Chapter 37

After School Specials

On the day that Robert Peary set off on his final expedition to find the North Pole, a child was born three thousand miles south of that target. The child’s father wanted him to be christened John Logan Agate Jr., but the child’s mother prevailed and named him after the Reverend Fenster Mouple, composer of torpid temperance hymns.

From a very early age this child would introduce himself and sign every document as “F.M. Agate,” hinting the initials stood for Ferdinand Magellan. He yearned to become a great explorer like Peary, blazing trails into terra incognita by land or sea or avant-garde airplane, winning glory for his family name (if not first or middle) on some distant frontier or battlefield. While still in kneepants, he prayed that the Great War might last till he was old enough to enlist and go Over There. The closest he got was to be dubbed “Major Domo” by his classmate Chester Brockhurst (already exhibiting trenchant wit as a fifth-grader).

That title stuck to F.M. through graduation from Vanderlund Township High School in 1926. Nor was he able to escape homebody status for the next three years, during which he commuted daily to the Normal College down in The City. Male enrollment there was vastly outnumbered by co‑eds, some of whom looked with favor upon F.M.; yet he was duty-bound to return nightly to Vanderlund and tend to his widowed mother, who frequently smelled F.M.’s breath to make sure he was adhering to the blessed precepts of Prohibition.

At twenty-one he began his teaching career, not in an exotic foreign clime but unexciting Green Town, which may have produced Jack Benny and Ray Bradbury but held little charm for F.M. Agate as he eked out subsistence during the Depression. Living on scant rations in cheap boardinghouses, he devoured each month’s National Geographic from cover to cover and squirreled away nickels for the picture show. F.M. enjoyed extravaganzas that were set abroad—Stanley and Livingstone, shot on location in Africa, was a particular favorite—and treasured the travelogue newsreels that transported him (if only for a few minutes) to faraway realities.

As opposed to near-at-hand banalities, in which obstinate Fate kept him rigidly rooted.

Though among the first to volunteer for service after Pearl Harbor, F.M. was disqualified for having poor eyesight and flat feet. He did get drafted into administrative duties at school, becoming an assistant principal by V-J Day, but could venture no further from The Cityland than to attend a former colleague’s funeral outside Kenosha.

In 1951 he returned to VTHS as deputy to Hamilton Exelby, who’d begun to act more like Teddy in Arsenic and Old Lace than the Hero of San Juan Hill. F.M. was delegated to host his Class of ‘26’s silver reunion, though its keynote address was delivered by Chester Brockhurst the belletrist (“I prefer the term ‘belittler’”) who’d attended Princeton and Yale (“not quite simultaneously”), freelanced for College Humor and Weird Tales (“hard to tell them apart sometimes”), worked on the editorial staff of Coronet magazine (“hogs aren’t the only things that get butchered in This City”), and now wrote a newspaper column that was syndicated nationwide three times a week.

“My proudest boast,” he told the assembled Class of ’26, “is that I’ve never bought a copy of The New Yorker. I will plead guilty to having read it over other people’s shoulders.”

[Laughter] from Vanderlund alumni.

None, though, from F.M. Agate when Brockhurst profiled the reunion’s host in a column as “my old chum Fenster Mouple the Major Domo, whose geography lessons possess the vividness of a chalkboard March of Time. ‘He almost makes you believe he can see what he’s talking about,’ a dimple-cheeked bobby-soxer informed me.”

Hard and cold did Mr. Agate become after this waggery hit the press. He kept his backbone ramrod-upright; a military moustache embristled his upper lip; and students began to believe he really had been a high-ranking officer in some armed force or other. Being sent to “the Major’s” office was seen as a stroke of disciplinary doom.

Thus armored, he took part in the Coup of ’53 (when old Ham ‘n’ Eggs got put out to pasture against his will) and assumed the mantle of VTHS Principal, pledging to restock the faculty along Eisenhowerish lines, cutting out deadwood without allowing any rotten pinkos to sneak aboard.

After three years of such overhaul, Mr. Agate interviewed applicants for an entry-level position in the Social Studies department. He was handed impeccable credentials and references by Miss Shirley Ewing, who had red hair and green eyes and an arresting resemblance to young Greer Garson.

(“Shirley Ew-jest,)” muttered Mr. Staffel the Social Studies chairman, who thought no young women should be teachers unless they were the stringy schoolmarm stereotype.

Mr. Agate, however, was whisked back to 1939 and the first time he saw Goodbye, Mr. Chips. How achingly he’d longed for a Greer-as-Kathie to be there beside him at the Rialto, at his boardinghouse, in his lone lorn bed. Now the perfect candidate had come at last but far too late: she in her twenties, he pushing fifty and her prospective boss to boot.

Miss Ewing’s cool green eyes regarded him with Elizabeth Bennetesque appraisal as Mr. Agate tendered an offer (despite Mr. Staffel’s misgivings) to join the faculty. She accepted, came to VTHS and enchanted the male student body while winning the distaff side’s admiration. Bachelor teachers (plus a few married ones) sought her company for nights on the town, yet she’d only go out as part of a group—and often invited Mr. Agate to come along. At first he’d demur, but Miss Ewing would cajole him into attending a lecture at Lakeside Central on the Suez Crisis, or an exhibit of African masks at the Art Institute, or the Lyric Opera’s rendition of La forza del destino.

One by one the other group members drifted away, leaving F.M. with Shirley and a need to be extremely circumspect about where they might go and what they might do there. Not that she hinted (much less bargained) for preferential treatment, which he wouldn’t have given for all her vibrant expressive allure. He never dared ask what Shirley saw in him. Perhaps it was because she’d lost her father at Guadalcanal when she was only eleven; perhaps because she felt he needed as much nurturing as any callow freshman boy.

In any event she agreed to be his wife, having taken steps to quash any suspicion of workplace favoritism: a friend was going on maternity leave from the ever-expanding Multch school district, and Shirley planned to transfer there if F.M. could convince Mr. Staffel to provide a glowing letter of recommendation.

“One from you might be seen as a wee bit biased,” she told her intended, giving him a Random Harvest-y kiss.

Vanderlund mourned her departure, though there’d be no tragic dying-in-childbirth for young Mrs. Agate; she and F.M. decided they had quite enough kids to look after already. Apart from that, it was a thoroughly Chips-and-Kathie marriage of contrasting attitudes: Shirley, though hardly a rotten pinko, didn’t vote the straight Republican ticket and was in fact an early supporter of John F. Kennedy, while the Major continued to Like Ike (and Dick Nixon, to a lesser extent). He thought it imperative that the United States beat the Soviets in the Space Race; she wished flying to the moon could be done internationally. Yet F.M., after having his lenses gently polished, was able to see eye-to-eye with some of her perspectives: Shirley convinced him, for instance, that there were more promising roles for the Peace Corps than what Dick Nixon called “a haven for draft dodgers.”

Then befell the Pitched Debate of 1963.

That spring Vanderlund elected a new Board of Education, the previous one having worn itself out during a four-year wrangle over whether to build a new West High School for the inlanders, or a district-wide junior high to which shorefolk would have to be bused. Ultimately the latter course was chosen, preserving VTHS as VTHS and not a diminished “Vanderlund East.” Now the new Board had to decide whether to approve an experimental proposal by which a carefully-screened Negro or Negroes (as unplural as possible) would be selected for admittance to VTHS.

Deliberations were held in executive session, behind locked and guarded doors.

Favoring the experiment were Father Phelps of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church; Miss Brandoffer the real estate attorney; and young Mr. Sherman of the Red Cross.

Opposing the proposal were Mr. Beauchamp the banker; Mr. Drexler the insurance agent; and Mr. Peabody the corporate consultant.

Straddling the fence (awkwardly, and not just because he was built like William Howard Taft) was Mr. Horton the School Board President. His grandfather had in fact been Taft’s last Ambassador to Spain, the one who’d arranged Madrid’s financing of the Torre del Oro Fountain in Spanish Castle Square as a grand gesture of hatchet-burial, fifteen years after the sinking of the Maine.

