Chapter 9

Second Wind

I walk out of Selfsame into a Chirico landscape. Brooding, ominous, enigmatic, dismal. Jackdaw Square is almost deserted—even by crows. A few featureless people imitate distant sundials. Sign over the drugstore says it’s 91º in the shade. And that shade contains streaks of black bile.

(As does my gut. Damned creamcheese.)

Friday the 5th of July. The morning bus was nearly empty; likewise the Selfsame staff lounge. But I went in to work, this being my last Friday here for a long while.

Stop by the gallery. Even Ralph is absent; the only one here is Just‑Hatched Chick. (Feathery yellow hair, fast-blinking eyes, tendency to cheep.) The Crouching group show hasn’t been taken down yet—

—but Watch Your Back is gone from its spot on the wall. No sign of title card, price tag, or sold sticker. I look around for The Mute Commute: it too has vanished.

Wait. This might signify nothing more than Double-Bag Eddie’s having dropped in.

“Edgar Clint been here?” I ask.

“Nobody,” cheeps Just-Hatched Chick.

Screw it. Let them hang my pieces, draw and quarter them, prop them in the alley for crows to peck at. I’ll seal off Prized with a coat of oil and layer of wax, glue the medallion into its niche and keep the thing for myself.

Dead low tide outside. No fluttering Maytime breezes today. The river exhales summer nox from the South Bottoms, where Slaughtertown’s stockyards and packing plants used to thrive.

Too Bad God Almighty Just Lost Interest.

Wish I could do the same. Last night I had the unboarding dream again. Hacking my way through wilderness to a wall overlaid with rough pine planks. Prying these loose, feeling the boards splinter, hearing the skreek of each rusty nail. Opening a window onto inky night. Straining to peer through it, see what might be afoot, when bang and flash—

—to reveal an enormous panther dragging her body away, fangs sunk into her throat.

(Thank you, Ambrose Bierce.)

I got out of bed and called her. Today too, from Selfsame. The phone at Sycamore Terrace rang and rang with no switchover to the answering machine, though power must’ve been restored long since. Meanwhile there’s a constant busy signal on her cell.

I knew she wouldn’t be on the #104 this morning, but looked for her even so. Will just as likely crane my neck when the p.m. bus reaches Figure Eight Way. What I ought to do is drive to Knotts and size things up. Find out where she’s gone and try to follow.

If I were the one who was hiding, wouldn’t she seek me?

So why this reluctance?

See myself approaching D9. Finding my path blocked by prowlcars and ambulances, crowding round a lacerated body in a pool of blood—none of which would be there if I didn’t make them happen—by going up there and rocking the rope.

Not even a rope: a thread, by which we’re hanging over thin ice.

Say I drop by Downy Owl Road. Suppose Sleepy LeThean denies having hired her, being impressed by her—any memory of her at all. “What are you talking about, Aitch? You’d best stay out of the sun. Let me show you some cocobolo from Costa Rica...”

Chase a delusion and what happens? You could topple it over the edge, the False Madeleine along with the Real Judy—send them plummeting off together to leave you bereft and bereaved.

Better trust your gut instinct, despite the black bile. Step aside, turn away, go home. Even if that does make this the first weekend in two months that you’ll be by yourself.

It’s hard...

In my pocket. In my hand.

Thumb rubbing it, like hers over my palm-calluses.

I take it out and look at it: a wreath of stars. Surrounding four pool lanes topped by wavelets, above which is the upper half of a stopwatch.

Prized’s silver medallion.

She bought it for me at a trophy shop. Proud and glad to be making a material contribution to the artwork, apart from the modeling.

So there you are—tangible proof this hasn’t been just a dream.

Or, at least, that it’s been a substantial one.

*

Four more days I go in to work. On one of them I encounter Nicolette Ningal in Jackdaw Square, and have a sudden wild hope she might consent to play my rebound girl. But Nikki just tugs an earlobe and says, “I’ve heard that one before.”

Pity. I could use a Moon Maid right now.

Friday the 12th. Bags are packed. I’ve bubblewrapped Gatherin’ Stormin’ and Plue Velvet, Frieze-Frame and A Perfect Fit. Artificialities I’m leaving behind, but the unfinished Prized is coming along, plus a dozen blank panels and that spare block of cherry.

The Old McRale Place awaits.

Three weeks and a day (to make up for the 5th) I’ll be spending there. I’m trusted to leave the Place as I find it, and to bring back Mr. Wilson’s least favorite truck in no worse shape than it set out in. Even so, Mrs. Wilson hands over her ring of keys with somber gravity, heaving a sigh as though she’ll never lay eyes on it or me again.

