Chapter 22

Groundbreaker

“I said I’ll come cheer you, and I will,” Joss reiterated later that week. “But you know how I feel about me running. And you also know I’ve got my cornet lesson then. So good luck, Gahdspeed, and don’t break a leg!”

“Wise guy,” said Vicki.

“Call me when it’s over. Like, if you need another bike ride home—”

“Oh go blow your horn already. I hope you have to hit high C.”

“Hey—you’re gonna wow ‘em.”

“Well... hope so, anyway.”

“Know so. Every way.”

“Yeah, well, thanks... Are you sure you won’t come with me?”

“La la la la, I can’t hear you, I can’t hear you—”

“(Jo! Will you ever let anybody else use the damn phone??)”

“Ooh, Meggy’s getting crabby—and grabby!—gotta go—call me!” (Click.)

So Vicki had to jog down to school by herself on Saturday morning. She’d known perfectly well Joss wouldn’t react favorably to Friday’s homeroom proclamation that, contrary to rumor, VW was going to start a girls cross country team this year, and everyone interested should sign up at noon on Saturday.

Mrs. Driscoll’s P.A. communiqués weren’t open to doubt; yet Vicki still turned to Fiona and asked, “Did she say cross country?”

“(Noooo—Crawdaddy,)” muttered Fiona, rustling the pages of that magazine.

Noooo chance Fiona would try out. Vicki’d never actually seen her with cigarettes, but she certainly looked and sounded like a precocious smoker—one who’d cough like Mr. Folz if she survived as long as he had. Nor was there any point inviting Robin Neapolitan to try out: Robin objected (forcefully) to any sport not involving internal combustion engines, with a high crash-and-burn likelihood.

Which Vicki’s cross country career might very likely have.

What were the odds of her making the squad? Or even being seriously considered? She could envision a hundred Olympic-level sprinters looming ahead of her, vying for the honor of membership on a groundbreaking sports team.

It was to have been launched that summer by the ninth-grade Phys Ed teacher, Miss Gibb, who liked to remind people she had the same name as the first woman to run the Boston Marathon. Miss Gibb had chosen a team captain, freshman-to-be Frieda Pieper, who was obscurely related to the longtime announcer at the Friendly Confines. (At any rate she’d been excused from classes a year ago to go attend his funeral.)

In June, Miss Gibb had worked closely with Frieda’s family to organize the new team—so closely, in fact, that Frieda’s mother had sued Frieda’s father for divorce in July, citing Miss Gibb as co-respondent. Mrs. Pieper’d also yanked Frieda out of VW and away from Vanderlund, while Miss Gibb submitted her resignation to Mrs. Driscoll (and now, some whispered, was carrying Frieda’s half-sibling-to-be).

Net result—no girls cross country squad.

Or so rumor had it, till yesterday’s proclamation.

Vicki neared the now-familiar corner of Knopper and Oakapple, summoning all her courage as she anticipated a throng. But the only person on the corner was Alex the Gazelle, who started waving vigorously the moment she noticed Vicki’s approach.

Me? Vicki mouthed, pointing to herself, then slowing to a halt as shouts of laughter seemed to greet her.

“Cross country??” Alex hollered across the street and over the shouts.

Vicki nodded a tentative yes and jogged up to the school gate.

“Yay!” went Alex. “Mumbles, we’ve got seven!”

“S’nice,” said a soft little drawl, belonging to an older girl with a sweet round babyface like a happy Buddha. She gave Vicki a quick smile, then resumed flirtation with a tall guy in a Tequila Sunrise T-shirt. Despite his height he too had a babyface, one that didn’t appear to have yet felt the scrape of a razor, and “Mumbles” was reaching up to fondle his smooth babycheek.

Four other girls in running garb were hanging around inside the fence. One, deeply tan and robust, stood with stoic folded arms like Sacajawea waiting for Lewis & Clark to make up their minds. She was being chatted to by a long-legged black girl in a beep-beep! Roadrunner tanktop. (Vicki wondered if she might have a brother for Joss.) They, like Mumbles, looked like freshmen; as did a narrow-visaged ascetic type who stood apart from them, frowning intently at a clipboard.

The fourth girl, younger than the other three, was a brass-bold ringer for Mary Ellen on The Waltons: ready to wham John-Boy, Jim-Bob, or any other guy reckless enough to get in her way. Probably including the serpentine individual she was busy flirting with, who badly needed a soap and shampoo for the oily-natured. (Eww.)

Had those laugh-shouts come from Snake Oiler? Or Mary Ellen? Or both?

“NO WAY!” Mumbles abruptly erupted, giving Tequila Sunrise a playful shove. “Nelson, you are so FULL of it! HA!! HA!! HA!!”

As echoes bounced off the school wall, Alex asked Vicki a question.

“Sorry, what??”

“Which team are you on?” repeated Alex. Still on vigilant sentinel duty, yet somehow giving Vicki her full attention.

“Me? Um, well, I’m trying out for this one...”

“No, I mean are you on 8-Z? I thought so! You’ve got second period English with Miss McInerney, right? And Gym before that? I knew I’d seen you before. I’m Alex Dmitria—sorry I haven’t introduced myself till now—I try to get to know everyone in all my classes, but time goes by so fast, y’know?”

Vicki felt proud to be recognized by such a luminary. Alex had to be the most radiant person she’d ever met in real life: tall, slim, glowing with vibrant health. Her hair and eyes were as dark as Vicki’s, but Alex had a short pixie cut instead of a waist-long braid, and enormous supernovas instead of almond-shaped stars. Along with this incandescence came a worrisome glimmer that Alex Dmitria’s mainspring might be wound a trifle too tight:

“I am so glad you’re signing up, we really need seven to compete properly, I mean we could run as a team with just five but you need seven to displace, and anyway if you’ve only got five runners and one gets sick or hurt, y’know, you can’t run as a team. I mean there must be nine hundred girls in this school! If just three percent would show, we’d have another twenty here and not a thing to worry about. But where are they? Doesn’t anybody listen to the morning announcements? Ohmygosh what time is it?—it can’t be noon already, we can’t have only seven—Mumbles, how much longer can we wait??”

“Calm dowwwwn,” Mumbles drawl-advised. “S’not time to freak yet.”

“I am calm,” Alex maintained, pacing back and forth, making a steady-handed Girl Scout sign to prove her composure. “See that? Calm as a rock. So Vicki, did you transfer to Z? Which team were you on last year?”

“Me? Not any—I just moved here this summer. To Burrow Lane, off Foxtail Road.”

Alex’s face lit up even further, if that were possible. “You’re kidding! I live on Sprangletop, just a few blocks from Foxtail. That is so cool! Hardly anyone else lives so close. We could go running together—do you run to school in the morning?”

