Chapter 3

The Hand of Rotwang

I was given what’s generally referred to as a “secular humanist” upbringing. Which has spurred my half-sister Cassandra (who was given the same) to send me inspirational literature ranging from Dianetics to the Kabbala.

Our mother—before she ended up in the urn in Cassie’s handbag—worshiped bright lights and action sequences, and so became a movie critic. Long before the days of DVDs she was renting feature films and screening them at home on a Bell & Howell projector that often broke down midreel. My father would then be called in to repair it, which he enjoyed more than the films it projected. (He taught physics and worshiped the scientific method, which I thought meant taking things apart in order to put them back together.)

Each home screening was a memorable big deal. The Girl Next Door and I were allowed to watch providing we kept quiet; which we always did, having found other ways to communicate.

What’s this one about?

There’s supposed to be a robot in it.

I thought you said it was a silent movie.

Yeah. So? Robots don’t have to talk.

Silent movies are from the olden days. Robots are from the future.

(This with the lofty-learnèd air she felt entitled to, being eight months older than me.)

The film du jour was a scratchy print of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, with a ridiculous nickelodeon score. Despite these flaws it left an unforgettable impression—especially that of Rotwang, the mad inventor with rampant gray hair, black metallic hand, and smoldering eyes under beetling brows.

I bet that’s what God looks like.

Oh don’t be stupid.

(The Girl Next Door, though a believer in rationalism, attended parochial school and so disparaged my remark from two standpoints.)

My perception of religion was that you were supposed to enlist in God & Son’s army despite its often bootless track record, since it was bound to march to glory someday. But here was Rotwang putting on an almighty light show, converting his robot into a beautiful girl’s lookalike: one who could wink and strut and do a belly dance. This, I felt, was graspable divinity.

“You kids probably shouldn’t be seeing this,” my mother snickered.

You shouldn’t, anyway, added the Girl Next Door. Who already frowned on my use of the word “underhear” to describe what we were doing.

Anyway: as a kid I was convinced the meek would inherit the earth, having had my face crammed into it (plus the sidewalk and curbstone) by the neighborhood bully, Jerome Gullip. Could a tentative “prayer” to Rotwang get something done—and soon—regarding Jerome?

Evidently yes, thanks to a stolen Vespa scooter and a weighty UPS truck. Soon and gratifyingly gruesome.

So I adopted Rotwang as my crypto-deity, carving his genesis of the False Maria into the panel Artificialities that dominates one side of my studio. Thus Old Beetlebrow watches over me, whether he will or nill. And takes a black metallic hand in shaking up my fortunes, introducing the unbargained-for: let’s see how the little chiseler copes with this—

*

It is a Thursday, the 9th of May. Six mornings in a row I’ve come to work without a notion what to do for Geraldine’s Another One.

Could always finish The Glorious Fourth. But then Geraldine might speculate that The Mute Commute was a fluke, not a restoration of my standing as a marketable sculptor. In spite of Eddie’s recent double-bagging.

One, two, pick up a clue...

At Selfsame I am sifting through special-order requests when a clear cool voice comes gliding into the stockroom: “Mr. Campbell?... Mr. Campbell?...”

Gag is off today, so I send Squat Kid out to see who wants what. And he returns with ALICE—

—or her doppelganger.

For the life of me, I can’t recall what she was wearing on the bus this morning. If it’s Thursday, it must have been lilac—but this lady’s dressed in powder blue. (Why “powder” blue? Talcum is white, gunpowder’s black, sugar is sweet and so are—)

—a powder blue sweater over an ivory blouse; a powder blue skirt over don’t be looking at her legs you moron—

“Mr. Campbell?”

“He’s not here,” says Squat Kid. Leaving her with me, and the cat out of the double-bag. That must be it: she’s come to get me fired for goggling at her on the bus. There in her oversized briefcase she’ll have a restraining order to prevent the sale of The Mute Commute, plus a lien on any proceeds therefrom—

“Mister...?” she murmurs.