I wait till the a.m. rush hour’s over, then slip the surly bounds of ‘burbs and hit the cloverleaf. Fifteen minutes on the expressway and the nox is gone, the gristle’s been rendered, and Demortuis has eaten our dust.

Set your compass west by northwest: precisely 338 miles from garage to Place. Factor in lunchtime and we’re looking at six hours on the road. And not a very eyesnaggable road: got to guard against woolgathering, wits-wandering, and bringing in stray sheaves.

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro’ the field the road runs by, and by, and by...

Up and down the people go. Thro’ fields that gro’ and gro’ and gro’. Corn. Oats. Wheat. All your embryonic breakfast cereals. Too early to think about stopping to graze. Find some digestible music to focus on. Easily done as we approach Keening, a college town like Lawrence and Columbia, and pick up their classic jazz station. Playing Sarah Vaughan’s “Solitude” as we tune in—theme of the day, the week, the month to come.

The past as well. Favorite album of Wendell Jones, my first roommate at Liederkranz. The Lonely Hours, it was called. What else was on it? “I’ll Never Be the Same.” “You’re Driving Me Crazy.” And let’s not forget “These Foolish Things Remind Me of You.” The record would stick there and repeat oh how the ghost of you clings till you wanted to call in an exorcist.

Jonesy was tall and stooped and gawkish and stammery. He turned his half of our dorm room into a shrine to Lucinda Faye, a toothsome blonde back home in Oklahoma, spreading photos and mementos over two walls and part of the ceiling. Cheerleader, choir singer, tennis player, sweater stretcher—lucky old Jonesy, I thought. At first.

Then doubts crept in. Lucinda Faye looked a lot like young Kim Novak in Picnic: a downhome debutante stacked with ennui. But Jonesy was less of a shirtless William Holden than a bowtied Jimmy Stewart. So had he gone Vertigo over her? Or had she cast a Bell Book and Candle over him? Was he given these souvenirs to remember his sweetheart by, or had he “acquired” them somehow from a girl unaware of his existence?

Every week Jonesy would paint another portrait of Lucinda Faye, from bewitching memory or bothersome imagination. None failed to merit a full-frontal rating; but some bordered on the peculiar.

“He is so weird!” said Bonnie Pattering, as close to undelighted as her nature would permit. “What is it with him and her?”

I wasn’t eager to ask.

Especially not at 3 a.m. one November night when I woke to find a soused Jonesy gawking at his shrine by the light of a Coleman lantern.

“Damn it, Wendell...”

Whispering: “D’you think she’s irresistible?”

“Sure, why not? Now turn that thing off.”

“Ought’ve been more romantic. Like gallant knight ‘n’ lady fair. Shivery.” (I think he meant chivalry.) “But she won’t let me take MY EYES OFF HER!!”

“Hey, take it easy, man—”

“Will you assholes put a lid on it??” from the fat guy next door.

Jonesy hoisted a fresh canvas onto his easel. Picked up palette and brushes and set to work by lanternlight. Producing by sunrise an R-rated Night Gallery portrayal of Lucinda Faye, beckoning the viewer with a blurred smile that was, in fact, shivery.

Soon afterward he went home for Thanksgiving and never returned. His belongings got boxed up and shipped posthaste to Oklahoma, including the done-to-death Lonely Hours and everything in the shrine. We later heard that before reaching Muskogee, he’d plowed his Valiant into a juniper tree and impaled himself on the steering column.

No clue whether that was Jonesy’s way of falling on his own sword.

(But Bonnie made me “cleanse” my dorm room by burning parsley in a seashell.)

Foolishness. Bewitchery. Bell Book and Candle, candle book and bell; forward and backward to send Jonesy to hell...

Sarah Vaughan’s faded out of range. High time for lunch. Stop at the soup joint in Beat All Hollow, have a bowl of their famous mushroom chowder—and crack my skull against the doorframe as I climb back in the truck.

yeedge!!

Jerome Gullip must be laughing his damned ass off.

Still, it might dispel a few crop-full cobwebs. Don’t want to get drowsy at the wheel. What doesn’t knock us unconscious makes us awaker, and so forth.

Onramp. Interstate. Chrome and concrete. Hurtle before, hurtle behind, hurtle to left and right. Are we all turtles? Bet our damned asses. You there, are you going to change lanes or not? Try using a turn signal. You in the Land Cruiser: do us all a favor and pull your UV out of your S. You off on the shoulder: a crumpled sedan with shattered windows. Next to it’s a hunched-over sobbing woman—

—calm down, lady, it’s not like you caused the crash—

Bang-flash as I pass by.