“Um no, haven’t had to yet—”

“Oh but you oughta! And before school’s a good time for me, if it’s not inconvenient for you. I could stop by your house Monday and—hey! Cross country??”

Vicki waved with Alex (if not quite as vigorously) as a Vega Notchback pulled up to let out two girls. The first one resembled a bunny rabbit—nervous expression, quivering nostrils, hair plaited in two thick pooftails—with a pooftail-tip caught between her teeth, being nibbled like a carrot. (Reminding Vicki of Eileen Agnew’s fingernail.)

Her friend seemed barely old enough to be in junior high: no sign yet that her chest or hips had heard about puberty. However, she possessed an air of blithe self-confidence that Flopsy Mopsy decidedly lacked; plus a sense of affectionate discretion, with which she tugged the pooftail-tip out of Flopsy’s mouth and tucked it back behind Flopsy’s ear.

Hi’s were exchanged, then more waving done at a Dodge Monaco bearing two more youngsters. This pair detested each other so palpably you had to boggle at their traveling in the same car—from which they exited out opposite doors, one coming around the front of the Monaco, the other heading nose-in-air around the back.

The frontcomer was a woolly baa-lamb, with a sheepish face and docile gaze (when not glaring sidelong at her companion); she chomped ruminatively on a fat wad of Dubble Bubble. You’d have to call the backheader a pretty girl (and envy her layered-look ‘do) though she did nothing but glare: sidelong, straight ahead, over the fence, down at her feet. As though she’d been forced to breakfast that morning on pickled eggs and sour grapes, and being here now was the very last straw.

More hi’s, then a great big wave at a Coupe de Ville cruising up for all to admire.

“Oh Lord,” snortled Mary Ellen Walton, “it’s Britt! I mighta known she’d make a hooptedoodle entrance.”

“Check out the guy driving,” said her oily boyfriend. “Zat who I think it is?”

“You know it—‘Hoyt Groningen, Action Weather!’”

It really was The City’s favorite TV meteorologist behind the Caddy’s wheel, returning their wave with a sorry-no-autographs grin. The girl sitting shotgun waited for this celebrity-furor to ebb, then hooptedoodled out of the car and through the gate. She was slightly built, sleepy-eyed, and had dark red hair—all like the Squeaky person who’d aimed a loaded pistol at President Ford just yesterday. But her shirt, her shorts, her gym shoes all seemed to breathe “Diane von Fürstenberg.”

“Sheesh!” went the Roadrunner. “Killer threads! She gonna run in those?”

“Sorry if I’m late,” said Britt, with a now-that-I’M-here-we-can-get-started smile.

PHWEET went a whistle, and they were confronted by a thirtyish man in light sweats. He wasn’t much bigger than Britt Groningen and had already gone half-bald, but was empowered (like Mr. Brown back in sixth grade) by an encyclopedic mastermind—on the subject of long-distance running, at least.

This was Mr. Heathcote, dubbed “The Minute-and-a-Half Man” after an ancient cartoon. He’d attended Elmhurst’s York High and run for their legendary coach Joe Newton. True, Mr. Heathcote had graduated before York won the first of their many cross country championships; but still.

“Gentlemen,” he told Snake Oiler and Babyface Nelson in a reedy yet steely voice, “unless you plan to sign up for the girls team, go elsewhere. We will delay proceeding till you are out of sight. Starting... now!” He clicked a stopwatch and stood waiting while the boys sauntered off—picking up speed when Mr. Heathcote observed, “I trust you ladies can move faster than those two.”

(Superior snortles from the dozen girls.)

(Silenced when their coach turned and faced them.)

“If you’re here expecting tryouts, you are mistaken. By being here today, you have made the team. Whether you remain on it is another matter.

“I won’t lie to you, ladies: we’re starting from scratch, and we’re starting late. We’ll be building our team from the ground up, more for future seasons than this year’s. You ninth-graders, who won’t be back next fall, will contribute more than your fair share.

“Nevertheless, I expect that when you look back on your time at VW, one of your finest memories will be of having been a member of this school’s first girls cross country squad!”

(Ragged cheer, led with vigor by Alex Dmitria.)

From the ground up entailed a whole new set of ground rules. To stay on the team, you had to attend practice four days a week after school and at noon on Saturdays. One unexcused absence meant missing the next meet; two meant you were off the squad. Tardiness counted as absence; so did detention. Smoking, drinking, drug use, academic ineligibility all meant instant dismissal. Good sportsmanship was a requisite, with teammates and opponents alike; you were to behave as a responsible representative of your team, your school, and your community.

“The most essential rule is dedication to running. In every kind of weather, over every kind of terrain. You must commit yourself to doing everything you can with everything you’ve got. If that means coming in dead last in a field of a hundred runners whose Personal Best is faster than yours, so be it—as long as you finish every race without quitting, constantly test your limits, and always strive to improve your own Personal Best. Do that, and we’ll be as proud to have you on our squad as you’ll be of yourself.

“Now’s the time to sign up if you’re ready and willing. Freshmen first, then you eighth-graders, then you in seventh. Give us your names and academic teams as I assign your numbers—”

#1: Lisa Lohe, 9-X (the ascetic clipboard-holder)

#2: Rhonda Wright, 9-X (the Roadrunner)

#3: Yvette Metcalf, 9-Z (Mumbles)

#4: Susan Baxter, 9-Y (Sacajawea)

#5: Alex Dmitria, 8-Z (ever the Gazelle)

#6: Sheila Quirk, 8-X (Mary Ellen Walton)

#7: Vicki Volester, 8-Z (hopefully as lucky a number as legend would have it)

#8: Britt Groningen, 8-X (Squeaky von Fürstenberg)

#9: Laurie Harrison, 8-Y (Flopsy Mopsy)

#10: Susie Zane, 7-Y (the blithe prepubescent)

#11: Karen Lee Bobko, 7-Z (the woolly baa-lamb)

#12: Caroline Appercy, 7-Z (sour-grapier than ever at bringing up the rear)

Mr. Heathcote led them through a warmup of stretches and calisthenics before staging the team’s first time trial. Six laps around the track: a mile-and-a-half, 2640 yards, or 2400 meters for the metric-conscious.

The twelve runners happened to finish in the same order they’d signed up. Vicki, who’d never run to a stopwatch before, was glad she hadn’t disgraced herself; though she suspected 13:23 was far from her best potential Personal Best. (But easy to remember, being her street address turned inside-out.)

She made some initial observations of her teammates during that time trial, and would fill in some blanks about them over the next two months.

For Lisa Lohe, coming in first was of overriding importance. This applied not only to sports but grades, ballots, milestones (leg-shaving, bra-donning, period-getting)—and even gossip: Lisa had to be the first to hear good news from her friends or slander about her enemies.