“Huffman,” I manage. Making a nominal attempt to step down from my stool: a gentleman stands when a lady enters the room. Stands tall when she’s as fine and fair as this one. Unless the gentleman’s feet might fail him now—

“Can I help you?” I say, lifting a stack of papers from a nearby chair. Nearly whisking her powder blue backside as I try to brush off the seat: its, not hers. She decides to keep standing.

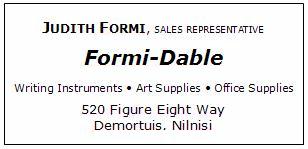

“I’m looking for a buyer. My card—”

Judith?? Can’t be. Even if the Nodder’s name isn’t really Alice, it ought not to be “Judith,” which brings to mind the pigtailed harridan from Leave It to Beaver.

Formi-Dable’s a local firm, whose products Gag banished from Selfsame a few years back. Our contribution to the unfortunate streak they’ve been riding for quite awhile now. A much-publicized new plant failed to materialize; then a chance to become a conglomerate’s subsidiary fell through. Bad decisions, bad timing, bad luck—and diminishing quality, which Gag gave as our reason for discontinuing F-D. Though that actually stemmed from a kickback-quarrel with their sales rep, Murray Burgher—

—whose toupee I see poking round the corner. Aha: using pretty young lady-bait to regain favor. And if Gag’s away, target me instead. Clever move, Murray. Except that of all the fine fair dames on all the buses in all the world, you had to pick this one to twang into my bull’s eye.

He beams like a stage parent as “Judith” launches into her sale routine. Sounding a trifle unsure of herself, like a magician’s assistant obliged to perform the act alone.

“Excuse me,” I tell her. Deepening her uncertainty, till she finds I’m staring down Murray Burgher. Who gives us a salute and withdraws—probably to go knock over a competitor’s display. (As Vashti has brusked, Mannay nuph buttered ohs. Or, demilitarized: “That man ain’t nothing but a turd with toes.”)

His absence must be a relief for “Judith,” who gives me a smile. Yes, by damn! That twin-tiny-ladder-climb! The middle of each lip rises/lowers while the sides stay slightly parted—even her smile is diamond-shaped. And check out her hand as she presents F-D’s latest catalog—there’s the ring with the rock. It must be her.

Showing no sign that she recognizes me.

(Of course, she’s never seen me indoors or without a hat before.)

Her eyes are a classic midnight blue. Like the smile, they are horizontal rhombi set in the vertical rhombus of her face. Seen straight on, the nose is a downward-pointing arrow. Twanging toward her ivory neckline? (Stop that—stand guard—pay attention to what she’s saying.)

“—can produce very broad strokes on any smooth surface—”

And what’s this? A perfume I haven’t encountered since the Eighties. What was it called? “White Linen.” Vicki used to douse herself with it. Bighaired and smallhearted, the Friendly Ghost’s receptionist, pervading the waiting room. On Judith it’s a light airy scent.

“—and this is our latest product, the Oasis brush marker. Fast-drying ink when you put it on paper, but the tip stays moist even if you leave the cap off—”

Baloney Oasis, Stormin’ would say. Still: Judith sounds like a harp as she goes on about the seventy-two odor-free colors, including a full range of grays and earth shades—

The sample marker in her hand suddenly snaps apart.

For an instant she looks perplexed. Then comes a trace of hollow-socketing, and there goes any doubt that here indeed stands Alice. Sits Alice, as I touch her sweatered elbow and direct her into the nearby chair. With her free hand she smooths her skirt down over her knees—no, not over: it is springtime, hems are higher, knees stay primly but pleasantly visible. I hold a wastebasket for her to dispose of the broken Oasis, and a box of tissues for her to wipe her hands. Which are unstained but clammy-looking. She swabs them with a rattle of bangle bracelets crowding both wrists.

“Thank you,” she says. “See? It didn’t leak. They really are good markers.” Hectic little laugh. “Um—please don’t tell Mr. Burgher.”

Not only will I not snitch, but I place an order for a small Oasis selection. Cautioning her this doesn’t mean the complete Formi-Dable catalog will be reintroduced at Selfsame.

“I believe I can change your mind about that, Mr. Huffman,” Judith responds. Extending one hand for me to take and clasp: it is cool and unclammy. Fast-drying, perhaps.