Half a century later there were devout hopes (and harbored doubts) that the current Mr. Horton would be able to achieve a similar reconciliation. Doubts took the lead as Eberhard Drexler spent many minutes discoursing on how this scheme was the thin edge of the Communist wedge, engineered by Khrushchev to reinforce the infiltration of Jews into Vanderlund’s school system.

“Bunk!” replied Miss Emily Brandoffer, who (it was rumored) knew the net worth of everyone in the township and the location of every skeleton, closeted or otherwise.

Mr. Horton, mopping his portly brow, asked if Principal Agate had any remarks to make on the matter at hand.

“I do, sir.”

His inclination had been to line up with the opposition. Not so much behind ranting Mr. Drexler as analytic Mr. Peabody, whose charts and graphs forecast longterm benefits being outweighed by shortterm harm. But a pair of cool green eyes had guided F.M. through a scene almost identical to the one in Chips, when Brookfield balked at hosting a soccer team of slum boys who were sure to be hooligans, leading to “incidents” that would wantonly upset a status quo better left undisturbed.

This sort of trepidation cut no ice with Shirley Ewing Agate. Nor should it with the man she’d fallen in love with, the man who was intrigued by African decolonization and had exchanged cordial letters with the headmaster of a high school in Ghana.

Chips, they’re wrong, you know, and I’m right. I’m looking ahead to the future...

And so was the Major when he rose to address the School Board and later the PTA, the VTHS faculty and its student body, giving each his version of Harold Macmillan’s “Winds of Change” speech:

“This is not Tuscaloosa, nor is it Little Rock. This is Vanderlund, and we shall move forward together into a future that will take us to the stars and beyond. We shall disentangle every knot along the way in a contemplative fashion and tranquil frame of mind, like the good Gondoliers we are, have always been, and will forever be!”

Which persuaded Mr. Horton that a person was a person, no matter Who; and secured his vote for the integration—if only to a token extent—of VTHS.

The first black pupil to enroll was Orson Porter, whose fine husky-sounding name mollified dubious Vanderlundians—if you gotta recruit a colored kid, find one who can play football like Willie Galimore!—till Orson turned out to be built like Sammy Davis Jr. Some students defied the Major and tried to trigger incidents, subjecting “Pullman” Porter to various kinds of badgerment; but many rallied around Our Negro and gave him ovations when he performed “What Kind of Fool Am I” and “Make Someone Happy” in annual talent shows. (A decade later Orson would choreograph the musical Fabulous! in San Francisco, having been a pioneer in more than one field.)

A trickle of other students of color followed in his footsteps; more as the Real Estate Board dealt with Fair Housing by devising Happel Land for their habitat. There were never enough to constitute a “bloc” (such as the Afro-American Movement that occupied the Lakeside Central bursar’s office in 1968) but blacks eventually amounted to almost 1%—if you rounded up—of total attendance. Most, when asked, would state for the record that they were proud and glad to be part of Vanderlund’s venerability.

And why not? This was its Golden Age, when VTHS bestrode The Cityland like an academic colossus. Producing a dozen National Merit Scholars and Finalists each year; making bleachers groan under the grouped-for-a-photo National Honor Society; requiring additional trophy cases to house not just NESTL(É) championship cups in every sport, but county/state/regional awards for music, debate, safety, civic spirit, community activism, and all-around excellence. Vanderlund consistently ranked among the top public college-prep high schools in America, and had no hesitancy about innovation during the tenure of Superintendent Amsterdam (“Call me Dutch”) who seldom encountered a groundbreaking program he didn’t want to implement. New Math, sex ed, team teaching, modular scheduling, relaxation of dress codes and hair-length standards—all of which caused Eberhard Drexler and his ilk to write long blistering screeds to the editor of the Daily Herald.

If truth be told, Principal Agate felt increasingly ill-at-ease among these scholastic novelties. He took a dim view of shaggy hair on boys, miniskirts on girls, and slouching postures on either; remarking that Coach Mort Hordt (RIP) would’ve corrected the latter condition with one swing of his thunderous Board.

Test scores maintained their loftiness, but extracurricular activities reached their peak in 1970 along with enrollment—2,413, of whom nineteen were black—after which the participation tide began to ebb into Seventies apathy. And not just among students but the general population: households with school-age children were starting to decrease, as was Vanderlund’s alacrity to subsidize public education. A levy necessary to cope with inflation did the unthinkable by failing at the polls in early 1973. Discipline became a constituent watchword; the school district ditched “Dutch” Amsterdam and was able to pass a lesser levy later that year, averting a teachers strike; but for VTHS the Golden Age was over.

Mr. Agate, though implored to soldier on, took advantage of turning sixty-five and relinquished his Majority. Mrs. Agate (who at forty-two looked Greer Garsonier than ever) had taken leave of absence from Multch to train for the Peace Corps, and some said she’d also taken leave of her senses; but F.M. jumped on the same bandwagon. Here at last was his chance to blaze a trail into terra incognita (to him, if not its native people) as he and his beloved wife were transported out of theoretical suburbia and off to faraway realities.

From Nairobi the Agates sent a telegram to their good friend Father Phelps back in Vanderlund:

HAVING WONDERFUL TIME GLAD WE’RE NOT THERE

*

Vicki Volester would’ve been happy to say the same when she arrived at school on the Monday after her drive-in debacle with Dennis Desmond.

It was no thrill to poke her head into Room 312 at 8 a.m. and find “Old One-Shot Thanks-a-Lot Untie-the-Knot” already present, looking no worse for wear from his Saturday night standup skinnydip. (He and Rags had been given only a dressing-down—so to speak—by the Emery Ridge police, while Larry Garrigan got charged with ripping off Isabel’s blouse and bra—“in a Pinto!”—along with her purse and shoes.)

Vicki, having taken care to tone down her sex appeal by wearing one of Joss’s baggy T-shirts over one of her own, edged cautiously into the classroom... and Dennis paid her no more attention (whew!) than he did any other girl in First Hour Spanish, except of course Diana Dabney who always bore his brunt.

In the back row, Jenna Wiblitz was bearing with a lump. It looked like a big gray tortoise, reminding Vicki of what Ozzie’d called “that dang upside-down bathtub”—a 1950 Nash Airflyte taken in trade by Diamond Joel, which had squatted in the Lot for years as a conversation piece before finally getting sold for parts.

Could this tubby turtle be Rabbi Pip, here after giving his youngest grandchild a ride to school? No: on closer inspection Vicki recognized the lump as a student named Skinner, who’d been Jenna’s stage crew scapegoat at VW. If anything went missing or awry during You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, Skinner was to blame. Some people even identified him as the Phantom of the Sock-Hop, who dropped that sandbag on Lucy’s Psychiatric Help (5¢) booth; but as Jenna’d said at the time, a competent Phantom would’ve managed to crush Candy Gates as well.

Right now he was lumpily blocking the way to Vicki’s desk as he leaned over Jenna’s with a sheaf of papers, at which Jenna (busily sketching a big gray slug stuck inside a saltshaker) didn’t glance as she said “Tell, don’t show.”

“But if you’d just take a quick look...” whined Skinner.

“’Scuse me,” sighed Vicki, neither loudly nor rudely; so Skinner really had no reason to leap into the air like he did, scattering his sheaf and an armful of other belongings over the back-aisle floor.

“Butterfingers!” went Jenna, translating that as the first bell rang to “¡Manazas!”

Vicki, with another sigh, plopped her own things onto her desktop and stooped to help Skinner retrieve copies of Star Reach and Heavy Metal and The Silmarillion, plus glossy autographed headshots of Pamelyn Ferdin and Maggie Cooper from Space Academy.

“Um... yeah... so...” went Skinner, backpedaling toward the door. Out of his gray turtleneck protruded an incongruous pigeon’s head, ashen of hue; it had flat lifeless hair, a sharply pointed nose, and wide eyes round with astonishment. “Wouldn’t she be perfect?” he asked Jenna, before plunging away when she ordered him to piérdase.

“(¿Quién?)” whispered Vicki.

“(Luego,)” said Jenna as the late bell clanged and Señor Banonis called for cálmate.