Just how much satisfaction Lisa derived from this was an ascetic mystery. Vicki would watch her run an individual trial, her narrow face a rictus of exertion, veins standing out on her narrow neck, and see no thrill of victory when a goal was achieved. Far more likely was the agony of defeat—from falling a few steps behind or going a few seconds over a clipboard-goal. Vicki admired Lisa Lohe, and tried to avoid her.

Rhonda Wright could move like the beep-beep! emblem on her tanktop, often reducing Lisa to Wile E. Coyote woe. The other girls would chant “Road—runner, Road—runner,” as Rhonda zoomed exuberantly past. She also took the lead in cracking jokes about her unique status on the team—such as that her people were accustomed to outrunning packs of white folks, and having natural rhythm was a many-splendored thing. Vicki never knew whether to laugh at these sallies or smile sympathetically, and so tried to do both.

(“Honey, they’re all my brothers!” Rhonda guffawed when Vicki got up enough nerve to ask on Joss’s behalf.)

How anyone with a name as lovely as Yvette could stomach being called “Mumbles” was another unsolved riddle. Less surprising was that Mumbles ran like she talked: a fancy-free canter with bursts of hard galloping. She preferred being on horseback than her own two feet, and could indulge this partiality since both her parents were MDs. (The Metcalfs lived on Caravaggio Place in Baroque Vista, and boarded their horses at Pony Paradise Stable.) Since VW lacked an equestrian team, and Mumbles wouldn’t attend an all-girls (no-boys) school like Startop Academy just because it did have one, running cross country was the closest alternative.

Susan Baxter—inevitably “Big Sue” on the same team as little Susie Zane—loved anything that occurred outdoors. She devoted every summer to wilderness adventures: camping, hiking, fishing, hunting, general roughing it under the sun and stars. Big Sue disliked sleeping under any roof except a tent’s, and hated any errand that involved a trip into The City. Her running gait wasn’t as swift as the other freshmen’s, but she made up for that by each stride being as long as a broadjump.

Alex Dmitria proved herself a natural-born gazelle every time she took the track. She had some characteristics in common with Lisa Lohe, yet invariably lined up behind Mumbles Metcalf, who’d been her mentor in grade school. (Snead Elementary—named for George Bernard Snead, developer of the Green Bridge Shopping Center, though boasting a signed photo of Sam Snead on its lobby bulletin board.) Alex went riding with Mumbles at Pony Paradise most Sunday afternoons, and Mumbles was the first to say Alex would’ve made an excellent Cossack.

Britt Groningen, contrariwise, attached herself to Lisa Lohe’s coattails—though not to her apron strings. Vicki seldom knew what to make of Britt, since Britt seldom wore the same persona two days in a row. Just as she seemed to discard her silken running togs after wearing them but once, so did she fluctuate from Subdeb of the Netherlands to obsequious brownnoser to mystical acolyte to freckly smart-aleck. Lisa might count on Britt as a disciple and adherent; but if Vicki were Lisa, she wouldn’t let down her guard for more than a second. You only had to glance at Britt Groningen to hear the theme music from Jaws—some of the time, anyway.

Glance at Sheila Quirk and hear an all-night Irish slip jig. She came from a clan even huger than the Waltons, and claimed that every time a child of theirs began parochial school at Archbishop Houlihan, the nuns would moan: “Saints preserve us! Is it another of you Quirks??” When the recession struck, Mr. and Mrs. Quirk ran short of tuition funds and gave their children the option to switch to VW. Sheila-Q (who wouldn’t answer to “Quirky,” a nickname that’d been done to death in her household) jumped at the chance:

“I just knew there’d be a better selection of guys here—all kinds, right? Like going to school in a candy store, right? So who’m I going with?—another ex-Houlihanian!” (Snake Oiler, alias Roy Hodeau, who left grease stains on Sheila-Q’s shirtfronts and pantseats.)

“Um, y’know, don’t you think you could maybe do, like...”

“What? Better? Better’n Roy Hodeau? You bet I can!” Sheila-Q beamed Mary Ellenishly. “And don’t I let him know it, too!”

Susie Zane and Laurie Harrison turned out to be stepsisters. They’d actively conspired to unite Susie’s dad with Laurie’s mom, and now contentedly shared a bedroom. Little Sue was a year younger in age (and younger than that in appearance) yet she played the big-sister’s role in their relationship; Laurie looked up to her in every way except literally. She was dependent on Susie for advice, stability, even protection. Attractive enough as a bunny-girl to be preyed upon by cads and rotters, Laurie could (and did) thank Susie for saving her from multiple heartbreaks.

Susie in turn benefitted from having an older kid sister. Laurie insisted she share in every rite of adolescent passage—wearing makeup, getting ears pierced, going on double dates—much sooner than her less-fortunate peers. A lot of Little Sue’s confidence stemmed from having Laurie in her life, as roommate and best friend and number one fan: sweeping away any doubts that Susie would outknockout ‘em all when (not if) she finally blossomed.

While those two were a shining example of kindred spirithood, the Bobbsey Twins covered the other extreme. Karen Lee Bobko and Caroline Appercy had loathed each other from the moment their expectant mothers became bosom chums in an obstetrician’s waiting room. Born a few days apart, deliberately given similar first names, raised side by side (the Bobkos moving into the Appercys’s neighborhood) in identical bassinets, they’d spent twelve futile years trying to convince the world they were not and never would be each other’s dearest pal.

A grim sort of Defiant Ones association evolved, with both Bobbseys counting the days till they turned eighteen and were free to separate forever. Till that glorious time came, they grudgingly participated in all the activities their chummy moms made them do in tandem. However, a permanent record was kept of each annoyance suffered by one Bobbsey and gleefully witnessed by the other, whether or not the other’d caused it to happen. For instance: Karen Lee exhibited baa-lamb delight when their homeroom teacher misread Caroline’s surname as “Appleseed” (which Caroline could not abide). The very next day, Caroline got to rejoice when Karen Lee’s lap was daubed by magenta paint in Art class, due to Terry Blitstein being a butterfingered idiot.

“And him your own sweetiepie!” Caroline jeered.

“We are not ‘sweetiepies,’” Karen Lee sheepishly insisted, tying a jacket around her waist. “For the millionth time, Terry and I are Just Good Friends.”

“Hunh! Just Good Friends don’t give you a crimson crotch!”

“Oh, like any guy’d go anywhere near your crotch—and besides, it was magenta!”

*

Following the first time trial, Mr. Heathcote led them through a cooldown routine. Then he distributed a sheaf of paperwork (with Lisa Lohe flourishing her clipboard); urged them to recruit additional runners from their Gym classes; announced their first official practice would start Monday afternoon at precisely 3:30 p.m.; and dismissed the team with a final PHWEET.

After all that, Vicki wouldn’t’ve minded walking home.