“You,” I inform her. “Not Murray.”

“All righty then,” she says, packing up her briefcase. Another smile bestowed and she departs, I intently watching her go—and turn, and glance back at me, before she disappears.

Oh, by damn. I’m in for it now.

“Judith Formi.” Could she be the daughter of the firm? With that opalescent skintone? Maybe the Formis hail from northern Italy: Venice, Turin, Milan. But her finger also wore a gold band; must be a daughter-in-law. Unless she’s retaining her maiden name for professional purposes. Either way, I still bet her husband’s a wastrel.

How do I explain the Formi-Dable order to Gag? Say it wasn’t given to Burgher but a pretty lady rep—and so whet Gag’s appetite? Achieving Murray’s aim in spite of myself?

More pressingly: do I take the 4:42 this afternoon? Give her a chance to connect Selfsame Huffman with the Goggling Busman? Then that double-bagged cat will leap out for sure—followed by the lien, the restraining order, the slap across my chops.

No. I’ll funk it. For the time being. Catch the 3:12, get home early, try to make something out of that backward glance. Need to put it into a ladderable context. Maybe the Waking Lady bids the Bus of Fools farewell? To become a Breaking Lady—of samples, the ice, our hearts? So we haul the False Maria back to Rotwang’s lab, wanting to exchange her for the backward-glancing Bona Fide—whom Old Beetlebrow, of course, wants to keep for himself.

Robot women. However precisely you calculate their capacities and applicabilities, they add up in the end to mighty cold comfort. With hearts two sizes too small, like bighaired Vicki in Chicago.

I don’t fetish around with wooden simulacra. No problem letting my finished pieces go, be sold to others. Just keep a few exceptions to prove the rule: Artificialities of course, and Gatherin’ Stormin’ as a threshold marker, and Plue Velvet because Pluanne beseeched me not to part with it, and Frieze-Frame and A Perfect Fit...

...because I can lapse into sentimentality like any other sap.

*

Next morning I prepare to face the music. The meow, as it were, of that debagged cat. Taking along my Waning Gibbous zipper portfolio, big enough to carry an inch-thick bubblewrapped 18x24 panel. Plus my security gouge in a discreet cover pouch. No telling to what extent I might have to defend myself, before this day is through.

Hike up Green Creek Lane to Mesher Road and the Park ‘n’ Ride. Wait for the #104 for at least the three thousandth time. Here it comes. Get in line. Take a breath. Mount the steps. Turn and look—

—and she’s not there.

It is to laugh.

All the tension, suspense, absurdly pounding pulse—and then that cross-aisle seat is occupied by a corpulent dropoff. I scan the other rows, down to the yakkety claque: nada. No Nodder. She might have cottoned onto the truth with that backward glance, and opted to avoid me in future.

Is that a pang I feel?

Is it of—relief?

Friday. A sparse commute. Meager day at Selfsame too; few calls or deliveries. Catch up on paperwork. Mull over consequences. Am I being spared an aftermath, or denied closure? “Denied?” Who was blathering yesterday about letting finished pieces go?

Got to maintain the edge. First rule of thumb for a sculptor: always keep your tools razor-sharp. (Second rule: never test them with your thumb.)

So this afternoon I loiter around town for a couple of hours, chillin’ in the GC. Watching traffic pass on The Trail. Lugging my portfolio all the way down Augustus Street, then all the way up Julius.

But you know I think she was shady.

In the sense of a shady rest, that is. Forget about your cares, it is time to relax—on the 4:42. Which is punctual for once. Up 14th Street we chug. And pause. And chug. And pause. Taking on more passengers at each stop. They leave the sideways settee to me and my Waning Gibbous.

Till we reach Figure Eight Way.

Where my

ghoulish neck cranes as we halt. As the door whuffs open. As in she comes. As

her eyes catch mine. Face breaking ice, hearts, on through to the other side—

—into a diamondy smile.

I shift my portfolio off the settee, down behind my legs, and she settles her graceful self alongside me. Easy as that.

“It is you, isn’t it?” she asks.