They were beginning a new unit on Identity and Personal Characteristics, with a focus on direct and indirect object pronouns. The class would again be divided into pairs (Carly Thibert promptly laying hands on Woody Tays) to prepare an oral report, using accurate vocabulary and appropriate illustrations, for delivery in two weeks time.

To Carly (if not Woody) this meant postponing work for the next thirteen-and-a-half days; but Jenna passed Vicki a blotty-ballpoint note that read:

Vicki was gratified by this sign of trust and reliance by her new big sister; all the more so when Lisa Lohe heard about it at lunch and snapped “Some of us still have volleyball practice after school! We’ve got a match at Multch North tomorrow—right, Samantha?”

“Not here,” murmured Sammi, vigilant as ever for glimpses of her Cherry Picker.

“We’ve got personal pronouns to play with,” said Jenna, drawing a bouncy Nosotras.

At 3:30 she and Vicki left school under a garish yellow umbrella with a plastic corncob handle, obtained at last year’s State Fair by Cheryl Trevelyan and traded to “Niblets” for a large stuffed unicorn that Jenna’d received from her injudicious Aunt Sophie. Vicki took charge of this “umbrellow” since the might-as-well-still-be-summer rain was being blown about by a breeze off the Lake, and Jenna (shorter and slighter than herself) was burdened with a hefty zippered art portfolio wrapped in a plastic drycleaning bag that kept trying to skim off and fly away.

“Is he following us?” Jenna asked as they detoured down Steeple for a couple of slices at Deeple’s.

“Is who? You mean Skinner?”

“I don’t mean Leif Garrett.”

“Can’t tell—too many people,” said Vicki, craning her head around at the crowd.

“Safety in numbers,” said Jenna: the anti-Mad-Bludgeoner battle cry.

If true, the pizzeria was a jampacked sanctuary. Space was made for Jenna (as a junior) and Vicki (as her little-sister guest); both being petite, they didn’t need much elbow room, though as per usual every bite of deep-dish pie supplemented their rumps.

The rain ceased as they headed east on Millbank Street, Jenna resuming her commentary (suspended at Deeple’s—“Not while I’m eating!”) about Adlai Stevenson Skinner, aka Egghead aka ASS:

“He’s had a dote on me since fourth grade. That makes seven years of dotage—drab, dull, doltish dotage. Dribbly too, like a sniveling shadow. And this in spite of knowing that I’m ‘spoken for.’”

Jenna was officially in love with Lisa’s older brother Ike, a handsome operatic tenor (much admired by Crystal Denvour) whom many predicted would be the next Jan Peerce. He was currently chasing that goal with singleminded determination (like all the Lohes) at the Indiana University School of Music.

“So Rags was...?”

“A splurge,” explained Jenna. “A girl’s got to work off the pizza-pudge somehow. And find a way to keep the ASS off her ass, if you get my dote-drift.” She dodged a sidewalk puddle while glaring over her shoulder at her bobolink-bottom, then back to see if Skinner was following them now, then over at Vicki through today’s frames: small awning-shaded storefronts. “Bet you’ve had to deal with an ASS or two in your life. Am I right?”

“Oh Gahd... mine was this creepy-crawly paste-eater with cobweb-hair.” Whom Vicki’d spent two whole years happily forgetting about, only to have him bob back into her consciousness twice in the past five days: This is Mrs. Wernie Ball / all in all in all in all. “But that was a long time ago, and far away from here.”

“Count yourself lucky. And enviable.”

Sudden queasy afterthought: “Is Adl—I mean, Eggh—I mean, Skinner—is he any relation to Byron Wyszynski?”

“I wouldn’t put it past him! Is that the paste-eater?”

“No, a different guy I knew at VW.”

“Byron Whatwasit? I thought I knew all the weirdo W’s in town. Assuming this Byron’s a weirdo, and in town?”

“Well he was. We called him ‘Tail-End’—he was always the last one to finish taking tests. Then I had to defend him for cheating on a midterm, at this silly trial we had at VW last spring. Did you guys hear about it?”

“No, we were tied up with a scandal of our own. Gootch Bulstrode was accused of stealing the answers to a big trig test. As if anyone would believe he could’ve passed it without loading the dice.”

“My friend Fiona says there’s cheating rings at schools all over town, even Startop.”

“Startop cuts the cheating stencil—the rest just get blurry mimeographs... Well, welcome to West East Bay.”

Such was the unauthorized name of that portion of East Bay separated from the rest by the El tracks. Which could be seen a couple blocks away, and stirred a much pleasanter memory of Pfiester Park: scurrying like daredevils through the Hagenbush Avenue viaduct, back when you thought a “vy-a-duck” was the tunnel beneath the El.

In West East Bay both sides of Millbank Street were lined with limestone bungalows, the Wiblitzes on one side and the Lohes almost opposite. Lisa’s house was unsurprisingly larger and grander; her father designed prototypes for the American Furniture Mart, and her mother sat (heavily, for a narrow-hipped woman) on the board of the Jewish Community Center. Contrarily, Jenna’s parents co‑owned a low-key optical shop and collected antiques in their spare time, with an occasional mocking observation about “modern décor” to make the Lohes bridle.

Vicki quickly felt at home at 429 Millbank. The Wiblitz bungalow, though clad in limestone rather than salmon stucco, called to mind Gran and Dime’s lox-colored cottage; the same rose bushes lined the veranda here as they had around Gran’s cottage porch, and Jenna’s dormer bedroom had certain similarities to Gran’s time-honored sewing room.

Excluding tidiness: this was a working artist’s studio. Apart from a rumpled daybed in one corner, it had a big drafting table that doubled as desk and tripled as vanity, with an attached accordion mirror; plus a tall floor easel on which sat a shrouded work-in-progress. Jenna’s complete wardrobe seemed to be heaped on the floor of her closet, whose rod was bare of hangers; its shelves, like the half-open dresser drawers, were crammed with art tools and materials. There was paint in tubes and jars and spraycans; paper by the sheet and pad and roll; brushes ranging from fine-haired to whiskbroom-sized; stacks of sketches with various stages of dustiness; and an atmosphere perfumed by tempera and turpentine.

“’Scuse me asking,” Vicki ventured, “but doesn’t this give your folks like constant heart attacks? Mine would freak if I left my bed unmade.”

“They know me better than to think that’d faze me. Besides, my bed is made.”

(Gran would definitely have disputed that. Tuck in those sssseets and smooth them out, Miss, if you do not wisss to sleep on the cowtzz tonight.)

Jenna’s parents were still at work down in The City, but their handicraft was featured on one side of the studio: rack upon rack of unconventional eyewear, including many frames that Vicki hadn’t yet seen at school.

“Aren’t all these glasses kind of expensive, even for an optician?”

“Nope—every one of ‘em has plain plastic lenses. I’ve got 20/20 vision, but wear specs to Make a Statement. Also as publicity for the shop—they pay me commission instead of an allowance. Mention my name if you ever need or just want a pair.”

Another wall was hung with prints and posters, some by The City Imagists; Jenna pointed out June Leaf’s The Salon and Suellen Rocca’s Sleepy-Head with Handbag. Others were stylized cartoon faces and configurations, reminiscent of Astro Boy and Speed Racer.

“ASS and I are making a showjoe mahngah.”

“Um... you ‘n’ who are making a what now?”

“Shōjo manga—that’s a girl-centered comic book. All the rage in Japan these days. Moto Hagio’s They Were Eleven—Riyoko Ikeda’s The Rose of Versailles—”

“But... you’re making it with...?”

“Working with—Skinner, of course. Ever heard of ‘sublimation’? When a guy (to give him the benefit of the doubt and call him one) channels frustrated urges into something worthwhile? Well, nobody’s more frustrated than ASS. He’s writing the story for my graphics. The more graphically I stymie him, the better he writes. It’s a win-win situation.”

“Well, but... for him too?”

“For him most. Otherwise he’d do nothing but flap his flippers.”