But Alex, planning their Monday pre-school run, wanted to see where she lived; and playing pedestrian with Alex Dmitria meant doing The Hustle nonstop. Even when checking traffic before crossing a street, Alex would mark time with arms pumping and knees up high; so Vicki did likewise, trying not to puff or gasp replies to Alex’s ongoing chatter:

“I guess we lucked out getting Mr. Heathcote as coach, but I sure tried to coax Ms. Swanson into doing it after Miss Gibb had to leave. She said (Ms. Swanson I mean) that she’s too busy gearing up for basketball season even though that doesn’t start till cross country’s over with, and I know for a fact some girls didn’t sign up today just because we’ve got a man for our coach. Like they’re afraid he’ll barge into the locker room and, y’know, hang around with us or something—”

“He won’t, will he?” Vicki gasped.

“Oh I’m sure he’ll knock first. There’s my Papa’s store—” said Alex, waving at Double-A Sporting Goods as they jogged through the Green Bridge. “Have you been in it yet? Well don’t shop anywhere else, we’ve got the best of everything and I’ll make sure you get a discount.”

“Thanks!” Vicki puffed.

“Oh don’t mention it, that’s what friends are for not to mention teammates. Let’s go this way—”

Across the Bridge, take a left on Bedeguar and run (Alex ran; Vicki had to sprint to keep up) past Cedarapple, Velvetleaf, Nutsedge, Foxtail, Scotchbroom, to Sprangletop Road. Marking time with knees up high, Alex pumped one arm and waved the other down Sprangletop toward an exotic specimen of Mission Revival architecture.

“That’s our house, isn’t it neat? I want to have you over when we’ve got more time, well all the girls on the team of course but you’ll be the first ‘cause you live the closest.”

Relatively speaking. Back to Foxtail, then leg it northward past Pearlwort, Jimson, Yarrow, Lesser; Alex chattering continuously, hardly taking a breath despite the fact they were going uphill. Asking what other extracurriculars Vicki would be involved with—reeling off her own lengthy catalog, plus an additional list of non-school pursuits—till you had to wonder whether she’d budgeted any time for minor things like sleep.

“I hope you’ll try out for basketball—”

“Me??”

“Oh I’ve seen plenty of girls your size who can play the game, it’s how you move not how tall you are—”

“I’d have to climb” (puff) “on your shoulders” (gasp) “to make a basket!”

They reached Burrow Lane and found Felicia scowling at the state of the front garden. Vicki (after refilling her lungs) presented Alex, whose radiance must’ve been restoked en route; Felicia blinked bedazzledly as Alex pumped her hand.

“Won’t you come in for a cool drink?”

“Sure will—oh YIKES!” went Alex, with a frantic look at her wristwatch. “Ohmygosh it’s almost two! I’m gonna be late at the animal shelter!”

“Do you need a ride?” Felicia began, but Alex was already hightailing it out of the cul-de-sac—running politely backwards:

“No thanks Mrs. Volester I’ll take a raincheck on that cool drink see you again real soon oh Vicki I’ll be by Monday about 7:15 put all your stuff in a knapsack that’s what I do and it’s a good idea to pack a towel very nice to meet you bohhhhth...”

Around the corner and out of sight.

“My goodness!” said Felicia. “That girl looks like a young Audrey Hepburn!”

She does not! Vicki nearly protested, before remembering Audrey wasn’t the one with the la-de-da cheekbones Vicki’d never liked.

“What was all that about packing towels in knapsacks?”

Vicki explained before going indoors, phoning Joss to let her know she was home, and taking a shower while Joss biked over from Jupiter Street.

After giving capsule lowdowns (the sort Joss relished most) on her new teammates and their boyfriends and Mr. Heathcote the Minute-and-a-Half Man, Vicki went into super/sub mode. During the summer, she and Joss had developed a private means of parallel communication: part body language, part “vibes,” it allowed them to introduce distinct subtext to spoken dialogue. Thus if Goofus happened to be eavesdropping, he would hear Vicki super-say:

“So, Alex Dmitria? She lives pretty close to here, like six blocks down and four over, and she asked if I wanna go running with her before school—to school, y’know, so we’re gonna try it on Monday. Do you have a knapsack I can borrow, to put all my stuff in? She’s like the busiest person on the planet, Alex is—belongs to every club at VW, rides horses, takes care of sick dogs and everything. But if she ever has like a free afternoon, y’think maybe we could hang out with her?”

Joss alone heard Vicki sub-say:

I don’t want you to think I’m “drifting away” from you, that will never ever happen in a thousand years, but Alex really IS “ultranice” and practically a neighbor and I bet we—that is, me ‘n’ you—could have some good times with her. But if you’d rather not give it a try, I’ll just stick to running with Alex and leave it at that.

Similarly, Joss could be overheard super-replying:

“Sure, sounds like fun. I can’t wait to see you two come charging into VW, like across a finish line. Be sure you wear your shortiest short-shorts.”

While only Vicki heard her sub-uttering:

Don’t be silly, I want you to have lots of friends, I’M sure as hell not gonna run to school with you, and of course I know you’d never pull a Kimmy Zimmer on me. But just the same I’m glad you asked first, and though we’ll play it by ear with Alex, I reserve the right to yank the plug on any dy-no-mite “good times.”

With that super/sub-said, they resumed their regular tête-à-tête already in progress.

*

In later years Vicki would say she’d helped invent the school backpack, and had lost a fortune by not patenting the idea in 1975. Certainly she and Alex stood out from the crowd on Monday morning, racing up the eighter staircase with knapsacks on their shoulders.

“What do you need a knapsack for?” Ozzie’d asked. “Did you go out for cross country or mountain climbing?”

A little of both. Running to school had drawbacks, especially after you got there. Lucky thing that Phys Ed was first period, giving you an adequate chance (thanks to Becca Blair) to clean up afterward, throw on a good top and skirt and touch of cosmetics, and make it back to Z-Wing before Miss McInerney started splitting infinitives. But what an embarrassment to enter homeroom looking less than your best—damp with perspiration, despite the towel Alex had wisely suggested bringing—and then have to sit there in starkly uncute contrast to Carly Thibert.

(Vicki limited her recuiting efforts to Carly, since there was no point re-asking Joss or Robin or Fiona. And Carly lost interest when informed there were no boys on the girls cross country team. “If you had boys, you wouldn’t need knapsacks,” she reasoned. “That’s what boys are for—to carry your books. That, and—giggle!—other stuff.”)

(“This is how the Marines train, running with loaded backpacks,” said Alex. “And their backpacks are loaded with bricks!”)

Vicki might not be ready to enlist in the USMC, but after a week of running knapsacked to VW, she no longer gasped or puffed upon arrival. The afterschool practices helped too: from 3:30 to 4:30 Monday through Thursday plus noon on Saturday, these were designed to build up stamina and endurance. Various lengths were run at varying speeds; long steady lopes alternated with faster-paced sprints. Only thirty seconds of rest between 220-yard dashes; a minute between quarter-miles; two minutes between half-miles.

