rehab, Taw was left at very loose ends. Then Charles O. Finley came to his rescue —if that was the right word—by hiring Taw for the last-place Memphis Tams, whose paychecks bounced higher than their basketballs.

Had something turned up? Nothing but turnips for two grotesque years of repeatedly getting fired and rehired, Charlie-O-style. Nonique put away her scrapbook and struggled not to feel shame, nor to resent her father’s dwindling to a shadowy figure on the fringe of her life.

It was around this time that she began to dream of the Shady Man.

Who had no connection to Taw (she was sure) but probably stemmed from what Freda euphemized as “becoming a woman”—though Grandma Cat said that wouldn’t occur till Vernonique’s wedding night, so long as Cat had any breath left in her body. Whichever woman-tense might be accurate for a sixth-grader (became? becoming? will become?) Nonique was shy around boys; especially compared to LaVinia Wilmore who could juggle a dozen crushes at once, including whichever one of the Chi-Lites she favored most at the moment. Sixth-grade boys took increased notice of them both; LaVee reeled them in as if fishing off a pier, but Nonique (no longer able to brag on her dad) stood by tongue-tied, shifting from one shapelifying leg to the other. Shyness wasn’t the only reason: most of these boys were as brattily immature as Randle or Reggie Wilmore, and (as Miss Fanny would say) it was “challenging and difficult” to picture any of them ever having the stuff dreams could be made of.

Unlike the Shady Man.

Arriving in Slumberland, Nonique would meet the Shady Man in some tranquil poetic setting lit by candlelight—a Paris bistro, maybe, or a loge in an old-timey theater. She wouldn’t be able to make out his features in the flickering dusk, but didn’t need to since she knew they were of one mind, one heart—as simply intimate as Schumann’s Second Romance for Oboe and Piano. The Shady Man would pour effervescence from an uncorked bottle of champagne; they would clink costly goblets, entwine their arms and drink till the bubbles ran up their noses...

Night after night after night.

Did her mother still dream of Taw that way? Did she relive his proposal at the Regal, their elopement to Chanute? Better that than be reminded of his riding the has-been bench for the moribund Virginia Squires, till the inevitable day he messed up his knee again. And even then he refused to throw in the towel, turning up like a washed-up turnip at next year’s round of training camps for one last try.

He was out in San Diego when Frank Deford recognized him—Didn’t you used to be Shucks Smith?—which led to that “On the Rebound” profile in Sports Illustrated. Only a page and a half, but it lent the Ol’ Colonel’s muleheaded tenacity a quixotic valor sprinkled with winks and shrugs and jukes. No one signed him to play ball that season (the ABA’s finale), yet his mention of all the vitamins he’d consumed during his comebacks inspired Universal Nutrition to have Taw make a commercial for their health-food markets.

“Listen up, folks! This here’s the Rebounder!”

And just like that, he was launched into semicelebrity.

(“First a hoopster, now a huckster,” grumped Grandma Cat.)

Vernonique could’ve done without seeing the “gentleman of leisure” suits he chose to Rebound in—on TV, on billboards, in newspaper and magazine ads, at every Universal Nutrition Market in The City. That said, she voiced no complaint at Christmastime when Uni-Nute money bought her a splendid new Yamaha oboe; though all the menfolk from Big Zeke down to Randle cracked jokes about her popping wheelies on it.

Taw at least applauded her medley of holiday carols. “That’s cold—that is cold, baby girl! Someday you gonna be playin’ that thing for the Queen o’ England!”

And she’d want him there to hear her do it—if he’d lose those pimpish outfits first. Too many of her fellow eighth-graders subscribed to that sartorial regimen, in Nonique’s opinion; part of the interminable debate about straightened hair vs. natural Afros, dressing/talking/acting “street” vs. dressing/talking/acting “white,” etc. etc. and so forth.

“I don’t see what all the fuss is about,” ironic Reuben Burns would say.

“Hey, man! Where yo dog at?” insensitive passers-by would ask.

Reuben, cupping a hand behind his ear: “Sounds like some mutt’s barking at me.”

Nonique would cup a righteously defensive hand inside his elbow, and the mutts would change their tune to “Hey, man! That yo seein’-eye fox?”

No denial by Reuben, tapping his cane on the junior high school linoleum.

He and his mother (the extensively-traveled AME missionary Jarena Otway Burns) had recently come to Riversgate after a prolonged tour of Bangladesh. Grandma Cat could not comprehend how Widow Burns could drag a boy that young and blind through a foreign country so afflicted by war, flood, and famine, no matter how many good-work points the Lord might award them. But Reuben was capable of looking out for himself, with a little help from his friends—a chocolate labrador named Kukura, that Reuben wasn’t allowed to bring to school; and a classmate named Bruiser Poole, whose presence restrained raillery to Reuben’s being called “Ray Charles,” “Stevie Wonder,” etc. etc. and so forth.

Girls giggled interestedly around Reuben, at least when his misshapen eyes were shielded by dark glasses. He seemed a bit older and worldlier than most students at Riversgate Junior High, with an air of detached remoteness that many girls took as a personal challenge to penetrate—none more so than madcap LaVee, who claimed Reuben was faking blindness to trick women into shedding their inhibitions in his presence. To prove this, she’d flash her bra and drawers at him while watching for a giveaway reaction.

“See? See that? He got sweat on his brow!”

“Probably ‘cause he can guess how crazy you’re acting!” said the scandalized Nonique, tugging LaVee’s skirt back down.

Reuben ran unruffled fingers over a keyboard in the Riversgate band room: “It was an itsy-bitsy teenie-weenie yellow-polka-dot bikini...”

“You SEE? He SAW!”

“You’re wearing pink,” Nonique reminded her.

Ironic arpeggio by Reuben.

He was a budding virtuoso on a wide range of instruments, from mandolin to sitar, but especially adept at ivory-tickling. At school and church he and Nonique made beautiful music together: Schumann’s Three Romances, Carl Nielsen’s Fantasy Pieces, Saint-Saëns’s Sonata for Oboe and Piano. Their spending a lot of time off by themselves, rehearsing and “jamming” and listening to LPs, had predictable side effects—from LaVee’s “So is he alla time trying to ‘feel yo face?’” to Uncle Babe’s “How soon should we reserve the wedding chapel for you two?”

Nonique’s lips were primly sealed; but Reuben had concluded one of their classical jam sessions by asking if he could kiss her.

“Um, sure,” she replied. (Would this count as her First Kiss? Given how she hoped she wouldn’t glimpse his blemished eyeballs through his Ray-Bans?)

It went okay: he felt good, smelled good, tasted good, and she kept her own eyes shut. But as an audition for a live-action Shady Man, it was a bust—no pop of champagne cork, no passionate fizz of intoxicating bubbles. They were compatible in every other way, like-minded, well-matched; it would’ve been so convenient for Reuben to be her Shady Man Made Flesh, even without perfect sightliness. Yet as Grandpa Bram always said: you can’t hope to make a sundae if your ice cream’s in an unplugged fridge.

So dream on, Vernonique—night after night after night...