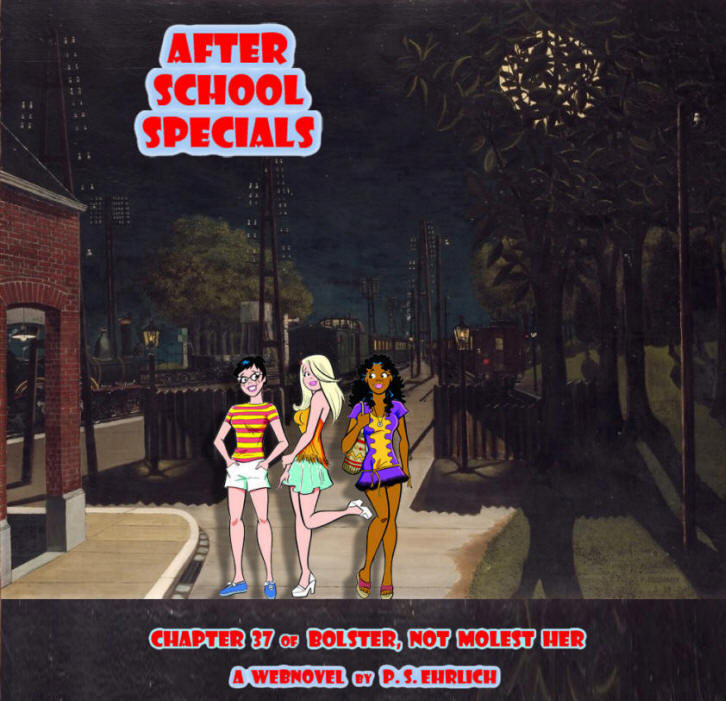

“Sounds like a bad After School Special,” tutted Vicki.

“Exactly—an ASS for an ASS. Oh, and when he said ‘Wouldn’t she be perfect’ this morning? He meant you, as a model for one of the characters.”

“Who—me? To, like, pose and stuff?”

“We’ll talk about it later,” Jenna stated, rummaging through the zippered portfolio for her Spanish text and notebook. “Right now let’s get started on this proyecto de identidad. I’ve got better things to do than it during the next two weeks. Soonest over, soonest clover.”

“Y’think Diana’d agree?” asked Vicki; and they shared a snortle at Diana Dabney’s struggle to express that she’d rather be boiled in oil than do a two-week project with Dennis Desmond—particularly one where’d they’d share their Personal Characteristics.

“Usa las palabras correctas, Señorita Dabney.”

“¿Hervir en Crisco, comprende? ¡Hervir—en—Crisco!”

*

On Tuesday morning Vicki dispensed with baggy T-shirts and donned her favorite purple top—the latest in a series, each of which Joss called “your sexy purple top”—as befitted a potential showjoe-mahngah model. Jenna’d declined to give any further info regarding this, except to assure her that she (Vicki) would pose for her (Jenna) while “that ASS” (Skinner) was nowhere within visible range.

The first three hours of Tuesday’s schoolday went by without undue worriment. Then Vicki descended to Room 221 for Geometry, and found a set of concentric circles forming just outside the open door. At the set’s innermost center a confrontation was taking place between two girls garbed in the exact same outfit: magenta satin blouse, Sasson designer jeans (the brand you had to wriggle into while lying down) and open-toe platform clogs. One of the girls was Gigi Pyle, the other Isabel Carstairs, and they even had identical skintones—scarlet vermilion, from hairline to collarbones—as they stood nose to nose with teeth bared, fists clenched, and bosoms heaving.

This was being appreciatively observed by an outer circle of boys, Mike and Brad and Floyd among them, who’d heard about Isabel being stripped half-naked Saturday night at the drive-in, and now reckoned magenta satin might get shredded off Is or Gigi or both—which would be a dandy way to study spherical constructions.

The set’s furthest perimeter was circled by girls like Robin (who grinned at the chance of seeing turmoil) and Britt (who sported her Red Queen cause-of-all-the-mischief demeanor) and Vicki herself (who simply wanted to remain uninvolved). When Mr. Rankin stepped out to ask why everyone was loitering in the hall, Vicki dashed past him into the classroom—

—but not before seeing Britt lean in to murmur something that absolutely poleaxed Isabel. Who then got elbowed aside by fit-to-be-tied Gigi, while Robin suggested they sign up for a bout of intramural mud-wrassling, as done by Betty the amnesiac in last month’s Archie at Riverdale High.

“Well now,” Mr. Rankin said, after Is got propelled to her desk by Brad and Mike. “If we’re finally all seated, let’s open our books to page 65... 65, is it?... yes, 65... and continue with Inductive and Deductive Reasoning—”

yyyyyyaaaaaahhhhhh

deeeeee-laaaaaayyyyyy

HHHEEEEE-HHHOOOOO

rose a wailing keening yodel-howl, with the resonant reverb of a banshee migrating from Ireland to the Alps.

Transfixed, the class stared as Isabel tipped her crimson countenance toward the ceiling and let loose an even spine-tinglier second outcry:

y-y-y-y-y-y-a-a-a-a-a-a-h-h-h-h-h-h

“Should we... maybe one of us should... will you please take her to the nurse’s office?” bleated Mr. Rankin—at Vicki, of all people.

Why? Because she was the girl sitting nearest to Isabel? Whose numerous male neighbors could not be trusted with such a task? Even if they were too flabbergasted by this paroxysm to take hornyboy advantage of it? Oh for Gahd’s SAKE...

Vicki unwillingly got to her feet. Turning to Robin (whose undyed chocolate brows were raised practically off her forehead) with a silent plea to take good notes for me. Bestowing a black laserblast on Gigi (who ignored it) and Britt (who basked in its lacerating beam). Gathering her books under one arm, Isabel’s under the other, leaving two fingers free for Mr. Rankin to insert a furtive hall pass between. (Eww.)

By this time Is had bolted through the doorway, legged it down the corridor, and vanished inside the second-floor washroom, from which a couple of tobacco-scented punkettes soon made an indignant slambang exit.

“Can’t do nothing in this craphole!” groused Razor Reid.

You can have the latest in a series of Pfiester Park flashbacks, Vicki thought as she pushed past la puerta into el baño and her memory of Stephanie Lipperman’s phlegmy sobs. Which had been minor tweets compared to the unearthly whoopage Isabel was doing here and now behind a closed stall hatch.

“Is? C’mon. I’m supposed to take you to the nurse—”

“Go ‘way!”

“Fine. I’ll leave your stuff here by the sinks—”

“No, wait!”

Out of the stall slithered a study in magenta: her face the same color as her blouse, except where liquidated eye makeup left inky downstrokes; her swollen lids were shut tight.

“Tell me the truth... is it as bad as I think?”

“Is what?”

“How I look!”

“Oh. Well, yeah, probably. C’mere—”

Tug of magenta sleeve over to sink; dampened paper towel placed in trembling hand.

“Those bitches,” went Isabel, blindly mopping the wretched refuse of her expensive cosmetics. “Those bitches.”

“Yeah, that’s Gigi ‘n’ Britt for you. Robin calls Britt the ‘Queen Bitch,’ so I guess that means Gigi’s the Empress.”

“This has been the worst week of my life, the very worst. I wish I was dead. I wish I was buried at sea.”

“Well, maybe the nurse can give you something for that. C’mon—”

“I can’t go out there, looking like this!”

Oh for Gahd’s SAKE. “Okay. Hold this book up close to your face. If anybody’s out there, maybe they’ll think you’re reading.”

“But then I won’t be able to see where I’m going.”

“I’ll guide you there, okay? Now hurry up, I need to get back to class!”

She escorted the invalid out of the washroom, around to the stairway and down it step by step, with open-toe platform clogs threatening to stumble over every one. Isabel kept her face crammed in the upside-down Essentials of Geometry, through which a muffled voice asked: “Vicki?... Can I talk to you?”

“Make it fast, we’re almost there.”

“Not now. After school.”

“I’m not on the team anymore, Is. I won’t be going to Multch North—”

“Well I won’t be either, not now! They excused Laurie just for catching a little cold—I’ve been sick since Saturday night, and was absent all day yesterday!”

(Vicki’d guessed she’d dosed herself again with warm saltwater to upchuck out of coming.)

“So can you meet me at the station after school? I’ve GOT to talk to somebody!”