Mr. Heathcote warned them not to try increasing their mileage too rapidly. “Learn how to control your breathing—how to keep an even pace—achieve consistency—and always persevere.”

No complaints about bad weather were permitted. You ran in rain; you ran

through mud. If there was an early cold snap, you ran in sweats and caps and

gloves. You ran on grass, dirt, concrete, asphalt. You learned how to keep

going when you felt dog-tired, by focusing on your form—and that of your running

buddy, for which you were as responsible as your own.

Vicki was paired with Sheila Quirk, whose company she enjoyed, even though S-Q could run with all her Mary Ellen Walton hair blowing loose in the wind, and not get slowed in the slightest. Vicki’s own tresses were so long by now that if she didn’t braid them beforehand, they would drag her around like a parasail when the wind blew off the Lake.

“Check out Britt hogging the sidewalk,” Sheila-Q snortled one afternoon.

“How does she do that?” wondered Vicki. “She’s littler’n me!”

They watched Britt outflank her running buddy Karen Lee Bobko—to the left, to the right, down the middle. Karen Lee might be able to cope with Caroline Appercy, but she was totally out of her depth in Britt Groningen’s tidepool.

“Her mouth isn’t littler’n yours,” said Sheila-Q.

“Aw,” went Vicki, who often worried that her mouth was too wide; lipsticks seemed to get used up awfully quickly. But she knew what S-Q really meant, and fully agreed. “D’ja hear her badmouthing Mumbles before warmup?”

“Does she ever goodmouth Mumbles?”

“She goodmouths Lisa—to her face. Not so much behind her back.”

“With Moana Lisa, how can you tell which side is which?”

“Let’s take it on home, ladies!!” yelled their captain from the head of the line.

“Lord!” went Sheila-Q.

“I know,” said Vicki as they quickened their pace. “I mean, I really like Mumbles and everything, but our eardrums.”

“And it’s not like we’ve got spares.”

Kick it up for the final 220 with a mutual “Beat Britt,” their standard end-of-buddy-run vow. But by the time they caught up with Groana, she’d already started her cooldown with Moana, leaving Karen Lee looking extra sheepish.

“Hold on, you guyyyys,” Mumbles was telling them—or seemed to be, at drawl-volume. “We’re supposed to do cooldowns as a teeeeam.”

“Sorry? Say what? Can’t hear you, chief.”

(This from Groana. Moana slowly froze in mid-stretch, looking mid-pinched.)

Mr. Heathcote had told the team to elect a captain, subject to his approval, stipulating only that it must be one of the ninth-graders. Rhonda and Big Sue promptly took themselves out of the running, saying they were there to run but not run things. So Britt nominated Lisa, Alex countered with Mumbles, and each delivered a sixty-second speech.

Or, in Lisa Lohe’s case, a sermonette. Cross country was part of a higher calling: to climb life’s mountain (wearing a knapsack?) and attain not simply a Personal Best but perfection. Yes, every step might be a lonely challenge, but one that could be overcome by making a 110% effort and accepting nothing less. Do that, and we’ll all be winners.

The team then dealt with the challenge of listening to Yvette Metcalf—leaning in to hear the drawlier parts, rearing back during the shoutier. We’re gonna work haaaard, and we’re gonna play haaaard, and we’re gonna haaaave ourselves an outtasight long-distance BALL! HA!! HA!! HA!!

She and Lisa stepped out while the other girls deliberated. It was felt that Lisa’d be more inclined to find fault than things to praise; the team’d probably never be deemed good enough to carry her clipboard, much less climb Mount Perfection. Mumbles, on the other hand, would be more encouraging and supportive (at the cost of a few eardrums) and maybe with her in charge, they could still get other runners to sign up.

So Mumbles won 6-to-4, backed by all the Z’s and Y’s except Caroline, who (to spite Karen Lee) voted with the X’s for Lisa. Having discharged their X-duty, Rhonda and Sheila congratulated the new captain; Britt sleepy-smiled like a hatchetgirl honing a blade; Caroline copycatted Britt; and Lisa, binding herself to a martyr’s stake, became Moana of Arc.

But she stuck with the program, as did the rest of the original dozen. None of their recruits, though, stayed for more than one practice; they found cross country too exhausting, too time-consuming. Mr. Heathcote talked a lot about Proper Time Management—how you had to put schoolwork first while not “sloughing off” training (which invites injuries) or getting less than eight hours of sleep every night.

Vicki couldn’t help but peek at Alex Dmitria every time this was mentioned.

Alex came by Burrow Lane every weekday morning without fail. She and Vicki ran to school together; met up again in Phys Ed; raced to English with Becca Blair, respectfully defying Vice Principal O’Brien’s orders to not run in the hall; waved Hi in Vocal Music. And that was the extent of their friendship: Alex never had leisure to spare, never loitered at Vicki’s house longer than to swig a glass of water or juice while Vicki secured her knapsack.

She always pledged to return sometime for a good long visit, get to know all the Volesters really well, have Vicki over to the Dmitria home just as soon as things let up a bit. Vicki offered to come by and meet Alex there some mornings, but oh no thanks I really need the extra mileage—hey we’d better get a move on don’t want to be late—thanks so much for the OJ it was delicious—

Vicki’s feelings might’ve been hurt, had she not seen Alex act the same way with everyone else. Even Becca, even Mumbles; hyperactivity always took precedence.

Not so for laidback Joss Murrisch.

She joined the VW Brass Ensemble, which rehearsed after school on Mondays and Wednesdays. On Tuesday and Thursday afternoons she hung around the Media Center, studying or listening to tapes. All four days she’d wait for Vicki to finish practice, then escort her home—Vicki gamely jogging (“Never walk when you can run”) while Joss demonstrated just how slowly she could ride a bicycle. Most Friday nights Joss slept over at Vicki’s, and got driven by Felicia to her Saturday cornet lesson. Vicki, after that day’s cross countrying, would run or bike the three miles from school to Jupiter Street, and zonk out there most Saturday nights.

Thus she and Joss nurtured their friendship, keeping it freshest and best, while not barricading the garden against others who might drop by.

“Um hi, you guys—okay if I sit here?” Laurie Harrison asked one lunchtime, clutching a tray and looking adrift as she tended to do when Susie wasn’t around to provide ballast.

Joss and Laurie were already longtime classmates: they’d been in the same room for most grades at McGrum Elementary, and Laurie’d witnessed the rise and fall of Joss’s bond with Kim Zimmer.

“So,” Joss asked her, “how’re things back in the old Y-Wing?”

“Better’n for us in Z, I bet!” sniped Robin Neapolitan.