Then came Thornford. Riversgate’s senior high school was named for Rowland Thornford, “the black Ambrose Bierce,” whose grimly sardonic stories were now staple texts in Language Arts classes. You’d expect a school of that name to look like a Gothic citadel or crumbling tenement; but Thornford High, Home of the Ravens, was built along Bauhaus glass-box lines and regarded (not always approvingly) as “modern” in outlook. Though not overprovisioned with resources, its graduation rates were high; many students went on to earn college degrees; a significant percentage of The City’s younger black doctors, lawyers, and other professionals were Thornford alumni. There was also a boastworthy music department under the direction of Mr. W.C. “Handy” Lynn, who’d been following Nonique’s progress as avidly as an NCAA coach would monitor an outstanding sports prospect.

“Good oboists are worth their weight in gold—no, platinum,” said Mr. Lynn, preadmitting Nonique to the Thornford Concert Band before her first day as a freshman. He had fifteen clarinets, most of them upperclassmen selected after rigorous evaluation; but Nonique was the lone oboe.

Band work was a sorely needed diversion for Nonique after her bittersweet parting from Reuben Burns, whose mother’d decided their missionary efforts were needed in China where an earthquake had just killed a quarter-million people.

“But what about Kukura?” worried Nonique, scratching behind the lab’s chocolate ears. “Aren’t there like quarantines ‘n’ stuff? And don’t those Chinese Communists hate running dogs? Not that you let Kook run around that much...”

“Well,” said Reuben, “I don’t think they’ll eat her, though I do hear that she looks delicious. And maybe they’ll quarantine us both; then I’ll have time to finish my Requiem.”

Not the Requiem again. Nonique hated when he talked about that weird blend of Bartók and Jacques Brel, sounding as though he were composing it for himself. “Reuben? We ever gonna see each other again?—oh, y’know what I mean...”

“Not like I’d like to. But we’ll always have Schumann. Here’s looking in your direction, kid.”

Nonique wept a little as she kissed him goodbye, partly because (again) there was no spark when their lips touched. Then too, she was left without even a facsimile of a boyfriend at the very start of senior high; leaving her prey to full-grown men who shaved and smoked and had driver’s licenses, not to mention wolfish intentions toward freshgirl lambs. What she needed wasn’t a boyfriend but a bodyguard—someone like Bruiser Poole.

“Forget him,” sniffed LaVinia as she braided Nonique’s hair. “Him ‘n’ ‘Love Bite’ think they’s made fo’ each other.” (Louder sniff, resentful of snooty Elouise Briggs for pre‑empting a nickname ideal for LaVee.) “How ‘bout you give ol’ Winth-ROP a whirl?”

“Oh please!” went Nonique. She’d known Winthrop Eshton since Miss Fanny Hooker’s recitals; he could play a mean trombone but had a meaner mouth off the instrument, going so far as to argue with Miss Fanny about arrangements and getting away with it. Now he lived and breathed for participation in the Thornford Marching Band, reportedly wearing his uniform and plumed shako even in bed—“Eww!” went the girls at that grisly image—and deriding Nonique for her exemption from marching duties.

“It’s not band music if you aren’t up on your feet, out on the street, in a parade! Sitting all day on a chair in an auditorium’s nothing more than fooling around!”

“Better’n fooling around with ol’ Winth-ROP,” said LaVee, handing Nonique a mirror for braid inspection. “How ‘bout Stumpy, then? He’s always checking you out, be more’n glad to guard yo body—”

“Hush now!” went Nonique. George Sumpter was built like a rain barrel and used that as an eye-level excuse to ogle bosoms. “Which he wouldn’t do so much if you’d let me wear what I wanna wear to school.”

“Girl! Am I not yo very best friend?”

(Sigh.) “Yes, you’re my very best fr—”

“Are we not practically cousins, practically sistahs?”

“Yes, we’re practically cou—”

“Do I not owe it to you to help you look yo best? Anybody object to that fine outfit I picked out fo’ you to wear tomorrow? No ma’am, not even Miz Cat! And if y’own grandmom don’t object, why on earth should you?”

At least the close-fitting dress hanging on the closet doorknob would keep Nonique’s curves decently covered, and by her favorite shade of blue; whereas LaVee’s blouse was half-unbuttoned (as usual) so the world could enjoy her native shade of brown.

Nonique scowled at LaVee’s cleavage. “If you don’t button that up, Stumpy’s gonna dive in ‘n’ go deaf. You’ll have to yank him out by the ears so he can come up for breath!”

“Ooooh girl, what you saaaaaaaid...”

There wasn’t much they didn’t saaaaaaay to each other. But not long into their first semester at Thornford, Nonique was asked to do something that had to be kept clandestine especially from LaVee.

Possibly due to her musical mentality, Nonique was very sharp at math and aced all the quizzes in Mrs. Dent’s Algebra class. Alas, the same could not be said for Addie Mae Anderson. If a Frolicsome Frivolette pageant were ever staged, she would qualify as an instant finalist; and if a short attention span could be considered a talent, the tiara would go to Addie Mae without question. But she’d only been admitted to the eleventh grade after scrambling to stay off academic probation at school—and keep out of solitary confinement “till you get them grades up!” at home.

For a supergregarious girl like Addie Mae, isolation was unendurable. Even in the womb she’d demanded a second egg cell be fertilized so she could have a twin companion—who, as it turned out, was the only person unmoved by A.M.’s crying alone in her room after flunking yet another subject.

“That’s what you get fo’ bein’ a dizzy-dimpled simp!” her twin would shout through the closed door.

“You the bigger dummy!” she would sob-respond, hoping to kick off a conversation. “Hey, you still out there? C’monnnn, talk to meeee...”

Addie Mae was neither stupid nor lazy; she always tried extra hard to concentrate on her studies, memorize enough of them to answer enough questions correctly so she could continue to circulate and jubilate. Everyone at Thornford (except her twin) loved A.M. and wanted to help; but she could reduce the most seasoned tutor to a state of exhaustion. One such exhaustee said coaching her was like trying to herd a sugar-high kindergartener through a field trip to a puppy farm.

Vernonique had helped LaVee, Reuben, and other friends cram for math tests; she’d even pounded some arithmetic through Randle and Reggie’s stubborn little skulls. So after consulting her mother on instructive strategy, she accepted Mrs. Dent’s challenge and agreed to try tutoring Addie Mae Anderson. Five minutes into her first attempt, she fully grasped the sugar-high puppy-farm analogy:

“—you SO purty not like that last sourgrapes couldn’t teach a toad how to hop hey ain’t yo daddy that Rebounder man on the TV? he SO handsome I do loves me tall dark ‘n’ handsome men ‘ceptin’ this one beanpole Dwayne? he gone now but we dated some and tall? I tell you he was taller’n a traffic light but nowhere near as bright ‘n’ you cain’t date a man that dumb fo’ long you just cain’t his dumbness’ll rub off on you so who YOU datin’ girl? I know you just a freshie but SO purty why when I was yo age the boys filled up the whole front yard ‘n’ my daddy’d say ‘Addie Mae!’ he’d say ‘Count o’ five I’mma turn the hose on that pack o’ hyEEnas!’ but ‘Daddy!’ I’d say ‘What can I do?’ I’d say wasn’t like I ax’d ‘em to fill up the whole front yard oh listen to me gibbetin’ on while you wait so patient I sure don’t wanna dispoint Miz Dent again she such a nice lady not like that sourgrapes I had for Basic Math? first time I took it hadda take it twice Miz Dent she say to me ‘Addie Mae!’ she say ‘You gotta pay closer ‘tention!’ but ‘I TRY!’ I tell her ‘I TRY Miz Dent!’ but doin’ that homework? takin’ them quizzes? why it feel like when yo popsicle slurps off’n its stick ‘n’ lands onna hot sidewalk ‘n’ what can you do when it all melts off’n yo MIND?—”

(This Bicentennial Minute was brought to you by Miss Frolicsome Frivolette.)