“Talk to the nurse, that’s her job—”

“Not an old person! Please, Vicki? You’re the only one I can trust!”

Shades of Candy Gates (“Velma! You’re the only one I can depend on!”) whom Vicki’d avoided running into all year so far. Now here were Isabel’s bloodshot aquamarines peeping imploringly over the top of the textbook, ready to shed a fresh batch of tears.

What sin did you commit to deserve this? From somebody you had every reason to dislike; who’d attempted to steal Dennis Desmond from under your nose four scant days ago.

Okay: every reason but one. Undeniable and unrejectable as ever: Isabel was the spitting (or at least dripping) image of Patricia Elaine Volester—eye color excepted.

And just last night there’d been a bad dream about Tricia in trouble, Tricia in danger, Tricia in need of rescue and salvation. You could only guess how often Ozzie and Felicia’d had such nightmares. Not a word had anyone heard for two months now; no telling how many months might pass before any came. You could only hope Tricia could depend on the kindness of nonpredatory strangers, out there in Tinsel Town or wherever she might be.

(Sigh.) “Meet you where’d you say? The station? You mean the uptown El?”

“Yes—I know a place where we can talk, private-like. Pleeeease say you’ll come.”

(Again that melting marshmallow oozy-coo!) “Look, I’m not promising anything... and if I’m not there by, say, 3:45, that means I can’t make it. ‘Kay? Now get in there—”

Cutting short profuse gratitude by shoving Isabel and her possessions through the nurse’s office doorway.

Less than an hour later, Natalie Fish dropped by Room 325 to bawl “Hello, Mrs. Ivy!” in Grandma’s morbidly obese ear. “Okay if I have a word with Vicki Volester?”

“Of course, dear. Just keep your voices down,” Grandma said quite lucidly, before relapsing into her customary Study Hall mumble.

Sammi Tiggs offered Nat her desk, moving to the one in the back row left vacant by Bunty O’Toole since the First Day. Nat sat down more heavily than usual, looking less like a momma penguin than Abe Vigoda’s aged detective Fish: hangdog even though he’d gotten his own spinoff show.

“All righty,” she exhaled. “What’s the deal with Isabel?”

(Gotta give credit to the junior class grapevine—it’d taken Natalie fewer than sixty minutes to hear about this from Thirsty K, who’d heard about it from Nancy Buschmeyer, who was a Fourth Hour student assistant in the nurse’s office.)

Vicki filled Nat in on firsthand particulars, excluding any mention of maybe meeting Is at the El station after school.

“I might’ve known,” groaned Nat. “Here I was thinking we stood a good chance against Multch North.” Whose Lady Hurricanes led the JV Shoreside Division, but had been shaken up by a near-riot after their win at Multch East last Thursday: the first time any North team had played on an East court or field since their future consolidation got announced.

“How’s Doreen working out?” asked Vicki.

“Put it this way—at yesterday’s practice, she didn’t set any muffins on fire. I don’t suppose there’s any chance you might reconsider...?”

“Me? Oh—no—thanks for asking, but I wouldn’t play any better than I did last week. Anyway, I’ll be in the stands rooting for you Thursday, against... who’s next?”

“Triville—the Red Devils. Maybe we’ll have something to root for by then.” Shrewd Abe Vigoda glance: “If you run into Is anytime soon, tell her to get over whatever’s ailing her as soon as possible. We need somebody besides Alex who can dig-and-roll-and-live-to-tell-about-it.”

Vicki spent much of Lunch 5D trying to devise unhurtful excuses for blowing off any talking-to by Izzy-Whizzy, which was sure to be soppy-gloppy. She wanted to ask Jenna for advice, some clever contribution that wouldn’t leave a scar; but with Lisa sitting right there on the qui vive, it wasn’t safe to whisper or even risk slipping a note.

Joss had no such compunction in Sixth Hour English; yet they had barely enough time (or space, as Jerome Schei hovered nearby) for Vicki to super/sub-share the gist of the day’s goings-on, before Mrs. Mallouf barged in to quaff coffee and natter on about some old play called The Crucible. Fortunately Madeline Wrippley had a stack of Salem witchcraft handouts to distribute, and Joss adroitly slid an appendix into the one she passed to Vicki:

Just what Vicki needed. That and Jerome leeching onto her heels from the fourth floor down to the first (again losing Joss on the third) to the very door of the girls locker room, where she shook him loose without disclosing the latest latest. He’d receive it soon enough from Laurie—one would assume; though Laurie was still acting residually weird and not nearly as avid for gossip as she used to be. (Worry about that some other time.)

Sheila-Q wasn’t surprised that Britt’s dart-and-flicks could devastate the vulnerable, or that Gigi Pyle was capable of being eine Kaiserin der Hündinnen. (Why Gigi’d enrolled in German rather than a romance language was a mystery to Sheila and Robin, who relished her attempts to wrap a Dixiefied larynx around phrases like “Ich spreche nicht gut Deutsch.”)

“’Member how we used to say it’d be a lucky afternoon when Robbo’d laugh so hard that milk’d shoot through her nose? Well, now it’s double lucky if you see Gigi shpritz when she talks—triple lucky if she has to wipe her mouth afterward!”

Vicki wished nondisgusting luck to S-Q and Laurie against the Hurricanes; likewise to Coach Celeste, after providing her the same lowdown on Isabel’s ailment that had already been given to Natalie.

Lowdown was right. Isabel might wear French-cut butterflies beneath French-cut jeans, but Vicki’s butterflies were re-congregating in her stomach to disturb digestion of grilled cheese and vegetable soup. After the bell’s final P-E-E-E-E-A-L, they fluttersnuck her out across Hordt Field to the back gate on McKinley Avenue; then half a mile east to the uptown El station, whose platforms were occupied by a miscellany of mid-afternoon commuters...

...none of whom bore any resemblance to Isabel, Tricia, or Lucia Vantrop.

Vicki scanned the platforms again with one eye and scowled at her wristwatch with the other. Stood up! Now I’ll have to sprint back to catch the bus—

“You came,” said a remote voice from close at hand.

“Is...?”

“Yes, it’s me.”

You could’ve fooled Vicki. Instead of skintight designer threads selected for their allurability, Isabel had on a semi-shapeless sweatsuit of generic gray. Her goldilocks were tucked within an unadorned ballcap, and her aquamarines were concealed by a pair of dime store shades that Jenna Wiblitz wouldn’t have allowed on Millbank Street.

“So glad you came,” said this apparition. “Are you hungry? There’s a place up on Campus that bakes the yummiest pastries.”

Vicki’s butterflies let out a collective growl. Grilled cheese and veggie soup were all very well, but pastry rang a totally different bell; you could put up with a lot of gloppytalk in exchange for gloppytopped gateaux. (Last summer Mrs. Denvour had decided that she, Crystal, and Crystal’s little sister Amber were getting too plump, and so began freelancing “healthy cupcakes” that Vicki’d been too polite to complain about at their Labor Day weekend barbecue.)

Wait together for the northbound train, you on semi-tenterhooks. Suppose the Gondolier team bus made a 180-degree wrong turn en route to Multch North and discovered you here with Isabel, whose volleyball truancy would somehow be blamed on you? But maybe even Mauly wouldn’t recognize Is in her dowdy camouflage getup...

“There’s Floyd, dancing at us,” Is quietly observed.

Over on the opposite platform, “Hiawatha” was leering their way as he performed a Huggy Bear hustle that took him into a southbound train. Bound for Willowhelm, perhaps, to try his luck with unsuspecting Spaghetto girls. He got no responding do-si-do from Isabel, no flaunting of figure (difficult to do in a sweatsuit) or flirtytoss of hair (confined to ballcap). Nor was attention paid to other guys at the station or on the train they presently boarded, though some were cute and some were college-aged.

She really must be sick, thought Vicki; uneasy now about how responsible she (Vicki) would have to be for her (Isabel) if she (ditto) showed symptoms of getting worse.