Glance at the rearview mirror. Can’t see a thing but traffic in transit. No one slowing down to take a ghoulish-bastard gander.

Maybe there was no wreck.

Maybe I’ll start seeing it everywhere I go, like Val Kilmer and that old roadside Indian in The Doors.

Trompe l’oeils. If not deceit, at least duplicity. Double-crossing. As in that H with the widened crossbar: Dos Equis, joined at the hip. O what a tangled web we weave when first we see what we believe. Takes two to tangle... except that it’s men who tangle; women weave. Transcending duplicity to reach—what? Triplicity? Three sheets to the wind? Three’s porridge hot, cold, in the pot...

(Listen to yourself, for crying out loud.)

What happened to your head, Roadside Indian? “I ran into the Doors.”

People are strange. Mirages are stranger. Better screen all incoming imagery. Screens are meant to have fine women undressing behind them. Or before them. Should’ve had a screen at Green Creek Lane. The Diverting Dozen (plus one) either disrobed in the bathroom, like sluggish Nina Silbergeld, or stripped on the spot like Stormin’ Molly Brown. Either way a screen would’ve added something extra to the scene.

Concealment. Division. Protection. Arousal...

Wooden screen, of course. Three folding panels. Or rather three frames, each containing panels carved separately. Say a couple of 18x24s per frame, six-inch rails top center and bottom, three-inch vertical stiles; the extended screen would measure 72x66. Six panels carved on both sides—no, then I’d be stuck carving basso-relievo, and femininity calls for alto. When it does I want to respond with sculpture, not incisions.

So let’s put a pair of panels back to back. Four per frame; twelve in all. Though they’d make each panel thick as a door.

A screen of three doors...

Maybe that crack on the skull let in some enlightenment. I just happen to have a dozen blanks packed in the truck bed. Not that I could hope to carve them all in three weeks. But glad they’re on hand, given the increasingly treeless landscape out there. Big sky horizon everywhere you look; scrub and brush ad infinitum. An Andrew Wyeth panorama: vast, detached, austere...

O bury me not on the lone prairieee

Where the buzzards sail and the crow flies freeee

O bury me not—but my voice failed therrrre

And they paid no heed to my dying prayyyyer

In a shallow grave only six by threeee

They buried me there on the lone prairieee—

—whoa! nearly missed my exit—

This was Town to Mrs. Wilson when she was growing up as Myrtle McRale. County seat and site of Big Red’s Diner, Old Blue’s Bar & Grill, Uncle Yeller’s Service Station. I pause at the latter to empty my bladder, fill up the pickup’s, scrape three hundred miles of insect roadkill off the windshield.

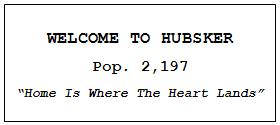

Hot out here. Dry heat, though; better than damp. Hubsker looks a bit more moribund than it did a year ago. The motel across from Yeller’s has gone out of business. “appy l nd” clings to its signboard. All that remains of Happy Landings? Or There Is a Happy Land Far, Far Away?

If so, we’d better resume getting there. Turn onto State Route 65 (one digit away from musical fame) and head south, along with half of Hubsker’s Pop. 2,197. Taking off early on a Friday afternoon: most every vehicle equipped with a gun rack and towing a boat. Let’s go shoot us some fish in a barrel! Wing us a walleye! Pick off a perch!

Schraube Reservoir’s coming up on our right. Can’t see much of it, thanks to all the cars and trucks and RVs pulling into the exit lane. Speeding up as if to reach it soonest, grasping for that silver glimmer. Could there be a lady in the lake? Has she got a lovely face? Is she stretched at full length with every ripple of skin and sinew delineated punctiliously?...

Prized could be one of the panels in the Screen of Three Doors.

First-done of the twelve. Meaning 8% of the work is already accomplished.

Way to go, Huffman.

Past the reservoir I have Route 65 to myself. It appears to narrow as the open spaces on either side keep widening. Will that crumpled car and sobbing woman pop up again? No, both shoulders stay bare. We remain on our own, unless you count the Black Angus cattle grazing by remote windmills. Ruminating about their bovine fate.

Not so long ago they’d’ve been shipped by rail to Slaughtertown and converted to raw victuals. But no longer in Demortuis: the stockyards there have been emptied, the packing plants shut down, the boom lowered on the Gristly City. Leaving nothing but nox.

The more miles I put between it and me, the easier I’ll breathe.