“Well okay, I guess,” Laurie offered, edging her stool away from Robin’s, and averting big brown bunny-eyes from Fiona Weller’s spectral stare. “We all miss you, Joss.”

“All?” Joss scoffed. “Sweet but untrue. I could name a couple exceptions who didn’t cry themselves to sleep when I transferred.”

“Um well, about them,” Laurie began, pausing to deal with a mouthful of lettuce. “Vicki, can I ask you something? Don’t take this the wrong way, but is it really true—that is, y’know, if you don’t mind my asking—I mean...”

“Gahd, Laurie, what??”

“—were you really in a gang when you lived in The City?”

Metcalf-caliber laughter shook their cafeteria table, and milk actually shot through Robin’s nose.

“Shhnnnnit!” she reacted, causing a jocular aftershock.

“I’m sorry,” Laurie quailed, but everyone except Robin assured her this was a noteworthy accomplishment.

“(Means it’ll be a lucky afternoon,)” explained Fiona.

“Okay, so who spilled the beans about Vicki’s wicked past?” Joss demanded.

“Joss!” went Vicki.

“No, it wasn’t me. ‘Fess up, Laurie—you heard that from Kim Zimmer, right?”

“She didn’t tell me,” Laurie hastened to say. “Like Kim’d ever talk to me. But well, I kinda think, that is, she might’ve said something like that to, um y’know... Gigi Pyle.”

“Typical!” humphed Joss. “Gotta admit, though, this time she’s absolutely right—”

“Joss!”

“Yep, you’re looking at Guadalupe Velez—that’s her real name. (We don’t have to keep it a secret anymore, Vicki.) They used to call her ‘Loopy the Enforcer’ when she ran with the Pfiester Park Pherrettes—”

“Will you shut UP?” Vicki howled. “Gahd, Joss! Ferrets? What kind of gang name is that?”

“Better’n Ladybugs,” said Robin, still wiping her strawberry face.

All female sports teams at VW were called the Ladybugs. Feminist jockettes thought this childish if not demeaning; girlier ones (like Laurie Harrison) reveled in the title.

Or at least they did till squat Roger Mustardman got hold of it. To the tune of “Rag Mop”:

|

L! L, A, D, Y! B, U, G—B, U, G, S! L, A, D, Y, B, U, G, S— LAID-BUGS!!! |

Followed by a variation on “Lydia the Tattooed Lady”:

|

Ladybugs O Ladybugs Say have you seen Ladybugs? Ladybugs run GIR-ulls cross country! They have legs that flash like lightning And their speed’s completely fright’ning... |

Although Mr. Heathcote posted their practice schedule for anyone to see, they were always startled to find Roger Mustardman lurking along the route du jour. Very soon he was accompanied by Lenny Otis and Dino Tattaglia, on the routes and in his chants. One day they even climbed a large tree on Oakapple Road, to “roto-root” from overhead as the L-Bugs passed below.

“HA!! HA!! HA!! (Ignoooore them,)” ordered Mumbles.

People started calling this trio the Smarks Brothers. Which reminded Vicki of the Three Marks back in kindergarten—one tall, one short, one dumb, all obnoxious.

Roger had a special knack for baiting Robin Neapolitan into speechless frenzies. They were studying causes of the Revolutionary War in Social Studies, and Mr. Gillies assigned Robin to do an oral report on the Stamp Act. Robin (outspoken about her libertarian Harley-Davidson views) turned this report into a demand for repeal of mandatory helmet laws.

Mr. Gillies asked the class for commentary.

Roger raised a hand. “So, was Gregg Allman quoting Samuel Adams when he wrote ‘Midnight Rider’? Like when he says ‘I got one more silver dollar,’ or was that from George Washington across the Potomac? And that line about ‘the road goes on forever’—do hobbits ride Harleys? Did Bilbo Baggins oppose paying for stamps, or just licking them?”

“That’ll do, uh Roger,” said Mr. Gillies.

Roger nodded penitently and turned to Lenny Otis. “Hey, is that Bilbo’s ring you’re wearing?”

“Uh huh!” chimed in Lenny. “‘I met him at the candy store! You get the picture?’”

“‘Yes we see,’” Roger responded. “‘That’s when we fell for the Stamper of the Act.’”

Mr. Gillies terminated their rendition, but at lunchtime Robin was still frothing at the mouth.

“Seriously, you can’t let him get to you,” Joss cautioned. “You’ll bust a blood vessel or something.”

Which seemed imminent as Dino Tattaglia arrived at the Smarks Brothers table, heralded by “HE’S A PIMP!!” from Roger and Lenny. “That’s pimp, not pimple,” Roger added, waggling eyebrows in Robin’s direction.

“What IS it with him?” Robin snarled.

“(Obvious,)” offered Fiona. “(He’s warm for your form.)”

“OH! GROSS!” gagged Robin. “You take that back right now if you expect me to ever buy milk for you again!”

“(Who’m I to deny a guy’s passion?)”

“What guy’s passion?” asked Sheila Quirk, plunking down between Vicki and Laurie. Sheila-Q played the flute, so Joss and Robin and Fiona knew her from Band, but they hadn’t talked to her that much before now.

“Roger Mustardman—the one over there, in the glasses,” said Vicki.

“(He’s got the hots for Robin.)”

“Will you quit saying that out loud??”

“Mustardman, hunh? I know all about him,” said Sheila-Q, digging into her macaroni salad. “Family’s got a lot of dough—big house on the lakefront.”

“Do they sell mustard?” asked Laurie.

“Nope—they’re major-league plumbers.”

“And live in a house by the Lake?” went Joss.

“With a mind in the sewer,” frothed Robin.

“Pretty much,” Sheila-Q nodded. “They say Roger got kicked out of Front Tree after sixth grade, and I know he tore up 7-X last year with Dino Tattaglia. They started assigning themselves detention, ‘to save time for the teachers.’ That’s how you lucky Z’s got him this year, Roger that is—we still have to put up with Dino in 8-X. Who’s the googly-eyed guy with the fright wig?”

“Him? That’s Lenny Otis.”

“(Says he’s the reincarnation of Lenny Bruce,)” added Fiona. “(Goes around yelling ‘Two thousand tubes of airplane glue!’)”

“Cute.”

“Ooh, Sheila!” squealed Laurie.

“Really! What’ll Roy say?” wondered Vicki.

“I didn’t mean he was,” Sheila-Q spluttered, while Joss began to plan how S-Q and Lenny could double with Robin and Roger—“Somewhere elegant, y’know, like Bowling for Dollars”—till both girls were ready to take a sock at her.

“We’re trying to like eat here!”

“Honestly!”

“Hey lookit,” said Laurie, directing their attention to the Smarks table. Over which Britt Groningen was now hanging.

“Gahd,” went Vicki.