Nonique did her best to translate the x’s and y’s of abstract formulae into graspable scenarios, such as how much it would cost to design, prepare, and market different ensembles of clothing. This Addie Mae could readily understand: she was a habitué of thrift shops and church bazaars, mixing and matching ingenious new wardrobes. Her twin dismissed this knack as “bag-lady boogie,” but A.M. set fashion trends for much of teen-female Thornford and definitely LaVinia Wilmore, who closely tracked how she dressed and did her ‘do and painted her face and polished her nails and carried on as a partygirl paragon.

“Ever’body needs a role model,” LaVee would say. “Her role is bein’ my model.”

Nonique knew LaVee would never-forgive-her-as-long-as-either-of-them-lived for not being asked to sit in on the Addie Mae tutorials, or even to know they were underway. But that would double the puppy-farm and treble the sugar-high, and could not happen till Nonique’s illustrative examples strung a rope ladder from A.M.’s cascading stream of consciousness to potential passage of Algebra.

Exam time came. The rope ladder, though flimsy, did not snap; Addie Mae Anderson received a tolerably adequate C-, and so adopted Nonique as her personal good-luck charm. Invited to sit with A.M.’s clique at a crucial football game against archrival Millcote, Nonique asked “Can my best friend LaVee come too, she’s like your biggest fan?”; and so avoided excommunication when the whole tutorial business was at last made public.

|

SAY IT NOW ‘N’ SAY IT PROUD!! HERE WE BE—THE LOUDER CROWD!! |

Steered by senior Marquita McLeod, this was not the snobbish coterie dominated by Elouise Briggs’s big sister Rochelle, nor the earnest overachievers led by Winthrop Eshton’s big sister Aimee. The Louder Crowd simply sought to have the best possible time at the highest possible volume, and no social get-together could be considered a Party without the Crowd’s involvement.

LaVee, wearing a double-breasted storm coat just like Addie Mae’s, was torn between delirium and smugness at being among the Crème de la Crowds at the Game of the Year. Nonique, huddled by her side in a hooded polyester parka, wished they weren’t outdoors on such a windswept November evening. LaVee had palpitations for five different varsity Ravens, elevating each in sequence to soulmate-status as he ran or passed or caught or blocked; Nonique couldn’t tell any of them apart in their black jerseys in the chilly darkness, and wished she’d gone to see Bugsy Malone instead. At least she and her oboe didn’t have to march with Winth-ROP’s trombone over that frigid-looking unacoustic field.

“Lookit lookit there’s Fair Catch!” went LaVee as the Ravens lined up for a kickoff return. Nonique knew that “Fair Catch” was Addie Mae’s twin brother Eddie Ray Anderson, who habitually signaled for fair-catch receptions of kick or punt. Moreover, he was deemed to be a fair catch by girls like LaVee, despite Eddie Ray’s longtime liaison with a haughty majorette named Rumah Myers, who reputedly had Creole blood and could cast voodoo hexes: “bad mojo with a spinning baton.”

LaVee risked Rumah’s wrath by openly sighing and moaning and squealing for Eddie Ray, even outshouting the rest of the Louder Crowd in a concerted

|

Two bits! Four bits! ‘Fro needs a pick! Ever’body stand up ‘N’ do the Funky Chick! |

late in the fourth quarter when the Millcote Broncos kicked off after taking the lead 21-20. As the football descended and Eddie Ray began to raise his arm for the usual fair catch, LaVee shrieked his name at the top of her lusty lungs, piercing the tumult and diverting E.R. from the task at hand; his facemask turned her way as the ball caromed off his chest and into the crook of his unraised?/upraised? arm. A second later three Millcote Broncos threw him to the turf, where five others piled on top.

Burst of referee whistles, amid which LaVinia turned to Vernonique and said “He was looking at you when it happened!”

After they exhumed Eddie’s body, his arm was ruled to be more up- than un-; so Millcote got socked with interference and personal foul penalties, Thornford scored a last-minute field goal, and the Ravens won the Game of the Year. Eddie Ray received a chanting stamping tribute as he was loaded on a stretcher and carried off the field; but Addie Mae was fit-to-be-tied at being told she had to go with E.R. to the E.R., thus missing the Louder Crowd’s postgame bash-o-rama.

“Why I gotta go?? Wasn’t me got knocked down ‘n’ stomped on like a big ol’ clumsy dummy!!”

LaVee felt even more indignant, since she and Nonique lost their Golden Ticket to the bash-o-rama when A.M. left. Nonique doubted their folks would’ve sanctioned their being present at a probable saturnalia, but LaVee sniffled all the way home and there got confined by Aunt LeeLee on Monday after incubating a fullblown case of the flu.

That’s what you get for not wearing a hooded parka, thought Nonique; though not too snidely since she knew LaVee feared being sick all week including Thanksgiving, when she’d normally eat her weight in turkey ‘n’ trimmings. “And not gain an ounce, ‘cept where it counts!” (Shake-shake-shake of sassyfrass.)

That same Monday Addie Mae had an anxiety attack about Mrs. Dent’s new unit on inequalities, which A.M. thought had been eliminated by the civil rights movement. Nonique was implored to come to the Andersons’s house for that afternoon’s tutorial:

“I gotta go straight home ‘n’ babysit that Big Clumsy Dummy ‘n’ his big busted armbone fo’ free after he gone ‘n’ ditched a whole day o’ school my momma’s waitin’ fo’ me t’get there so she can go t’work she say ‘Addie Mae!’ she say ‘He yo twin brother!’ like any o’ that’s my fault him ‘spectin’ me to wait on his hand ‘n’ foot—”

The Andersons lived in Douser Dell (“the Dow-Dee” to street-linguists), a bleaker, more projectlike part of Riversgate. Daddy worked at the paint factory and Momma cleaned offices, both with frequent overtime obligations. The twins were assigned to keep the house tidy; but since neither spent much time there, Momma had to pick up the slack. (“Z’if I didn’t spend twenty-four hours a day on my feet cleanin’ the rest o’ the world already!”)

In the Anderson front room was a davenport sofa, and lolling upon it was Eddie Ray in a red plush bathrobe and red plush slippers, with his right arm in a cast and sling. Wedged between his left ear and shoulder was a telephone receiver, and from it came a stream of almost-decipherable vitriol.

“Hold on, baby,” E.R. told the phone. “Gimme ‘nother pop!” he told A.M.

“I am not yo waitress!” snapped Addie Mae. “F’that’s Rumah, tell her t’bite yo head off ‘n’ be done with it!... C’mon,” to Nonique.