I incline my head noncommittally.

An empty casserole rests upon her lap. Sharing space with the tote and purse and a light greeny-blue sweater over one arm. She used to wear violet on Fridays; this is “teal,” a color I’ve always found suspect because there was no teal Crayola when I was a kid. Above a teal skirt is a blouse of white ruffles: not too shabby for Casual Friday. Above the ruffles she is translucent: a pearly-peach complexion, bright and clear.

“I was running a little late this morning. Had to finish my casserole for the office potluck. Did you look for me?”

Did she ask me that? Or was it Do you make art too?, with a nod at my Waning Gibbous?

Here goes nothing. Reach down. Unzip the portfolio. Extract an 8x10 glossy and present it to the lady. Whose head stops in mid-nod.

Inhalation. Long, deep, and swelling. (Ruffles have ridges.) Then:

“Ohhhh...” she breathes. “You did this?... Is it—me?”

“I hope you don’t mind.”

“But how...?”

“I studied you from afar. As they say.”

Blink—blink. “Well... I don’t know what to think.”

“About the sculpture?”

“No, it’s beautiful. Where is it? Do you have it?”

“It’s at the Crouching Gallery, Jackdaw Square. In the process of being sold.”

Her midnight blues fly up, flash over: very much the Young Empress. “Well, I would’ve appreciated a chance to buy it!”

Now—maintain your edge. Worse comes to worst, throw yourself on the security gouge and die dramatically at her teal-shod feet. No, in her teal-covered lap: with a smile on your face. (Or, with your luck, an empty casserole.)

“My dealer’s price was rather high.”

“How—?”

“Four figures.”

And there we have it: full-blown hollowing round her sockets.

“No fooling? Well I guess I couldn’t’ve, then...”

“But,” I say hastily, “I’d like to do others. With your permission. I wanted to ask you before. But was afraid you’d say no. And then—evaporate on me, or something.”

“Um... more like this?”

“All sorts. Relief panels, in-the-rounds, I carve many kinds of wood—here are some slides and a viewer if you’d care to” (shut up shut up already) “see cherry and walnut and basswood and mahogany and” (i’m getting out the gouge i swear) “that’s apple pear oak to a lesser extent and this” (what are you doing put that away) “was an experiment in ebony—”

“Ohhhh...” she goes again. Then, reading the caption: “Lubaba in a Gym Suit.”

Actually that one isn’t risqué: my hand is wiser than my brain or tongue. “Lubaba” was my designation for Pluanne’s body wearing LaQuita’s head—at Pluanne’s insistence. Only in Plue Velvet does she wear her own.

“Oops,” says Judith.

“What?”

“‘H. Huffman.’”

“Yes?”

“I forgot to ask your first name yesterday. What does the ‘H.’ stand for?”

“The eighth letter of the alphabet.”

Routine answer to the old, old question. Judith’s expression goes from oops to oh really? with a ladylike moue.

Then a clatter of glass lid on her lap casserole. Thunka thunkity thunk and we are on the Zerfall offramp.

“My stop,” I say.

“Ohhhh!” goes Judith, this time distressedly. “Um—would you like some ice cream?” I almost expect her to produce a full cone from her tote but she adds, “There’s a place I go. In Knotts.”

I stay on the bus. Soon we are back on the Interstate, heading north toward ice cream. “Perhaps you’ll allow me to treat you?”

“Well, I guess you can afford it,” says Judith, handing over my slides and viewer after a last peek at Lubaba. “These sculptures of yours, they’re at a gallery downtown?”

“Some.”

“I’d love to see them for real. I mean, the real ones. Do you sell a lot?”

“My dealer sells them—sometimes. Two this year, so far. Enough to keep me working at Selfsame.”

“Oh. But you said four figures—”

“My dealer keeps 50% of that. Gives me my half a few weeks afterward.”

“Oh,” she says. Holding the glossy of The Mute Commute: “May I keep this?”

“Be my guest.”

She puts it carefully into her shoulderbag. “If I—oh, we’re here.”

We stand together and realize simultaneously that Judith, in her teal heels, is at least three inches taller than me. Unnoticed at the store, due to my ungentlemanly seatkeeping.