For a minute they sat listening to the familiar lickety-click of public transit in motion. Then, just loudly enough to be heard, Is said: “When I was little, Mauly’d tell me the noise a train makes is really chains being dragged by the ghosts of everyone who’d ever ridden it—and are still riding it, there beside us. Not friendly ghosts like Casper, but zombie vampires that crawl inside your head through your mouth and nostrils and earholes, to suck your brains out while you sleep.”

“...well, y’know, big sisters...”

“Then she’d hide under my bed and make sucking sounds. Night after night. ‘Cause I’d scream every time.”

If you believed Jerome Schei’s scuttlebutt, the entire Carstairs/Altdorf/Mansfield clan was clean crazy. And had been for six generations, starting with the first Lafayette Carstairs (Mauly and Isabel’s father was the fifth) who claimed he’d saved Abraham Lincoln from being struck by a runaway horse-and-buggy outside the Putnam County Courthouse in 1845. Lafe parlayed that assertion into vigorous office-seeking during the Civil War (till Honest Abe said “I ought to appoint someone who can kick Carstairs downstairs”) while making a fortune, losing most of it, and depositing a dependent or two in lunatic asylums. This set a family pattern that persisted to the present day: Mauly saw a shrink twice a week, when she bothered to show up; Arabella Mansfield (Jive’s mother, Mauly and Isabel’s aunt) shuttled in and out of private rehab centers; while one of the Altdorfs down in New Braunfels had been put away for introducing his girlfriend’s husband to a sausage-making machine.

So if Is was “ill,” how liable might she be to go completely bonkers as the train pulled into the Hereafter Park station and she said “Here we are,” softly (if not sinisterly)?

“Campus,” to northeast suburbanites, meant Lakeside Central University. Vicki’d been brought here fairly often by alumna Felicia and sports fan Ozzie, to attend artistic events and Yellow Jacket games; but she didn’t know her way around the place, and had no clue where Isabel was leading them through a constellation of ivy-covered edifices. It was after four o’clock now and Campus was sparsely populated, so any cries for help would probably go unheeded at the far end of this ivy-covered alley—

—where a shabby sign over a dingy window read La Boulangerie de la Ruelle. Whose proprietor was a lantern-jawed Parisian apache who glowered at them over a flour-speckled counter, around which wafted all the fragrances of fresh-baked heaven.

“Deux tartes aux myrtilles étoillés, s’il vois plait,” Is told the apache.

“Bien,” he grunted with grudging respect; and an instant later the girls were seated in a dark booth staring down at circular starry night skies.

“What...?” asked Vicki.

“Blueberry pies,” answered Isabel. “The stars are made of crème Chantilly.”

Vicki was hesitant to taste hers, having been unable to enjoy that particular fruit since reading how Avery’s frog splashed soapy water over a blueberry pie in Charlotte’s Web. Yet it took only the teensiest morsel to banish that memory; and she dialed down conversation to “Mmm’s” at the pie and “Mmm-hmm’s” at Isabel.

Is picked at her own plate while burbling about various dilemmas and distresses. Vicki tried to pay occasional attention, vaguely associating mention of “Mauly’s coke spoon” with the bottle of Coke syrup that used to be the only good thing about childhood vomiting. Each barf earned you a spoonful of delicious relief, till Goofus got greedy and made the folks resort to treating nausea with plain old Pepto-Bismol.

“Well,” Isabel sighed after awhile, “thanks for listening. I hope we can be friends now. I wanted to before, but every time you looked at me you acted like I was covered in spiders or snakes.” Said with a dollop of reproach that sent guiltpangs through Vicki’s heart, even as she sent the last blueberry swallow down to satiate her tummy-butterflies.

“I’m sorry about that. It’s just—you kind of look a whole lot like my big sister, who sort of ran off to California a couple months ago. We’re not sure where she is.”

“Ohhhh,” breathed Isabel, “you are so lucky. I’d give anything to say that. But do you really have a sister who looks like me?”

“Yes—she takes after my dad’s side of the family, I take after my mom’s. And you look like her. ‘Cept she’s got emerald-green eyes.”

“She must be very beautiful.”

(Snortle.) “Yeah. She is. Well... you both are.”

“Well, so are you—‘specially when your tongue matches your top.”

“Oh Gahd! Does it?” went Vicki, sticking out her tongue and staring at its deep purple tip. “Hah bong wiwwih thay thih way??”

At which Isabel let out a peal of crème-Chantilly’d laughter.

*

“...so she lent me the dough (ha-ha) to buy three more pies to bring home, and two of them are gone already,” Vicki told Joss during their nightly phone chat. “Dad and Goof practically inhaled ‘em—even Mom had two slices, and you know how (she says) she’s ‘watching her weight.’ I’ll try to bring you a slice tomorrow—meet me at the west trophy case before First Hour. Even if it gets all shmushed on the bus, it still ought to taste how-do-you-say magnifique.”

“You do know what that means, right? Not magnifique—‘tarte aux myrtilles.’”

“Like I said—blueberry pie.”

“Nope! It means whortleberry tart. You ate a whortleberry tart with Isabel Carstairs! No wonder your tongue got stained—”

“Now cut that out, she was really nice, like a whole different person. I kind of hinted she could make a lot more friends (girls, at least) if she did that more often ‘stead of using her bod to, like, beguile every guy she meets. But y’know what Is said? ‘Boys have to like me.’ It was so sad.”

“Not as sad as Meg saying ‘Why don’t boys like me?’”

“Oh shut up. Your sister had more boyfriends than either of us have managed to have so far.”

“You shut up. WE are selective and won’t settle for just anybody’s body. Oh, speaking of which—did you warn Isabel that Spacyjane’s ticked off at her for besmirching Floramour’s reputation when the Blue Fairy turns her into a real girl?”

“Besmirching?”

“Hey, you said ‘beguiled.’”

“No, we only discussed how much Is looks like Tricia, not Spacyjane’s doll. You’re all in the same French class—you can talk to both of them about it then. Just be sure your tongue is purple when you do.”

*

Further dramatic heights were scaled on Wednesday. Vicki successfully conveyed the Tupperware’d pie slice to school intact; but at the trophy case Joss pretended to drop it, Vicki dove for the save, the girls conked their noggins, and the slice got shmushed after all.

“You didn’t even get a chance to see the star!” mourned Vicki.

“Oh didn’t I?” moaned Joss, rubbing her curly head.

Then Vicki found Skinner blocking the aisle again in Room 312 as he rambled discursively about the manga’s storyline to Jenna, who was briskly sketching his pigeonface as a cracked-open piñata.

“Vicki, would you be so good as to kick this ASS out of here?” she requested.

“Shoo!” went Vicki, as she did to Alex’s chihuahua Tonio when he got too frisky with her footwear. (Yermak the Borzoi was too dignified to do more than give shoes an inquisitive sniff.)

Skinner gave Jenna a long last look of raw dotage and an offhand glance at Vicki before lumbering turtlishly away, saying “I still think she’d be perfect...”

“Well, you did that perfectly,” chirped Jenna. “I’ve been trying to make him go shoo for the past seven years.”

“Got any aspirin?” Vicki asked. “This day’s shaping up to be a headache...”

Substantiated outside the Biology lab before Second Hour, when two contretemps took place simultaneously. One pitted Nanette Magnus against Petula (alias Downtown alias Tayser) Pierro: they hadn’t been simpatico on last year’s Cicada staff, and a month of lab partnership had excavated deeper antagonisms. Each regarded the other as a bony-butted skank, which wasn’t fair to Nanette’s caboose since it’d filled out during a summer with Boffer Freuen, whereas Tayser’s had shrunk since hooking up (or as she would phrase it, hawking up) with Epic Khack.

The second contretemps was going on (and on, and on) between Tess Disseldorf and Fast Eddie Wainwright. Those two had reconciled three times in the past four weeks but now were breaking up again, even more vociferously than their typical wont.

Tess, unlike such lookit-me! lasses as Carly and Isabel, dressed with demure modesty even on Maine Street Beach. This however was a façade, to which Tess coupled a stance and gaze of insolence so spellbinding it could seduce the trousers off a bronze statue. Milder-mannered girls might pine for guys to ask them out; Tess Disseldorf went on safari and bagged big game with infallible aim, mounting head after head over her metaphoric fireplace. Fast Eddie resented this, both for his own head’s sake and because he thought Tess should keep her succulence under wraps exclusively for him.