”Hold on,” Eddie interposed. “Who this you brung home fo’ me to see?—naw, baby!” (into the phone, hastily) “Just sayin’ hey to my stupid sis! ‘Hey, Stupid Sis—’”

“Shut yo mouth, Eee-Yore!”

Nonique could detect no trace of twinness in the Anderson siblings. Not only were they different sexes, but Eddie Ray had none of Addie Mae’s cinnamon-skinned/eyed/haired beauty. His face was dark and comical, rubbery-featured with roguish eyes and elastic lips, like photos Nonique had seen of Louis Armstrong. His voice added to this impression: rich, slow, deep, gravelly, the polar opposite of Addie Mae’s “gibbeting.”

“...but baby, I still got one strong arm can hold you tight... heh heh heh heh... ain’t nothin’ wrong with my legs neither, dance all night till the ol’ rooster crow... heh heh heh heh... ‘cock-a-doodle-doooo’... hey Addie! I ax’d you fo’ ‘nother pop!”

“Ignore that clumsy dummy,” A.M. told Nonique in the cluttersome dining room, clearing a space for their Algebra texts and notebooks, then giving her guest a sudden apprehensive glance. “Unh-UNH! Don’t do it, girl! Don’t even think ‘bout fallin’ fo’ him! You too good, too smart fo’ that—we find you a really fisticated type f’you t’date—”

But, of course, it was too late.

Vernonique Smith had found her Shady Man.

Pop went the cork; pffffohhh went the effervescence.

She tried to pay this no-never-mind, burying her brain and Addie Mae’s in the intricacies of unequal equations; and for awhile she almost succeeded. Then from the front room rose a rich, slow, deep, gravelly sound of heavy breathing that edged toward all-out snores. Over which crackled a fiery new stream of audible vitriol:

“Eddie Ray Anderson?? You better HOPE you didn’t fall asleep on me!!”

“‘Scuse me a sec,” Nonique told A.M. Up she stood; over she marched; out from under E.R.’s sagging jaw she plucked the phone; up she hung it with a decisive click.

Eddie’s eyes popped open, assimilating what had just happened; then his elastic lips extended from ear to ear. “Sweet thing, you saved my life!” His free hand reached out; in it was a Sharpie marker. “Sign my cast... ‘n’ put yo phone number after yo name... heh heh heh heh...”

And there they were: bubbles running up Nonique’s intoxicated nose.

By Thanksgiving Day she was ready to confess all to LaVee, beg her pardon for claimjumping one of her crushes, and beseech her aid in winning Fair Catch’s heart. Also in eluding any reprisals by Rumah Myers, who’d publicly dumped E.R. for hanging up on her (also for inconsiderately breaking his arm right before the holiday season) but was not the sort to tolerate her love-dumpster being sifted through by scavengers.

Eddie’d taken their split-up in stride and turned that to strut, returning to Thornford decked out in cast and sling and a cluster of honeys who hung upon him while appending their names and numbers to his plaster-of-Paris. “Write with a fine point, now! Leave a li’l room fo’ the next gal in line!”

Nonique had neither clustered nor queued, yet her path got crossed again and again by the Fair Catch strut. Each time he gave Sweet Thing another ear-to-ear elastication, while his hangers-on shot eye-daggers at Nonique from top to toe.

LaVinia had shot her a couple of eye-thumbtacks before relenting for Thanksgiving and best-friendship’s sake. “You just lucky I been sick—else I’da scooped him up. You even luckier I got well enough in time to eat. Okay, girl, I help you catch him, but only if—IF—we hook me up with one o’ his better-lookin’ varsity buddies. Don’t matter which sport, but he gotta be at least twice—TWICE—as funktastic as George Sumpter!”

So they set out to bag themselves a couple of wild turkeys.

LaVee quickly set her sights on Damon Ingram, high diver on the Raven swim team (“Ooooh, don’t he just fill them trunks!”) who’d been known since wading pool days as “Dook.” Some said this was as close to “Duke” as he could spell; others attributed it to his eccentric hygiene, though LaVee argued that he was cleansed by chlorine and had precisely the right degree of macho aroma.

LaVee being LaVee, she soon mapped out Dook’s and Eddie’s daily routes through and around Thornford, locating points where these could be easily intersected by herself and Nonique. When all four converged on certain spots at certain times, LaVee would wield her enticing rod-and-reel while Nonique stood by, tongue-tiedier than ever—and let Eddie Ray Anderson handle the palaver. He had to keep his cast on till Christmas, but nothing fettered his tongue or lips or gravelly voicebox as he brought them to bear on susceptible Nonique. Other girls continued clinging to him as a Fair Catch; yet he seldom let slide a chance to bear down on Sweet Thing and coo a few sly suavities into her hotly-blushing ear.

There were only four-and-a-half downsides to this delightfulness.

The first-and-a-half was that neither Eddie nor Dook made any move to actually ask the girls out, for even so much as a 7-Eleven Slurpee. And if they ever did, the odds were zilch for getting parental permission; their mothers had dictated “No date-dating till you turn sixteen,” and as far as Taw was concerned, “You ain’t goin’ out with any boy till you been married sixteen years!”

Secondly, Rumah Myers kept parading around the periphery like the aloof majorette she was—or the voodoo hexcaster people said she might be. Some whispered that Rumah’d caused Eddie’s injury by skewering an effigy she’d made out of chicken bones. You could hear the Witches’s Chorus from Macbeth whenever Rumah’s roving thundercloud obscured the horizon.

Thirdly, this didn’t intimidate LaVinia or stop her from telling Eddie (on Nonique’s speechless behalf, when Rumah was within earshot) that because the Smiths came from Little Egypt, they were therefore gypsies and endowed with uncanny powers of their own. Hence the Rebounder’s expertise at basketball and Nonique’s on the oboe: “Y’ever hear her play that thing? She can blow up a storm, and don’t need no scraps from a chicken bucket t’cast her magic spells!”

“(Veeee...)” shrilled Nonique.

“I c’n dig it,” nodded Dook.

“’She was a gypp-see woman... she was a gypp-see woman,’” sang Eddie (à la the Impressions, not Brian Hyland).

And out on the periphery Rumah Myers went “rrrgggh”—or whatever noise a tigress makes when gratuitously flouted.

Fourthly and finally: the Band’s marching season had gone on hiatus (to Winthrop Eshton’s desolation) and concert season was in full swing, with incessant rehearsals for the annual holiday program. These obstructed Nonique’s intersecting with Eddie Ray, till LaVee contrived one of her clever workarounds.

Twenty-five years earlier, Mr. Lynn had composed a musical about the Three Magi titled Christmas Caravan: A Kismet Carol. Every December he foisted excerpts from this opus on Thornford High, with varying degrees of appreciation. (The dancing camels were always a hit, though far more students auditioned for their front halves than their back.) It included all due reverence and adoration of the Christ Child (which needed to be soft-pedaled in a mid-Seventies public school) and had a soulful oboe solo for Nonique to perform when Yazmin, daughter of the Magus Melchior, relinquished her precious frankincense to own a Deity nigh.