“Oh,” she goes once more. Quietly. One of those, I begin to assume—but then she makes an apologetic face, as though embarrassed at being “so tall.” With her sweater off, I can see for the first time how long-waisted she is; her height wasn’t so obvious before, since she doesn’t have Tall Chick thighbones. In fact (I will later discover) her legs are disproportionately short for a five-foot-niner. It’s her torso that’s elongated, and her arms, so that sleeves seldom meet her wrists and she compensates with bracelets.

“Can I take your—” I say, indicating the casserole.

“Thanks, I’ve got it. Don’t forget your—” nodding at my portfolio. Which I was on the verge of leaving behind.

I follow her off the bus and into the Knotts Park ‘n’ Ride, as if we did this every Friday. Her teal skirt zips up the back, describing an upside-down question mark. Or the outer edge of a very well-balanced pendulum.

“Oh gee!” she says, stopping short. “This isn’t going to make it hard for you, is it? To get home, I mean? Is your car in Zerfall?... You walk to Green Creek Lane? Oh good, that’s not far, I can drive you there. I don’t mind short drives on regular streets. I just can’t stand freeways, especially at rush hour. That’s why I like taking the bus... Oh look, my car’s telling you hello.”

Smiling at the H on an aqua Honda Civic. In whose trunk we load most of her baggage and my portfolio. I take the shotgun seat; she gets behind the wheel with lissome ease. Key in ignition, radio comes on: a “smooth jazz” station. Bit too homogenized for my taste, but acceptable; Judith turns it down but not off.

“I always indulge myself on Fridays,” she says, “and only on Fridays. Then I work out extra hard on Saturdays, to make up for it.”

This going for ice cream—is she being professionally friendly? It’s a deplorable practice when the vendor pays, much abused by bribing Burghers and bought-off Gags. Good thing I offered to treat.

I ask about her job. She responds readily. New to field work, doesn’t think she’ll like it much, prefers being an inside sales rep providing customer service over the phone, but needs to bolster her résumé. “Between you and me, they’re sort of treading water.” If Formi-Dable goes under, Judith will be left with less-than-watertight references, yet she doesn’t feel ready to abandon ship. Which is why she’s willing to work with scurvy Murray and get some field experience, hoping F-D will stay afloat long enough for Judith to earn her sea legs and some commissions.

(Deft at keeping her metaphors unmixed, at least.)

“Sales isn’t really my line, anyway.”

“But the family business...?”

“In-law,” says Judith. Coolly.

Aha. Presume she’d rather be a seafarer. Can picture her piloting a sailboat. Be a challenge to carve, though, all that spume and windflap. Or maybe not: she drives the Honda rather slowly, permitting other cars to pull ahead of us. Especially on Mesher Road, which in Zerfall is given over to decaying stripmalls. Up here in Knotts it clings to homespun simplicity, complete with a Malt Shoppe straight out of Pleasantville. Near it Judith parallel parks with an extremity of care; I’m asked to get out and check our space between bumpers, fore and aft.

The Malt Shoppe is not crowded, despite the Friday afternoon. People come in, buy ice cream in assorted modes, take it outside to eat or drink. Judith chooses a peach smoothie —no surprise there—and I order a butterscotch shake, mumbling “Hold the butter.” We take a corner booth and she addresses herself to the smoothie straw, hollowing her cheeks. Then draws another long deep swell of a breath.

“Good?”

“Very. How’s your shake?”

Cold and glutinous. “Makes a nice change. You live in Knotts?”

“Oh yes.” (Smoothie straw. Pat of lips with napkin.) “I don’t eat out much, though. Feels so awkward, being in a restaurant by myself.” (Straw again. Long silent slurp.) “I mean this is okay, ice cream on Fridays. It’s just...” (Straw.)

“Not lived here long?”

(Pat of lips.) “I moved up here in January. From Trey Hills.”

“Chic.”

(Half a smile: the upper lip alone.) “Yes. But it was time for me to stand on my own two feet again.” (Straw.)