“Really!” Sheila-Q concurred. “Believe me, Britt can do better.”

“Is she as big a bitch as I hear she is?” asked Robin. “I hope so! I hope she’s the Queen Bitch, and makes Mustardman fall the hell in love with her, and leads him on and teases him crazy and then dumps his blue balls in front of the whole freaking school!”

“(Sounds like somebody’s jealous,)” remarked Fiona. Who avoided a sock on the arm only because the bell rang just then.

*

Thursday the 2nd of October. A coolish afternoon, but clear and dry.

A school bus crossing Chubb Avenue into Athens Grove, west of Vanderlund. Heading for Timonoff Park and the Ladybugs’s first dual cross country meet.

First meet, but second visit to Timonoff Park: they’d gone there last Saturday to check out the course. 1.5 miles—2640 yards—2400 meters—up Eureka Way, around the Timonoff Fountain, and back via the Kasseri Trail. Mr. Heathcote led them around once at a steady jog, pointing out significant features; then sent them around again at race pace, critiquing performances and suggesting improvements.

By now everyone’s particular strengths and weaknesses were fairly well documented, and the latter addressed. Lisa pushed herself too fast too soon; Susan had problems kicking it up in the home stretch; Laurie could run like a jackrabbit, sometimes, but got discouraged too easily; Vicki was overconscious of her Klumsy Klutzer past, and kept reliving it with stumbles. Alex tied herself into unnecessary knots; Rhonda believed a pastime like running shouldn’t be “practiced into the ground, honey!”; Susie couldn’t understand why her future potential didn’t translate into immediate results; Caroline and Karen Lee sometimes (okay: often) seemed interested only in compelling each other to eat her dust. Mumbles, while unfailingly well-disposed, could make even a “great job!!” or “nice pace!!” painful to hear; and Sheila-Q habitually swore she’d never been told anything she didn’t want to listen to in the first place.

As for Britt, Mr. Heathcote had issued repeated warnings that any interference with competitors—be it physical contact, causing them to break stride, or trying to block them from legally passing—would result in disqualification.

Yet they’d trained as a team, helping each other to improve, as their numerous time trials could attest. And now they had a common foe: the Lady Arcadians of Athens Grove Junior High, who outnumbered VW’s girls eighteen to twelve, and were clad in uniforms of blue and white. Ladybugs, naturally, wore red and black: gallant honorable colors, though you had to be careful laundering them.

The L-Bugs studied the Arcadians, picking out their Four Genies of the Apocalypse—Jeanne, Gina, Jeanine, and Jeannette—who were putting Athens Grove on the cross country map. (Though none of them had light brown hair.)

“Hey, there’s Frieda!” said Big Sue, jolted out of her usual taciturnity. “Rhon, look—it’s Frieda Pieper!”

“Man!” went Rhonda. “She looks like a zombie chick. I’da thought they’da moved way farther away than Athens Grove.”

“This is bad, you guys,” moaned Lisa. “Frieda was the fastest runner VW ever had, the very fastest. We’ll never beat her.”

“C’mon, everybody, waaaalk it off,” drawled Mumbles. “Focus on our warmup.”

Vicki, while stretching conscientiously, took several ganders at the famous Frieda. Who did seem stupefied by all the upheavals she’d had to withstand since July—and might be desperate for an opportunity to flee from them, trampling roughshod over the team she was supposed to have led.

(Ouch.)

Warmup done, Vicki surveyed the meager troupe of spectators and was rewarded with a glimpse of light brown hair—not one of the Four Genies, but her own freshest-and-best friend. So Joss had made it (thank Gahd!) brought by Felicia and probably Goofus; Ozzie too had vowed to leave the Lot early and catch her in action. Other parents and siblings were also present: Susie’s dad and Laurie’s mom, some of the Quirk clan, whichever Dr. Metcalf wasn’t on call; maybe one of Rhonda’s brothers for Joss to entice. The L-Bug Auxiliary ought to be there too—Roy Hodeau, Babyface Nelson Baedeker, and Terry Blitstein (Karen Lee’s Just Goonish Friend).

Plus, no doubt, the Smarks Brothers. Yes: Vicki could hear the ooh! ooh! of Lenny Otis. Had he acted like a Horshack even before the premiere of Welcome Back, Kotter? Why was she thinking about a thing like that at a time like this? To keep her mind off her big fat feet, that’s why—the image of them tripping over each other, making false starts and feeble finishes.

“C’mon, you guys, all together now! This is it!” chattered Alex.

Mumbles extended an arm, palm down; Alex clapped her hand over the captain’s; the other ten L-Bugs piled theirs on top.

“Go-o-o-o-o Vanderlund!!”

Their battle cry was answered not by Athens Grove, but a Smarksist perversion of The Student Prince’s drinking song:

|

Britt! Britt! Let the chase start! Lay-dee-bug breaks your heart! Britt! Britt! Britt! Let ALL Roto-ROOTers say SHE Will go faaaaAAAARRRR— |

(Unclear whether they ended that last line with an R or a T.)

“Gee, Britt!” Lisa masticated. “Who’re we supposed to be—You White and the Eleven Dwarves?”

Sleepy sigh, followed by a Groano Ono haiku:

|

Oh Lisa, you think Clowning makes a difference? And besides, it’s dwarfs. |

Just enough time for Vicki and Sheila-Q to trade “Beat Britt” vow-nudges before the starting gun.