LaVee (God bless her everyone) lured Eddie and Dook into the auditorium long enough to hear Nonique practice this, pouring her heart out through her embouchure, imagining each note was a strand in the romantic lariat she hoped to sling around Fair Catch’s rich-slow-deep-gravelliness.

Then came that exultant moment by the metal shop, where just Nonique encountered just Eddie—no LaVee, no Dook, no cluster of hangers-on, no Rumah darkening the skyline—and was presented with a shiny-bright split-ring washer as if it were costly jewelry:

“My Christmas gypp-see woman... my Christmas gypp-see woman...”

Chords crashed like breaker waves on the beach of Vernonique’s devotion, sweeping her away from there to eternity.

Or what might’ve been eternity had winter not descended with a vengeance: the harsh winter of forty-three straight days below freezing, twelve of them below zero, and the Lake itself nearly transformed into an iceberg.

Rumah Myers’s brother Maurice got stabbed on Christmas Eve, officially while resisting a robbery at the Dow-Dee liquor store their father managed; though rumor had it that Rumah did it herself when Reese tried messin’ with her. However it happened, Rumah was in need of what Dennis Desmond would call “CONdolence and CONsolation” and so drew Eddie Ray back into her web. By New Year’s Day they were fully reconciled, and Fair Catch was off the free market.

Nonique had scarcely a minute to bemoan this before Grandma Cat suffered a bad stroke that turned much worse when the weather delayed her being rushed to the hospital. Not that Cat would admit to any need for admission there; in her mind, the doctor’s diagnosis was plumb wrong, making her fritter time away in a convalescent bed. Her certainty about a swift return home was contagious, at first, thanks to apparently unimpeded vigor:

“It still snowin’? You better not tell me you been shovelin’ it, Abram—get that Jenkins boy to clear the driveway—make sure he salts the front steps good—I don’t wanna slip on ‘em the moment I get home. You eat right last night? What you fix for dinner?”

“Bacon and eggs,” said Grandpa Bram.

“Bacon and eggs! Better not be ruinin’ my kitchen! Where you drain the grease?”

“Grease?”

“Don’t you tell me you poured it down the drain!”

“Course not, honeybunch! Sopped it up with a piece o’ toast.”

“Okay—that does it—get my clothes—I’m outta here—someone gotta save your fool arteries from hardenin’—”

Cat tried to fling off the bedcovers with her unaffected arm... and couldn’t. The next day she sounded almost as rambunctious, but a trifle less coherent; and each day after that was a further step down into the shadows.

Agitation displaced hardihood. Doctors, nurses, therapists were accused of lying about her condition so they could keep her in the hospital and run up the bills. Husband, children, siblings were rebuked for collaborating. Cat suspected perfectly well that Vernon Smith, not Medicaid, was picking up the tab for week after week in this semi-private room, and she wouldn’t stand being beholden to that man, do you hear?

The thing of it was, she could no longer stand even when aided. Increasingly she could not make herself understood. Inexorably she melted away, degree by degree, as the once-harsh winter was starting to do outdoors.

Before long the only ones able to comprehend Cat without difficulty were her youngest sister Aunt Duz, who taught sign language to deaf children; her old friend Bessie Higden, Aunt LeeLee’s mother, who was an experienced social worker; and Nonique, on the purely-a-Curry wavelength.

Glance from the eye with the undrooping lid. Press of the hand whose fingers could still return a squeeze. Exchange of words without recourse to phonetics.

Don’t you be running yourself ragged, child.

I’m not, Grandma.

You look like you are. Don’t want the both of us here in this fool bed.

I’m too big to fit in that one with you anymore.

That’s right, you’re a big girl now. But don’t be thinking you’re a grown woman yet.

Not even sometimes?

I’ll tell you when you are. Until then, no more wearing yourself out.

It’s just this awful weather. What they call cabin fever.

Tell me about it—stuck in here. Better yet, play me “From All That Dwell.”

Nonique was permitted to bring her oboe to the hospital during visiting hours and play it in Cat’s room, so long as the other occupant (latest in a succession, all of whom groaned in their sleep) didn’t object. An audience would gather around the doorway (medical staff, other visitors, ambulatory patients) to hear the miniconcerts of what Uncle Babe liked to call “airs and graces—hymns and prayers. Get it? Get it?”

|

From all that dwell below the skies Let the Creator’s praise arise Let the Redeemer’s name be sung Through ev’ry land by ev’ry tongue |

And till that cabin fever breaks (thought Nonique) don’t spill the beans about my heartaches.

In eighth grade she’d read a scary story about how silent secret snow made the world grow smaller and smaller, like a flower shrinking backward into a tiny cold seed. Such was Nonique’s life that bitter winter: an ever-abbreviating cycle of rise without shine, frost without thaw, means without end. Home, school, hospital; or home, church, hospital; or home, Mr. Nik’s, hospital. With only dribs and drabs of awareness of what was going on beyond that cycle. Being cut some slack for this by everyone, even LaVinia who usually demanded complete attention. Glimpsing the Shady Man in just the loges and bistros of Slumberland, unvexed by voodoo hexes yet vanishing at the next rise-without-shine.

|

Eternal are Thy mercies, Lord Eternal truths attend Thy word Thy praise shall sound from shore to shore Till suns shall rise and set no more |

A time fast coming for Catherine Curry Randle.

Enough of her old armor plate remained intact to threaten she might linger in an interminable vegetative state, like Karen Ann Quinlan. Yet as Cat herself would’ve put it, “The Lord knows me better than that”—and she breathed her last shortly before Easter and her sixtieth birthday, when the thermometer took a typical Citylandish leap from below freezing up into the eighties.

|

We are (we are) / climbing (climbing) Jacob's ladder / soldier (soldier) / of the cross... |

With Cat’s grip gone from the reins, her family faltered to a halt. Patriarch Ezekiel was Big Zeke no more, but a wizened old mutterer-about-undertakers who’d buried three wives and now his eldest daughter alongside two of them. Grandpa Bram could not bear to live alone in the Ferndean Gardens townhouse and so bunked with bachelor Uncle Babe, both of them swamped by melancholia. Bessie, LeeLee and Miss Fanny Hooker took it upon themselves to divvy Grandma’s effects, acting on instinct for who Cat would’ve wanted to inherit what. Nonique received a gold locket that she was afraid to wear outside her blouses, but felt uncomfortable dangling beneath them.

“Under’s best—leastway if the chain snaps, yo bra’ll catch it ‘fore it falls,” observed LaVee, regarding the extra cupsize Nonique had gained over the winter.

“(Not so loud,)” went Nonique, hugging her oboe to her accentuated bosom.

“Girl, we’re here t’be heard!”

They were at a rehearsal for The Wiz, Thornford’s Spring Musical, in which LaVee’d been cast as one of the Munchkin/Winkie chorus. She’d wanted to be a Funky Monkey till hearing they wouldn’t be flown on harnesses over the stage; Thornford couldn’t afford the insurance coverage.

Snobby-conceited Rochelle Briggs had won the role of Dorothy, which was only slightly less preposterous than Diana Ross’s stealing it from Stephanie Mills for the upcoming movie version. Not that it’d matter, since Thornford’s show was certain to be stolen by Marquita McLeod as Evillene the Wicked Witch. That part seemed more suitable for Rumah Myers, but she and the other majorettes were performing all the standout dance numbers, with Rumah turning the Tornado Ballet into a Striptease of Seven Veils (off a disco leotard).