My turn to nod. Has she divorced Mr. Bluff? Probably not: still wearing his rings. Walked out on the bastard, then? Maybe it’s a trial separation—detaching herself, step by step. From F-D employment as well. Looking for something new.

I take out my Bruynzeel pencil, flip over a Malt Shoppe promo card, and begin to sketch her.

(Splutter straw aside.) “Oh no, my hair! and I’ve been eating ice cream!—”

“This isn’t a camera.”

“—thank goodness! No, not here—”

“Please. Just as you are.”

She adjusts wiry strands of sugar maple, eyes darting left and right. No one gives us any heed. And gradually the Young Empress resurfaces before me.

I’ve memorized enough of her bone structure that I can concentrate on close-up aspects. Small pink heartshaped earrings. Tints adroitly painted round her midnight blues, applied to their twitching lashes. A tiny mark, too minute to qualify as a freckle, upon the tip of her nose. That touch of teeth, showing no peach residue: very white, very straight.

“Excuse my asking,” I say, “but do you sometimes wear a retainer on the bus?”

“Um—”

“Sorry.”

“No, it’s just—I didn’t know if I could talk, while you’re... um, no: it’s what they call a ‘night guard,’ I kind of clench my teeth when I sleep, even just a nap, and my dentist says without a night guard I’d grind them down to nothing...”

A sketch in every sense of the word. Yet it apprehends her essence with minimal squiggles and smudges. As with Stormin’, as with the best of them, the Dutch charcoal takes to her like lotion on a sunbather. Rendering her elegance, her refinement, in crumbly porous carbon on the back of a cardboard booth promo.

I pivot it for her to see.

And again we get that ocular indentation. Like twisting a spigot: do X, and her sockets hollow; do Y, and they replenish.

She takes the card from me, stares down at it, clears her throat.

“I guess you’re not kidding.”

“About—?”

“When you say you make art. And you did it so fast. I would give anything if... if I could see this... when I look in a mirror.”

“Like I said, I would very much like to sculpt you. Properly.”

Her expression reverts to oh really? Tossing that hair she was so worried about a second ago. “I suppose you expect me to pose all bare for you.”

“Never—”

“—what??—”

“—any way that would make you uncomfortable.”

“Oh.”

“You’ll only sit well if you feel at ease.”

“Oh. I guess that makes sense...”

“And at the standard modeling rate, of course,” I add. (Having learned long ago not to use words like “pay” or “money,” till the prospect herself utters them.)

Judith has gone as pink as her earrings. “I think I have a good face,” she blurts. “When I was in college they asked me to do a little modeling—of clothes, on a runway—but I wasn’t very photogenic. I mean they all said I looked fine, ‘like a cover girl’—you just couldn’t tell from the pictures. They made me look as if I were sort of, well, glazed—but I’m not really like that. Except in pictures. Am I making any sense?”

“Of course. But I don’t use cameras.”

“What about all those slides and things?”

“The gallery provides those.”

Her eyes look into mine. Then back down at the promo-sketch. “Aitch?”

“Yes?”

“You forgot to sign this.”

I print cover lady (after eating ice cream) on the card, plus my H. Huffman hieroglyph.

“Thank you,” she murmurs. “I’ll have to find just the right frame for it. Oh! How can I keep it from—?”

“Needs fixative. Any in your sample case?”

“It’s at work. It’s not really mine, I just borrow it for field calls. So how—?”

The sketch gets slid painstakingly between the pages of a Swimming World magazine in Judith’s tote bag, and we head on out. Where I’m lost in wonder at the sight of her lilting athletic gait. Yes, a swimmer: that would account for the sturdy shapely legs, the limber stride, the upright carriage and high firm curvature. Maybe there’s a bathing suit under that business outfit; glistening spandex concealed by teal. If we were to go to the riverside, lose the shoes and skirt and ruffly blouse, set her gazing out o’er the Ipsissima as if to find a boat beneath a willow left afloat—

—we could outfrenchlieutenant John Fowles and Alfred Lord Tennyson.

As she starts the car I ask what her line really is, if not sales.

“Je voudrais enseigner le français.”

“‘I would like’... something French?”