“When ya go with Fast Eddie, ya gotta go with Fast Eddie!”

“Quick Eddie,” heckled Tess. “Hasty Eddie—Premature Eddie—”

At which combustible point Vicki broke into the breakup with a Wainwrightish “Come ahn, come ahn,” trying to herd all the adversaries into the lab. (Mr. Dimancheff was known to lock out late arrivals and dock them a day’s attendance.) Delia Shanafelt pulled Nanette away from Petula (“Be careful, she carries a knife!”—“You’re thinking of Razor! I’m Tayser!”) while Crystal Denvour reined in Tess, giving her incidental kudos on behalf of the FEEE (Fast Eddie’s Exes Everywhere).

“Careless Eddie—Messy Eddie—Slapdash Eddie—” Tess continued to taunt.

“Do not become overwrought,” Mr. Dimancheff notified her, closing the door and shooting its bolt. “We are not here to become overwrought. Today we are here to study membranes. As Maeterlinck tells us:

|

Most

creatures have a vague belief that a very precarious hazard, |

“By the time we complete this unit, your belief about membranes will be neither vague nor precarious. Let us be transparent about that at the outset.”

No one chose to refute Mr. D by so much as a cleared throat. Vicki did move her head far enough to exchange an eyeroll with Nonique—and was alarmed to see twin fires blazing in her usually reticent sockets.

Oh no! What now?

“—the membrane regulates whatever enters a cell, such as food; and whatever exits a cell, such as waste—”

(Eww.)

Do not get distracted—you are not here to be distracted. Science is your weakest subject, so you need to pay strict attention to this membrane lecture.

Just as you need Nonique to save both your non-bony butts in this Biology class.

Whisper on your way out of Lab: “(You okay?)”

Sidelong twitch: “(Can’t stand the name Eddie!)”

And with that Nonique strode off to Instrumental Music, leaving Vicki to brood through World History while Ms. Goldberg talked about Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path—presumably to Sixteen Candles and a driver’s license. The whole Buddhist shebang, including those yoga poses Coach Celeste had you do, was intended to attain a “cessation of suffering”—which apparently was still out of reach for Vernonique Smith.

Though not Isabel Carstairs, who popped into Geometry on the brawny arm of quarterback Jeff Friardale, who gave her a this-is-my-good-profile smoocheroo right in front of Gigi Pyle, who’d been plotting to ensnare Jeff for her own exploits but now had to flinch from one of Britt’s derisive dart-and-flicks.

(As Isabel, licking her lips, tipped Vicki a gleeful little wink.)

Then came Homeroom/Study Hall, where Nonique sat with extinguished eyes till Vicki couldn’t bear it any longer and passed her a note:

Nonique sustained her downcast posture for a yoga count of one, two, three, four, five... then picked up a pen:

This last note-passage made with a reviving twitch of mouth-corners. Which stayed upward when Sammi Tiggs whipped around to gasp “Ohmygosh! Don’t I have a book report due today? Laurie’s supposed to remind me of stuff like that! I can’t even remember which book I didn’t read!”

Vicki calmed her down and had Sammi check her carryall, from which she drew a dog-eared Harlequin paperback titled Bride of Zarco.

“Sounds like a horror story,” murmured Nonique.

“Oh no, it’s a thriller—and the heroine’s named Samantha!”

Better to turn in any book report than none, they reasoned; so in the cafeteria Sammi left her lunch uneaten while churning out a last-ditch essay on this epic tale, much to Lisa Lohe’s disapproval:

“No English teacher will accept a report on that sort of book!”

“Miss DuJardin will,” predicted Jenna. “Miss DuJardin appreciates fine trash.”

“It is not trash!” protested Sammi, focused so resolutely on scoring 500 words that she missed Tab Tchorz meandering past.

“Fine trash,” said kindly Link Linfold, who harbored a crush on Samantha that everyone else at the cafeteria table suspected (and Lisa resented).

“Great trash! Can I borrow this?” asked Holly Brollis, nearly choking with delight as she skimmed through Bride of Zarco. “I love it—there’s even a stomach-pumping scene!”

Nod from Sammi as the bell rang and she galloped off, report in hand, watched wistfully by Link.

Vicki climbed back to the fourth floor for more of Mrs. Mallouf’s Crucible boilover, plus convincing Joss that an overture into Nonique’s personal space needed to be a solo venture, no matter how badly Joss might want to go too.

“Breaking the ice has to be done super extra carefully,” Vicki told her, “or else we’ll fall through and get frozen out.”

“What is this? Are you writing torch songs for fortune cookies now?”

“Oh shut up.”

“You shut up. And memorize every last detail of what her bedroom’s like!”

Felicia, when phoned, was equally eager and agog (as Nonique expected). During Fel’s first conversation with Mrs. Smith two weeks ago, she’d invited Nonique’s family to dine at Burrow Lane—and then been puzzled by the convalescent Vicki’s aghast reaction:

“Budder! I ab dot lettig deh Weeboudder see be lookig like dis!”

“Now darling, wasn’t he injured all those times playing basketball? I’m sure he’s used to the sight of swollen noses and so on.”

But Vicki’d vowed to go on a hunger strike, so Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was postponed—indefinitely, as it turned out, since the Rebounder got called out of town for a Universal Nutrition publicity tour.

Nor was that the only ad campaign afoot. Ms. Schwall coaxed Vicki into coming in early the next morning to stand under the front portico and help Alex, Michelle, and Ann Hew hand out fliers to promote the home volleyball matches against Triville. Both the varsity and JV had upset Multch North yesterday, and there were hopes for momentum going into the weekend tournament at Startop; so there really ought to be a few fans in the stands. Vicki winced at the idea of offering leaflets to strangers, some of whom were bound to ask if that had been her sweet ass in that Channel photo. Why couldn’t the fliers be shoved anonymously through locker vents, like for the Vinyl Spinnaker concert last February? Yet it was still better than going oncourt and making a fool of herself in compression shorts.

After Phys Ed she lingered in the gym long enough to coordinate Thursday’s early arrival with Alex and wish her a good practice. Then it was off to the bus stop with Nonique, neither of them saying much as they rode the Big Green Limousine westward to Panama, through the Tunnel of Sighs, over to Lesser and past the Foxtail stop to disembark at Sprangletop. Walk two blocks over to Kessell Road and then down to Jimson Drive, Vicki remembering how Robin had feigned a heart attack at the news that a black family had moved within hollering distance (if you could holler a mile) of Villa Neapolitan.

“‘Ohhh, this is the Big One! Y’hear that, ‘Lizabeth? I’m comin’ to join ya—’”

Vicki’d read Robin the riot act: “This is a very nice girl who’s having a very hard time, and you are not gonna make it any harder for her!”

“Okay, okay! Jesus, Loopy, lighten up! I wasn’t planning to go burn a cross on her lawn or anything.”

“Well, see that you don’t.”

(Pause. Then:) “The Rebounder’s what—six-foot-eight? He must drive a grape-soda-colored stretch Cadillac—”

“Robin...”

As a matter of fact, Vicki couldn’t say for sure how hard a time Nonique might (or might not) be having. Some days she seemed mellow-‘n’-laidback; others were a repeat of the First Day’s rifeness-with-pain. Never did she kid around like Rhonda Wright, who liked to embrace the nonplused Meredith Wainwright as her separated-at-birth soul sister—“’cept I got enough sense to come in outta the wain!”

But sometimes (again as on the First Day) Nonique came to an isolated standstill, and so suddenly you almost fetched up against her.

As you did now.

“Well,” she went, “this is it.”

On the corner of Jimson and Kessell: behold the Old Brandoffer Place.

That was a name of clout and substance in Vanderlund. A Brandoffer had been among the pioneer missionaries who stood with Jan van der Lund in founding the College of the Hereafter. His descendants included a director of The City’s Board of Trade, a member of The County’s Board of Commissioners, and an eminent jurist who’d refused appointment to The State’s Supreme Court because he disliked traveling “over those God-damned prairies!”