Addie Mae Anderson would’ve been perfect as Addaperle the Feelgood Witch, if the Drama Club had been able to raise enough funds to rent her a giant teleprompter. She was content to stitch together wondrous concoctions as the show’s costume mistress, taking “bag-lady boogie” to a theatrical level. Meanwhile the stage crew enlisted Eddie Ray to handle the switchboard, he being almost as proficient with toggles and rheostats as his twin was with needle and thread.

“Say the word and I’ll be dimmin’ the lights!” he proclaimed at every rehearsal, leering down from the backstage catwalk—

“You listening t’me?” LaVee broke into Nonique’s reverie, cutting her no more slack. “High time you quit that sleepwalking.”

“Not s’posed to wake up sleepwalkers,” murmured Nonique.

“Well I got to, don’t I? Ol’ Tippins be calling us any minute now—”

“Winkies front and center, please!” crackled Mrs. Tippins over the P.A. “All Winkies, on the double!”

“What I tell you?” sighed LaVee. “Bet they don’t treat dancers like a bunch o’ cows on Soul Train!”

Off she mooed for another run-through of “Brand New Day,” while Nonique joined the Concert Band in front of the stage to provide accompaniment. As the lone oboe, she played the A-note for the Band to tune to: a task she previously took pride in, but now was just another trancelike step taken through another somnambulistic afternoon.

It wasn’t as if she hadn’t tried to perk up since Grandma’s funeral. Everyone kept urging her to do so, even the chorus onstage: Just look about! / You owe it to yourself to check it out!

Easier sung than done when you kept stumbling and fumbling through opaque darkness, brushing against unseen things that clung to your hands and arms till you were afraid you’d be pinioned, caught in a winding sheet, shrunk down to that tiny cold seed—

—as Mrs. Tippins whistled the Winkies to stop after stop and Mr. Lynn had the Band do likewise, going back and doing over and we’ll-stay-here-all-night-till-you-get-it-right which wasn’t apt to happen (the staying if not the getting) while you persevered, your clung-to arms outstretched, trying to sleepwalk past the unseen and find an exit or at least some illumination—

“Kill the lights,” ordered Mrs. Tippins, her voice rough with disgust. “That’s enough for one day. Everybody out.”

LaVee promptly swooped off the proscenium—who needs a harness to fly?—and, giving Nonique an airy wave, sprinted up the aisle out of sight. Nowadays she was going with (as well as after) Dook Ingram, and had to hustle to make the most out of Friday-night-until-curfew (or-as-late-as-can-be-gotten-away-with).

Nonique remained behind to mechanically dismember her oboe. Swab out its joints, blow out its reed, pack these in their separate cases, latch them glumly shut—snick, snick—

“Allow me, Sweet Thing,” went a gravelly unravelly voice.

Classical masterful laying-hold of her instrument with one hand, as the other arm (long since freed of plaster) draped itself over her shoulders, causing her internal candelabra to undergo spontaneous combustion.

“Might I be transportin’ you anywheres?”

“W-what about...?”

“Addie? She off to one o’ her ‘quiltin’ bees’—and’ll be there makin’ outfits fo’ Poppies till they put her to sleeeeeeep—”

“No, I mean...”

“You twistin’ that purty head ever’ which way lookin’ fo’ Rumah the Tornado? Don’t worry none ‘bout her—she won’t be showin’ till my next payday.”

Eddie had a part-time job at the Riversgate Conoco station, which didn’t generate enough income to keep Rumah satisfied on a full-time basis. In the meantime she was stepping out with Billy Carter—not the new President’s beer-swilling brother, but a senior on the Thornford track team who preferred fortified wines like Ripple.

Be that as it may, Nonique didn’t feel Tornado-safe till she was buckled into Eddie’s elderly Cutlass Supreme with all its doors locked, and they’d driven far enough away that the school could no longer be seen in the rearview mirror.

“Come on ‘n’ ease on down, ease on down the road,” crooned Eddie before cranking up Studio 107 on the car radio—and, like the SuperAfro dude in Car Wash, lip-syncing Rose Royce’s “I Wanna Get Next to You.”

Well, you have—and you are, thought Nonique between poundings of her heart. So what happens next?...

A segue to Earth Wind & Fire’s “Can’t Hide Love,” and Eddie’s idling at a red light to strike up a cigarette.

“What brand you smoke?” asked Nonique, thinking Could you ask a more idiotic question?

“Newports. ‘Bold ‘n’ cold!’ Want one?”

“Oh no thanks.”

“They menthol—good fo’ the throat.”

“Um maybe so but I gotta save my lungs, y’know, for the oboe...” Idiot! Idiot!

“That’s cool.” (As Kool & the Gang chimed in with “Open Sesame.”) “You right to take care o’ yo’self. And to look out fo’ that Rumah Myers. Her ‘n’ me, we was lazin’ ‘round this one time when a moth flies inna her room. She screech ‘That’s the devil been chewin’ holes in my clothes!’ ‘n’ jumps up to catch it. Knockin’ stuff over as she chases that bug—chair, lamp, perfume bottles—then she grabs hold of it, ‘n’ takes this pin looks big as a chopstick ‘n’ impales that po moth like she was giggin’ a frog! She watches (and makes me watch) till its wings quit beatin’—then sticks that damn pin with that dead bug in her hair.”

Slow smoky-clouded exhalation out the Cutlass window.

(“Get down with the genie!” commented Kool & the Gang.)

“Heh heh heh heh...” went Eddie. “Now if I caught me a moth, I woudn’t do no worse’n stick it down some purty gal’s neck”—demonstrating with the back collar of Nonique’s floral print blouse.

Yeeeep!! by Nonique.

“Now what we got here?” inquired Eddie, his finger snagged. “Feels like you got sump’n heavy hangin’ on this here chain—heavy ‘n’ hid away. Wonder what it could be?”

“Don’t!” went Nonique, clapping an arm across her bustline as if he’d gone straight for her bra hooks.

“Oho—it’s like that, is it?” said Eddie, cruising the Cutlass to a halt along a side street. His snagged finger gently (yet irresistibly) traced the chain under the collar around to the throat, and there hoisted up its pendant accessory till it glittered in his hand. “My oh my... where you get this?”

“From my Grandma,” wobbled Nonique.

“Well, that’s nice—real nice. Par-tic-u-lar-ly since you didn’t get it from no other boyfriend.” He propped the locket on her bosom-shelf with careful exactness, and snuffed his Newport in the chockablock ashtray. “Why don’t we straighten our legs a little?” he suggested, sauntering out and over to open the passenger door like a courteous gentleman.

It seemed rude to stay seated inside.

He’d parked the Cutlass beside a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire, beyond which lay vast acreage belonging to the water reclamation plant. No one was nearby except a few seagulls wheeling overhead, and a row of crows perched companionably on the fence. Lounging against it below the crows, Eddie used a thumb to dislodge teardrops from Nonique’s tremulous lashes.

“Ain’t gonna cry on me, are you?”

“(Not ‘less you make me.)”