“To teach it. I’m a total Francophile.”

She got her bachelor’s degree in education and wants to go back to school, earn her master’s, teach French on a secondary level, maybe coach the girls’s swim team on the side. Just as soon as she can afford the tuition. Hence her field sales and hope for commissions—if Formi-Dable doesn’t go belly-up too soon.

“Um... how much is the standard modeling rate?” she wants to know.

“Fifty an hour.”

“Dollars? For real?”

“With contracts, releases, receipts.”

“Gosh! Well then. If I did model for you—”

“—comfortably—”

“—‘comfortably’—would other people be there? Could I, um, bring my roommate?”

“Sure. Why not?”

(Roommate! Didn’t she say she didn’t mind being on her own?)

The smooth jazz station starts playing Sarah McLachlan’s “Possession,” and “Oh I love this song!” cries Judith. Turning it up, humming along with the soaring chorus: I’ll take your breath away...

Either she hasn’t heard this was inspired by an obsessed stalker, or she’s yanking my chain a little.

I would grant her that privilege.

But keep an eye peeled for traps and snares.

We turn onto Green Creek Lane. All the branches on all the trees are in bloom and I find it an agreeable vista. But Judith, as I direct her into the Wilsons’s gravel drive, appears to be getting unnerved. “Oh,” she says in a tight voice around a dry swallow, “is this where you live?”

For crying out loud, it’s an ordinary three-truck garage—not some terrorist’s lair or portal to Hell. No model-bodies are buried beneath the ash trees (that I’m aware of).

“Yes. That’s my studio up there. It’s artier inside.”

Pop goes the trunk latch. I take that as my cue to get out, retrieve my portfolio, express enjoyment of the ice cream and our opportunity to chat.

“It was fun,” says Judith. “And, um, about the—I’m not promising anything—need to think it over—but will let you know.”

From the Waning Gibbous I pluck a Crouching Gallery flyer. Scribble my number on a corner, hand it in through the car window. Do I ask for hers in return? Not yet. Beware of prematurity. She nods at the flyer, smiles out at me, gives a little wave and drives off. Sitting very straight and oh so by damn lovely.

*

That night I scour the bathroom, anticipating what the future might hold. Containing the urge to hone and strop every chisel in the toolrack. Even if a session does take place, what are the odds it could pan out as well as the first one with Stormin’, or Josephine, or—

Miranda Parales. Who merengue’d her way through Selfsame one remarkable summer, almost a decade ago. Still living at home, freshly graduated from high school, now attending a Barbizon be-a-model-or-just-look-like-one factory. Confident that wealth, fame, and sophistication would all soon be hers. Which might have been more credible had she not looked like a cartoon gatita, all frisk and pounce and scamper.

When I trained Miranda on handling merchandise her attention never wandered, since it was wholly devoted to the half-dozen soap operas she videotaped by day, caught up on at night, and could prattle about by the hour. If I did manage to get her thinking about art supplies, she would declaim “We’re all out of foamboard!!” or “I can’t find any more gesso!!” as though it meant the family hacienda was threatened with foreclosure.

Big Gag stopped by to scope out Miranda from bottom to top (his idea of supervision) and warn her to “Watch out for this one—he’ll try to sculpt ya.”

That was all she needed to hear. Ohmygaw! Was it true? Did I really make statues of people? How soon would I want her to pose for me? Why hadn’t we got started yet? Wasn’t I ever going to ask her? (Pout, stomp, flounce.)

As with any gatita, the impulse was to dangle the yarn just out of tantalized reach. For a week I scratched my chin and went “Hmmm...” while Miranda steamed and fumed and hissed. What! Did I find something wrong with her face or her bod, that I didn’t think them worthy of sculpting? Or was it that she acted too giddy, too skittish, when I knew she would try her very very best to do exactly what I wanted. (Batting moist brown eyes the color of just-oiled butternut.)

On Saturday I borrowed a truck from Mr. Wilson, drove down to Selfsame, and told Miranda her hour had come. She jumped and clapped and grabbed her backpack, not bothering to time out. No one saw her leave, or scramble into the pickup, or take off with me. Only when we hit the Interstate did she think to ask where I was taking her.