This plainspoken magistrate married a sibilant heiress, daughter of Silas Kessell the copper cookware king, who’d purchased substantial acreage of what was then farmland from father-in-law Jesse Lesser. Silas and his son Ezra had spacious ambitions to cultivate this agrarian tract into an independent suburb called Lesser Park, with a north-south thoroughfare named after themselves. Here the newly-robed Judge Brandoffer built a half-timbered Tudor Revival house in 1907; and here he treated his only child as someone who had “a brain in her head—not a wad of wet sawdust.”

Her mother wanted Emily Brandoffer to be “finished” at Miss Startop’s Select School for Young Ladies; the judge sent her to VTHS, where she was salutatorian of the Class of ’13 and presided over the banquet where Whielding Wheaf made his “veritable citadel of knowledge” speech. Her mother wanted Emily to marry a nice acceptable man and raise a respectable family; the judge sent her to law school, after which she joined her father’s firm at a time when female attorneys were classified with bearded women on the freakshow circuit.

Over the next three decades Miss Emily built up a practice specializing at first in probate law, then branching out into real estate and property. This diversification came too late to save her Uncle Ezra from ruin during the Depression, or prevent Lesser Park’s annexation by “greater” Vanderlund; but by the Fifties Miss Emily had become an unlanceable boil on the neck of Lyman T. Green and other developers partial to sub rosa dealmaking. Very often she would get wind of some stratagem before the deed could be inked, and either scotch it outright or skew it in somebody else’s favor.

In her youth Miss Emily had been acquainted with Jane Addams, Mary McDowell and Sophonisba Breckinridge, but felt no yen to follow them into social service—at least not directly. She too could operate sub rosa, prompting and steering from behind the scenes, and letting others take the fall (if needs be) while she drove selected measures toward the greater good.

On the Vanderlund Township School Board she was not a front-and-center advocate of district integration, and made no stirring speeches in the Pitched Debate of ’63. Yet her “Bunk!” reply to Eberhard Drexler’s garrulous Commieplot diatribe put an effective cork in the opposition. Miss Emily then played a noteworthy (though largely unnoted) role in the concoction of Happel Land as Vanderlund’s path to compliance with the Fair Housing Act, partly through what she called (though not for public record) “blackmailing bigots.”

Know the net worth of every citizen and the location of every skeleton, closeted or otherwise...

When she grew too frail of body (though by no means of mind) to continue residing at the Old Brandoffer Place, Miss Emily deposited herself in the same posh nursing home where Joss’s Grandpa Mac and Grandma Sadie had been sent. It put no crimp in how she managed her affairs or fostered the greater good; indeed, she decreed that her house should be rented to a family of color, the first to dwell in that inland neighborhood. (If you didn’t count domestic servants; and when Miss Emily was young, there’d been a local resolution to not employ Negro maids, cooks, chauffeurs, etc. if you were unable to quarter them on your premises, since Lesser Park certainly didn’t want them living there on their own.)

“We shan’t upset the apple cart—simply introduce a few pomegranates,” Miss Emily told her staff, instructing them to solicit an authentic black celebrity or semicelebrity who was married with school-age children, to whom assurances of minimal harassment could be made. And not idly, since she owned most of the mortgages on Kessell Road and Jimson Drive; and not even Lyman T. Green would dare engage in blockbusting on Miss Emily’s home turf.

Hence: “This is it” for Vernonique Smith, daughter of the Rebounder.

Who glanced warily up Jimson, down Kessell, then at the Old Brandoffer Place itself. From outside it gave the impression of a gingerbread house, and (as if to ward off hungry children) it was surrounded by a high brick wall with an iron-barred gate that Nonique unlocked and relocked once she and Vicki passed through. Same ritual at the arched front door, set between diamond-paned windows below an overhanging canopy. Yet even with a couple of barriers secured behind her, Nonique didn’t seem to breathe more easily; and Vicki too began inhaling/exhaling with heightened awareness.

This Place was not the Queen Anne mansion on Jupiter Street that she’d fallen in love with at first sight and happily sleptover at on Saturday nights. This was more of a cloister, silent and secluded, where visitors got the distinct sensation of being watched—not by some hostile neighbor peeking through drawn blinds, but by the Place itself: cagey and covert, full of disorienting vibes.

“(Want a pop?)” Nonique asked in an undertone.

“(Sure,)” said Vicki, wondering despite herself Will it be grape-soda-colored? till she was handed a bottle of Fanta Orange.

The girls had the Place to themselves, what with the Rebounder on the road and Mrs. Smith having a substitute-teaching gig, and Randle (like Goofus and Breezy and Patches Rumpelmagen) out raising sixth-grade hell till dinnertime. Nonique gave Vicki a quick tour of the first floor, where the Smith furniture looked like it’d been misdelivered to the set of a Bette Davis suspense movie—The Nanny or Hush Hush, Sweet Charlotte. Portraits of Nonique and Randle at various ages hung bravely on the looming walls, along with memorabilia from the Rebounder’s career—including a trophy, more plastic than metal, for winning the first championship of the late lamented ABA. It wasn’t very big so far as trophies went, but the chairs and sofa and so forth were all oversized as if to accommodate a professional basketballer’s frame.

Vicki nearly spilled her Fanta on the oversized sofa when a crack disrupted the stillness, causing Nonique to cringe and mouth Oh sweet mother. They stood motionless, awaiting further commotion—maybe from some racist zealot pounding a we don’t want your kind around here!!!!! sign into the lawn, like Judy Blume wrote about in Iggie’s House. But the Place resumed its watchful silence, and the girls restarted their hearts and lungs.

“(Old houses, y’know, make noises when they settle,)” Vicki suggested.

“(How ‘bout when they unsettle?)” replied Nonique.

She led the way up a wide Tudor staircase (that Anne Boleyn might’ve ascended) and down a dimly-lit Tudor corridor (that Bette Davis might’ve stalked or been stalked in) till Nonique twisted a knob and opened a door and ushered Vicki into a Tudor bedchamber (that might’ve been Princess Elizabeth’s prison cell in the Tower of London). It was largely vacant except for stacks of cartons, each marked “N,” and a row of unlatched suitcases full of folded garments. The closet was even emptier than Jenna Wiblitz’s; the furnishings were bare-topped and bare-shelved; and only a neatly-made bed (which Gran Schmelz would’ve approved of) showed any indication of recent use.

“You’re all packed!” cried Vicki. “You’re not moving away, are you?”

“Um, no... just haven’t got around to unpacking, yet...”

After a month or more here? Vicki, on vacation trips, couldn’t get through a single night without transferring the entire contents of her luggage to motel fixtures. “’Scuse me asking—but doesn’t your mom mind?”

“Oh, she minds, all right...”

Again a watchful silence filled the room.

Both girls happened to be dressed today in bright blue tops and plain blue jeans (not Sasson) whose snug denim seats hugged their round rear ends as they sat on the floor with yogafied grace (Coach Celeste would be proud) and leaned back against the bedside, taking sips of orange pop.

“Mind some music?”

“No, I love it.”

A cassette recorder was extracted from under the bed and switched on to play not rock or soul or gospel, but an album of oboe concerti.

Bracing herself with Vaughan Williams in A minor and a deeper sip of Fanta, Nonique cleared her throat. “So... okay... here’s the story...”

Of a lovely lady! sang Joss’s voice in Vicki’s head, necessitating the repression of a wild giggle and automatic Shut up! Nonique was tensely taut, on guard against any hint of being pitied or patronized, and an interruption now would doubtless seal her lips forever so far as Vicki was concerned. And Vicki was concerned, far more than she’d been about Isabel; thankful not to be distracted by blueberry pie from listening with both ears.

Nonique had no gift for straightforward narrative. She started in the middle, worked her way outward in several overlapping directions, jumped forward and sideways and off on tangents. Vicki would have to piece it all together with earlier and later disclosures, to form a coherent consecutive chronicle of Vernonique Smith: hearing echoes throughout of her own story and those of her other friends, as the solemn oboe music rose and fell.

Once upon a time...

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Return to Chapter 36 Proceed to Chapter 38