“Now why you think I ever do a thing like that, Sweet Thing? Course, you might cry fo’ joy if I give you a fine bracelet to match that nice necklace.”

“(Thought you said you got no money.)”

“That’s cause I invest it, see? Like a moe-gool, fo’ a ree-turn—such as one o’ these” (encircling her waist) “or one o’ these” (drawing her to him) “or one o’ these” (pressing his tobacco-tinged mouth to her Fashion Fair lipgloss—)

thunder thunder thunder stormed Nonique’s circulatory system as he tightened his Fair Catch embrace, till they were mashed together and the locket dug into both of their chests.

So it began.

The spring fling that would become a flung sprung.

Nearly all of it (but not enough, in the end) done on the sly.

Vernonique realized from the get-go that she was the Other Woman in a triangle with Rumah Myers—or a quadrilateral, if you included Billy Carter—unless it was a pentagram, factoring in the Voodoo Devil. Whichever way you outlined the relationship(s), discretion would be the greater part of survival.

LaVinia knew all about it, of course, and teemed with ploys to facilitate matters. Addie Mae knew too, wringing her hands (when not busy at the sewing machine) as she counseled noncompliance with Eddie Ray’s tendencies. And then, during another take-five at another Wiz rehearsal, an additional interested party reared an unwelcome head. Winth-ROP Eshton, who’d never shown the least concern for Nonique’s wellbeing before now, executed a double-left-flank-hut to block her path and hiss into her face: “(What are you doing? What do you think you’re doing? Have you gone and lost your mind?)”

“Wh—” went Nonique; but Winthrop had right-oblique-hutted off to the backstage ladder and was clambering up it to the catwalk. There he confronted Eddie Ray—who had on a neon orange jogging suit that outshone the spotlights—and, while keeping his hiss low, demanded to know Eddie’s intentions vis-à-vis Nonique.

“Guess you could say I’m a mew-chew-ull friend o’ the fambly,” said E.R., emphasizing the B to madden Winth-ROP, who was a stickler for clear enunciation.

“Well, you just... you just... you just... leave her alone, that’s all!” he stammered. “If you know what’s good for you!”

“I jus’... I jus’... I jus’... always know who’s good fo’ me,” remarked Eddie from on high. “Run along now, li’l freshman—yo trombone’s tootin’ fo' you.”

Winthrop descended the ladder and harch-harch-harched back to hiss “(You see? You see? I am SO disappointed in you!)” into Nonique’s dumbfounded face, before falling out of formation and retreating from sight.

“What was that?” Nonique asked LaVee.

“Looks like you got a secret admirer.”

“Aw, noooo... not him.”

“Sure looks like it. Mind if I don’t get jealous?”

That task was speedily volunteered for by Marian “Midget” Pettis the glockenspiel player, who’d borne an unrequited crush on Winthrop since first grade. LaVee theorized that Midget had been dropped on her head as a baby, accounting for both the crush and her lack of height. Now she peered up at Nonique with wordless reproach; and the pentagram was enlarged to whatever you called a plane figure with seven points. (Heptagon? Heptazoid? Hepzibah?—good name for the Voodoo Devil.) Making it even trickier to keep Nonique and Eddie’s intersections on the QT. His neon orange jogging suit didn’t help, either.

As The Wiz edged on down the road to and through what Mrs. Tippins, with morose optimism, called the worst dress rehearsal in Thornford Drama Club history, Nonique yearned for a cyclone cellar in which she might hide from crackpots and lamebrains. When she wasn’t being mutely accused of love-larceny by Midget Pettis, her heels were getting dogged by the abnormally hamfooted Winthrop. Then she had to withstand LaVee’s goading her to do-this-with-Eddie, try-that-with-Eddie, while Addie Mae lobbied for hindrance and restraint, and Teri Rhett (the chummiest of the Band’s fifteen clarinets) kept asking “What’s the story with you and Fair Catch?”

All of which was preferable to the goings-on and gettings-down in Slumberland.

Where once Nonique had cozied up with the Shady Man, she now could only see him at a lengthening distance, unable to be followed or called back, till she was abandoned to stumble and fumble again through clinging obscurity—before brushing up against Hepzibah the Voodoo Devil who was armed with a pinion bigger than a chopstake and set for pointedly blood-red impalement—

Awaking to circulatory thunder thunder thunder, night after night after night...

“Don’t let no bad dreams bother you,” soothed Eddie Ray. “Do what I do—have yo momma make you a glass o’ warm milk fo’ you go to bed. Course now, there’s other things you can do at bedtime that’ll give you a good—sound—sleep... heh heh heh heh...”

On that subject he was never at a loss for words, or moves, on unfrequented sites around Riversgate where their intersecting could take place. Besides the fence by the reclamation plant, there was a quiet corner behind the auto salvage yard; an odd little grove out back of the Full Gospel Pentecostal Church; and various hidey-holes off Deliverance Road, which wound through semigreenery between the Expressway and the River.

There’d been an assembly during Black History Month about how Deliverance Road got its name from being one of the “stations” on the Underground Railroad, where escaped slaves were given safe haven by abolitionists (like Joshua Douser of the original Douser Dell) en route to freedom in Canada. However, this inspirational tale clashed with present-day Deliverance Road being a notorious lover’s lane—plus a reminder of that backwoods-redneck movie from a few years ago, so all the class clowns began to make “Dueling Banjo” noises and squeal like a pig.

Nonique continued to frequent these hidey-holes as The Wiz came and went. Maybe too frequently, given Eddie’s mastery at manipulating causes and effects; particularly on a Good Girl who meant only to allow the milder liberties to be taken, as she had with Reuben Burns (and a few of those had been inadvertent). But E.R., unlike Reuben, could see clearly how to breach her barricades step by step; and for him it was as easy as riding up an escalator. Or more aptly an elevator, since he could play upon Nonique’s buttons as if they were switchboard rheostats.

Down the garden path she was led through that merrily-rolling-along month of May. In short order they advanced from full-frontal hugs and Franco-American kisses to fondling (her) through fabric, to liberating the upper torso (hers) from Lycra, to hickeyfication of her liberations (shunting Grandma’s locket aside) and then to tentative fondling (him) through fabric. All of this was accomplished without high-pressure tactics on Eddie’s part—unless you counted whatever mesmerizing gambit he employed to make Nonique be the sensual aggressor and take the backseat initiative, time after time.

“Go ahead, Sweet Thing,” he would sigh with feigned capitulation. “Do with me what you will!”

And she did, again and again. Eddie might play upon her blouse-buttons, but it was Nonique who undid them. He might slide an inquisitive fingertip into the front of her bra; she was the one who reached behind her back to unhook it. He might raise his Fair Catch hand in benediction on her emancipated bosom; she’d grab that hand and put it to touchy-feely work. He might pucker his rich/slow/deep/gravelly mouth; she’d cradle his head wet-nurse-style while it sought sustenance and nourishment.

Then Nonique would go to bed (alone) after drinking the prescribed glass of warm milk; and before her nightly brushup against Hepzibah’s chopstake, she would re-enact that day’s latest double-daring-do. Sometimes writhing with shame; sometimes thrilling with bliss; always boggling at her own audacity. Were it not for the thankfully hidden bosom-hickeys, she’d’ve been inclined to chalk it all up to fantasization.