“To my studio.”

“Where’s that?”

“In Zerfall.”

“Where’s that?”

Cellphones were not yet prevalent and Miranda didn’t have one. Her expression turned anxious, then dismayed, then woeful. By the time I parked (unseen) in the Wilson garage, she seemed petrified—except for her Princess Jasmine T-shirt, which was all aflutter.

No resistance to my taking her hand. Or tugging her out of the truck. Or in and up the stairs, Miranda moving like a sleepwalker and making not a sound. All alone with me in my home, her whereabouts unknown.

I don’t think I’m more carnivorous than the next man.

But it did have a powerful effect on my imagination.

Put her in an open doorway, standing aghast at what she sees (the viewer). Or down upon her knees, bending aghast over some shattered object that had been her heart’s delight. Or huddling naked in the shower stall under a stark cold drizzle, transfixed by the ghastly feeling she’s being watched—

—as we maintain the edge—

—but contain the urge.

My lips an inch from her ear as I said, “Drink?”

“Wha-a-a-at?”

“Looks like you could use a drink. Pour you some wine?”

She leaped back against the nearest wall, clutching it with outspread arms and tragic gasp. To this day I don’t know whether Miranda was genuinely frightened or engaged in bosom-heaving melodrama. Now he’s trying to drug me so he can take me and have me! O, how can I avoid such a fate? O, how might I effect my escape?

“Oh no thanks not really thirsty wow forgot to let my mom know where I am mind if I use your phone—” Frantic dialing. “¡Yoly! ¿Dónde está Mamacita?... AIEEE!! what are you doing??”

This last wailed into my face as she caught me quickdrawing hers.

I showed her the sketchpad, on which I had exaggerated her prettiness till it outshone even Jasmine’s cartoon allure.

Over the phone: “Randa? Randa!”

“Call you later,” she told Yoly.

Hanging up to fling herself around in glamour-style stances. Which she couldn’t or wouldn’t hold long enough for me to do anything with, even when I pushed her into a chair and told her to just sit still. Fresh pouts and flounces: why had I practically kidnapped her if I found her so hopeless, so unbearable? Why wasn’t I taking pictures of her, like these—

—producing from her backpack assorted Barbizonery. Most of which had already been thrust under my nose over the past week. But here was one I hadn’t seen before: a spectacular rear view of Miranda in mosquito-net negligée and rubber-band thong, soulfully regarding her frontal charms in a full-length mirror.

“Ohmygaw...”

“My sister took that in our bedroom,” said Miranda, pouring herself some wine. “Nice, hunh? You can’t see the flash in the mirror or anything.”

This bodacious image I replicated on a kiln-dried butternut panel: El Espejo de Miranda. It popped the eyes of most everyone who saw it. I received commissions for a dozen duplicates, making it my most lucrative piece then and still. The financial side got very complicated and bilingual, with Geraldine and Miranda’s Mamacita haggling over compensation for Yoly as the source’s photographer, and a bonus for Miranda who turned it into a ticket to L.A. Last I heard, she was appearing in a Spanish-language soap opera on Univision. Good for her.

So that escapade turned out well for the both of us. My imagination has run riot on similar occasions, not always as fortunately. Once even involving a shower stall—

—never mind.

Dream instead of Miranda tonight. Despite my having gotten jaded on her sweet young tetas y nalgas, by carving them over and over again. Like gorging nonstop on caramel flan.

(Not a thing you should do just before going to bed.)

Lights out. Hit the hay. Count shavings to get to sleep. One, two, pare with a view. Three, four, shear it some more...

(Kiln-dried to kill the bugs. Never told her that. Butternut’s often infested, full of wormholes. Left by butterfly larvae? Heaving and fluttering?...)

Just as I drift off, Rotwang jostles my memory.

With a newspaper squib from a couple years ago: Formi-Dable heir killed.

Took note of it then as a minor happenstance. Another example of F-D’s bad luck. Can’t recall how the guy died, except that it was in an accident of some kind.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Return to Chapter 2 Proceed to Chapter 4