Twenty-one miles south of Hubsker we turn onto a gravelly road and start doubling back east. 333 shows on the odometer: four more miles to the gate. And no spindly split-rail gate either, but fifteen feet of galvanized steel. Two signs upon it:

![]()

and

![]()

Halt the truck. Get out. Find the right key on Mrs. Wilson’s ring. Unlock the gate, swing it inward. Climb back in (watch your head) and drive on through. Halt again, out again, swing the gate again. Lock it tight. Once more into the truck, to drive the final mile.

Trees reappear. Cottonwoods and other poplars, like on Green Creek Lane. Hackberries, chokecherries, and a single willow with fronds swaying in the breeze.

Four grey walls and four grey towers

Overlook a space of flowers—

Actually just a front yard that never seems to need mowing. Nor are there any towers, unless you count a tall windmill off to one side. But the house does have four walls and they are battleship-colored.

Behold the Old McRale Place.

Frame house with stucco exterior. Solidly built, to withstand big bad wolfwinds. Gables and dormers over a deep front porch. Anachronistic keypad by the homestead doorknob; I tap in the security code provided by Mrs. Wilson.

Open the doors. Prop up the windows. Get some O2 in here. Living room to the right, dining room to the left, front stairs between them leading up to a padlocked impasse: Mr. and Mrs. Wilson’s private quarters. They keep this Place in pretty good shape, considering its distance from Zerfall. Most of the furniture is cumbersome, not lending itself to easy theft. Horsehair davenport in front of the fieldstone fireplace. Taxidermied heads upon the walls: deer, elk, antelope. Heavy oak dining table, heavier buffet. Huge vintage stove and refrigerator in the kitchen, with an antique handpump by the sink. Walk-in pantry, then a mudporch with backstairs down to the cellar.

I lug in my cartons and coolers of provisions. Not intended to last me the entire stay; I’ll have to make a commissary run to Town by-and-by. But for the time being there’s no need to beg or borrow from the neighbors. (Some of whom live so far away that driving to Hubsker would be quicker.)

Next I bring in my portable workbench and clamp-vise, toolbox and portfolio and bundled panels. These are set up in the dining room, which gets north light. Gatherin’ Stormin’, Frieze-Frame, A Perfect Fit and Plue Velvet go on the living room mantel. I didn’t pack the VCR or DVD player, and the Wilsons don’t have a satellite dish out here. But I’ve got the boombox with plenty of CDs and cassettes, plus a deck of cards for brushing up on my Canfield.

Last to be unloaded is the duffel bag of clothes and toiletries. These are distributed in the bathroom, opposite the kitchen, and the bedroom behind it. Chiffonier, chifforobe, chest of many drawers. Oversized bedstead suitable for a homestead: the sort that generations are conceived in, delivered in, depart for the hereafter in. New mattress, though. I’ve brought my own sheets and blanket and pillow, along with my own booze.

(One thing leads to the others.)

Cargo discharged, I park the pickup in what was once a stable. Nearby are other disused ranch structures—a corncrib, a chicken coop. The outhouse is long gone. As is the barn: it burned down years ago and Cy McRale, they say, was never the same afterward. After he died and his widow Mona got too infirm, the Wilsons sold most of the acreage and converted what was left to this little timeshare on the prairie. Hunting lodge in fall and winter; artist’s retreat in spring and summer.

All mine for the moment.

I took my asthma controller when I arrived, well over an hour ago. More than ready now for suppertime. Plain simple chuckwagon grub—no broccoli. Dare to eat red meat. Heap a can of beef stew over instant rice, wash it down with a pot of coffee. (Decaf, I will admit; followed by dried apricots. Some middle-aged concerns should not be ignored.)

Come sunset, the wind rises and temperatures drop. I go for a stroll around the grounds, feeling balmy and pastoral. Good clean country air: you can get it deep into your lungs. Nothing to disturb the peace and quiet but crickets and tree frogs, and a faraway coyote addressing the dusk.

For the first time in two weeks, I feel able to unwind. Without unraveling.

Back at the house I pour a nightcap, turn off the lamps, take my glass and a massive bentwood rocker onto the front porch. First-night ritual: sit here sipping Wild Turkey, and stare up at the sky. Where the stars are out in force tonight.

Constellations blaze across the wild black yonder. Not another light for five, ten, fifteen miles; nothing to dilute the shining. The bright side of isolation. And surrounded by this I can renew my old motto, my personal credo:

Loneliness is not so bad once you consider the alternatives.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Return to Chapter 8 Proceed to Chapter 10