Yet how could she—she—be taking such steps forward, for real? Steps down the garden path and through the gates of the Carnal Chocolate Factory, to carry on like Augustus Gloop and Veruca Salt and Violet Beauregard combined? Her face (and chest) burned at the thought; never before had she given way to covetous gluttony. Now she was involved with embouchures on a whole different scale—one that entailed much heavier breathing, and a lot more saliva.

“What is that man doing to me??”

“Don’t you know?” asked LaVee as she painted Nonique’s toenails Fashion Fair Foxy Pink.

“If I did, would I ask?”

“‘He’s yo boogie man, that’s what he am, here t’do whatever he can,’” sang LaVee. “Hold still, girl! This is my good polish!”

Restive shifting by Nonique, with gaze-aversion from the swim team photo (blown up to poster-size and taped on LaVee’s bedroom wall) of Dook Ingram in anatomically-correct trunks.

“Do I not come from a medical background?” LaVee had sassyfrassed when Aunt LeeLee’d objected to this being hung.

“So you’ll put these up beside it,” LeeLee’d replied, adding really gross diagrams of the human muscular and skeletal systems to the same wall.

Imagine how the Smith household would react if Nonique dared replace her gallery of favorite oboists—Ray Still, Harry Smyles, Evelyn Rothwell—with beefcake Polaroids of Eddie Ray Anderson in the backseat of his Cutlass Supreme—

(Ohhhh sweeeet motherrrr...)

(Her imagination never used to go to such fervent lengths...)

“Hardly need t’turn on a lamp in here, you blushing so bright,” smiled LaVee as she started on the other foot.

“Quit tickling!... You think I wanna have these ‘thoughts’ running wild through my mind?”

“Face it, girl: you always been a thinker, not a doer. Now yo bod’s finally catching up with yo brain, and about time too. Perfectly natural—no need t’freak. Would be, if you blushing so bright over ol’ Winth-ROP—”

“Will you hush?”

It wasn’t bad enough to behave like a Bad Girl, knowing she should reject impulses to trespass on personal private property (his and hers) instead of sizzling with possessive anticipation and palpable gratification. No: along with all that, she had to steer clear of Winthrop Eshton. Which was nothing new, since he’d never hesitated to shoot off his longwinded mouth about recital precedence or the superiority of marching bands. These days, though, he seemed to have trouble putting two words together without spluttering. Worse yet, too many of those words seemed to center on his being infatuated.

With Nonique.

She’d been crushed on by plenty of boys—first for being her father’s daughter, then for prettiness enhanced by bashfulness and blossoming shapeliness. Not one had been worth reciprocating (Reuben fit more into a friend-with-benefits category) and LaVee’d told them to buzz off, occasionally reeling a crusher in for her own fun before throwing him back.

Winth-ROP, however, was unbuzzable as well as unbearable. He’d show up at the most inopportune times, ahem-ing and harrumph-ing without managing to clear his throat, grimacing at Nonique’s brow or chin but never quite into her eyes as he rang disjointed changes on his earlier What do you think you’re doing? query.

“Do you mind?” Nonique would huff at him.

“Do YOU mind being made a fool out of?” he’d try to reply, after apparently swallowing an entire hardboiled egg unchewed.

“What business is it of yours?”

“Funny business! And I’m here to tell you—so listen good!—there isn’t anybody, not anybody who wouldn’t laugh themselves sick if they knew what you’re getting up to—or should I say getting down with?”

“Get away from me!” Nonique would request; and LaVee (if present) would add something like “Yeah, go ‘n’ empty yo spit valve over someone who deserves it!”

“You bet I will!” Winthrop would vow, sounding as if that hardboiled egg was lodged inside his windpipe. “I’ll just have a word or two with your Tin-Eared Woodman” (clenching one fist while shaking the other) “and maybe teach him a thing or two about where and how he can slide his oil!”

Away he’d lurch with none of his parade-ground precision; leaving Nonique to seethe and LaVee to scoff and Midget Pettis to quaver “If he gets beat to pieces, it’ll be on your two heads!”

“None o’ this be happening if you be woman enough to work yo wiles on a man, or even a Winth-ROP!” LaVee would sneer; whereupon Midget would trot off in unrequited tears, making Nonique feel even worse.

“You didn’t have to tell her that.”

“You want her hanging round all afternoon, giving us the stink-eye?”

Well, no. This heptawhatsit was becoming far too complicated for Nonique. She felt relatively sure that Eddie wouldn’t fight Winthrop unless he (Winthrop) came after him (Eddie) with an axe. Yet Eddie was liable to bombard Winthrop with witticisms about being a li’l tromboner who played upon his own buttons, till he (Winthrop) did come after him (Eddie) and get himself beaten to pieces (axe or no axe). And then there’d be a ruckus, and Midget would fuss it up further, and Rumah Myers would hear about it, and Nonique would be constricted more tightly than ever by this heptawhatever—

—when all she craved was an exclusive undivided intersection with Eddie Ray. And not just another huggery-muggery backseat miniliaison, either. There had to be more to romance than erotic angling, no matter what LaVinia thought or how Eddie maneuvered.

You couldn’t hash such things out with a parent or teacher or school counselor or clergyman. The only approachable adult Nonique knew was Duz Curry, technically her great-aunt but really her surrogate big sister, and one who’d savored La Dolce Vita. “Oh, that Delores,” Grandma Cat had always called her (with a sigh and shrug and headshake). Freda called her “Acksh”—partly from years of saying “Actually she’s my aunt” and partly from Duz’s colorful career as an Action Girl.

In the late Sixties she’d cultivated an Angela Davis Afro and attitude, her militancy disturbing Big Zeke and her older siblings who thought it foolhardy to openly antagonize white folks. Duz had simmered down (politically) since then and now resembled that Get Christie Love! actress who’d joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Duz opted instead to learn sign language and have a quickie affair with her Caucasian instructor, whom she (with voice and hands) cheerfully called “Honk.”

(Oh, that Delores!)

Nonique arranged to interview her about ASL for a Thornford project. After taking many distracted notes on signing and special ed in Duz’s Bronzeville flat, she gingerly broached the subject of breaching barricades—and nearly fainted when Duz pressed a fistful of condoms into Nonique’s petrified hands.

“But—but—but—but—"

“I know, honey, and here’s hoping you won’t need ‘em for a long while yet. BUT—don’t you ever let a man take that last step with you ‘less he’s got one of these on. And don’t take his word for it, either—you watch while he puts it on (try not to laugh) or better still, you put it on for him, they almost enjoy that—”

“Aunt DUZ!!”

“I know, honey. Just think of ‘em as insurance premiums.”

To be hidden in the concealed zipper-pocket of the fancy tampon pouch (warranted to scare off meddlesome little brothers) that Duz also gave her, as an early birthday present.

Nonique barely survived the El ride back to Riversgate, dead certain all the other passengers could tell her purse was overflowing with prophylactics. Which would have to be kept secret even from—especially from—LaVee, who’d say or do Lord only knew what if she found out about them. And the exact same could be said for Eddie... at least for the time being. Until later. If not sooner. But then when?...