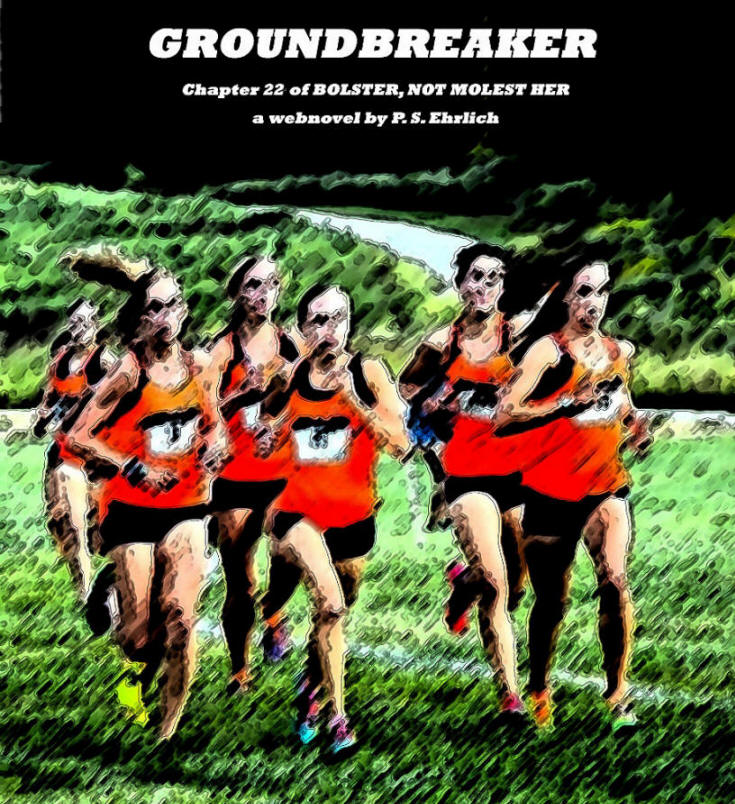

And they’re off. We are; you are. Fast but not too fast to begin with; nobody wins by wasting energy on the first quarter-mile. Run strong, keep it even, stay on pace while you jockey for position in the pack. Some are far ahead by now, red shirts you recognize: Rhonda the Roadrunner and Alex the Gazelle, Susan plowing up the turf and Lisa pumping furiously through blue-shirted obstructions. No sign of Britt, but S-Q’s right there matching you stride for stride as you leave Eureka Way, swing round the Fountain and head for the Trail. Thankful it isn’t raining; neither of you are good mudders, and the Kasseri Trail’s all dirt.

This is what it boils down to: a month of training, of avoiding Zephyr Heaven, of no milk or pop or junk food but fruit and veggies and all that pasta for the carbs, all that water! water! everywhere! to keep you hydrated not to mention inside washrooms when you aren’t out running, and when are you not out running? hour after hour, day after day, breathing deep and slow through nose and mouth, staying straight and smooth with every step, hoping you can really do this—hope so? know so—acting relaxed as you pass one blue shirt and then another, making them think you’re daisy-fresh and can run faster forever, making yourself think that as you leave the Trail and launch your final kick, chest hurting, lungs bursting, keep on going don’t quit now never give up finish the race oh no you don’t you skinny-assed Arcadian you’re not about to pass me—

I am a butterfly: I

float, I glide.

Run run run LEAP.

With a flawless grand jeté: soaring past the skinny-assed competition and over the finish line.

Into the chute then, single file, nearly colliding with Mumbles ahead of you. Being told to keep walking, keep your head high, unlike some of the girls who were doubled over or staggering on rubber legs—Lisa Lohe having to be held up by Susan and Rhonda, Mr. Heathcote watching her closely, an anxious spectator calling Lisa’s name, her mother maybe, narrow-visaged like Lisa who would do a thing like that to herself, bolting at the beginning into agony at the end.

All in less than fifteen minutes.

“M’okay, m’okay,” Lisa gasped. “How’d we do, did we win? What was my time?”

“Sweats on,” Mr. Heathcote commanded the other L-Bugs. “Cooldown now—results later.”

A cross country team is scored by where its first five runners place, with the lowest total winning the meet. Ideally yours would be the first five across the line: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 equals 15, a perfect score. Your sixth and seventh runners are also awarded points—not added to the total, but they can displace slower opponents. So if your girls were the first seven to finish a dual meet, the other team would score 8 + 9 + 10 + 11 + 12 for a dismal 50—the worst possible total.

In the meet at Timonoff Park, the Four Genies of the Apocalypse finished 1st (Jeannette), 3rd (Jeanine), 4th (Gina), and 8th (Jeanne).

The first five L-Bugs were Rhonda (2nd), Lisa (5th), Alex (6th), Big Sue (7th), and Mumbles (9th).

Vicki’s grand jeté—which she expected Mr. Heathcote would call “overstriding,” a cross country no-no—landed her in 10th place, displacing no less than Frieda Pieper to Skinny-Assed Zombie Chick (11th).

Final results:

Athens Grove Lady Arcadians 1 + 3 + 4 + 8 + 11 = 27

Vanderlund Ladybugs 2 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 9 = 29

Winner: Athens Grove by two points.

Fresh agony for Lisa. Sheila-Q, who finished 12th, literally kicked herself for not keeping up with Vicki and further displacing Frieda; though the L-Bugs would still have lost. (Britt, who came in 19th, basked in the extraordinary feat of outpacing Laurie and the sevvies.)

Vicki came out of it with a new Personal Best—1.5 miles in 11:58—and momentary immortalization, thanks to finishing-line photos snapped by Joss and Ozzie. There, caught on film from two different angles, was proof positive she’d taken five years of ballet lessons.

“You shoulda seen your face!” Joss had exclaimed after the meet; and now Vicki could, along with everyone else at her cafeteria table. If there really had been a gang called the Pfiester Park Pherrettes, and their sergeant-at-arms really had been “Loopy the Enforcer,” she’d’ve had the exact same dagger-dangerous expression as Vicki doing her aerial split.

“Wish I could leap like that,” sighed Laurie Harrison.

“You’ll be unstoppable on the hurdles when we run track in high school,” declared Alex Dmitria. (Alex liked to circulate the lunchroom, eating with different groups of her many friends, and today she was sitting with Vicki’s.)

“If you can pull off one of those every time, I’ll start going to your races,” promised Robin Neapolitan. “Okay now, where were we? Oh yeah!—”

She and Sheila Quirk had begun having epic arguments, starting these during first period Band, then picking up at lunchtime where they’d left off; occasionally switching sides to see how well they could argue from the opposite viewpoint.

Today’s topic was Rocker of the Year: Robin saying Bruce Springsteen, Sheila-Q holding out for Paul McCartney. (Fiona Weller insisted both were wrong—no one could outshine David Bowie.) As per usual, voices were raised on both sides and tempers teetered on the verge of being lost.

“Baby we were born to run!” proclaimed Robin.

“Listen to what the man said!” retorted Sheila-Q.

“F-A-A-A-A-A-A-A-M-E!!” thunderclapped Fiona, of all people; and a hush fell over the dumbstruck cafeteria.

Broken by the Smarks Brothers answering, “What you get is no tomorrow! What you need you have to borrow!” and a general eighth-grade laugh-shout.

“(I win,)” concluded Fiona.

*

“We’ve got a pretty good lunch-bunch,” Vicki told Joss.

“That’s all you, y’know.”

“What, don’t you think so?”

“No—I mean yeah, I do—I mean it’s ‘cause of you we’ve got it.”

“What do you mean?”

“You’re like the magnet that’s drawn us all together. If you hadn’t left the Pherrettes and moved to Vanderlund—”

“—will you shut up about that?—”

“—I’d still be marooned over on Y team. I’d still only know Robin and Fiona in Band, and we’d probably still not talk that much to Sheila Quirk. You’d never have seen Fiona and Laurie Harrison eating lunch together. Face it, Vicki—you’re our two thousand tubes of airplane glue!”

“Gluey Guadalupe!” said Vicki. “Hey... do I really look like a Guadalupe Velez?”

“More’n I do,” said Joss.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Return to Chapter 21 Proceed to Chapter 23